Both Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will and Sergei Eisenstein’s October are propaganda films of the highest caliber, both in content and execution. While Riefenstahl focuses on the exploitation of National Socialist imagery, Eisenstein focuses on the recreation of a pivotal stage in the Soviet class struggle.

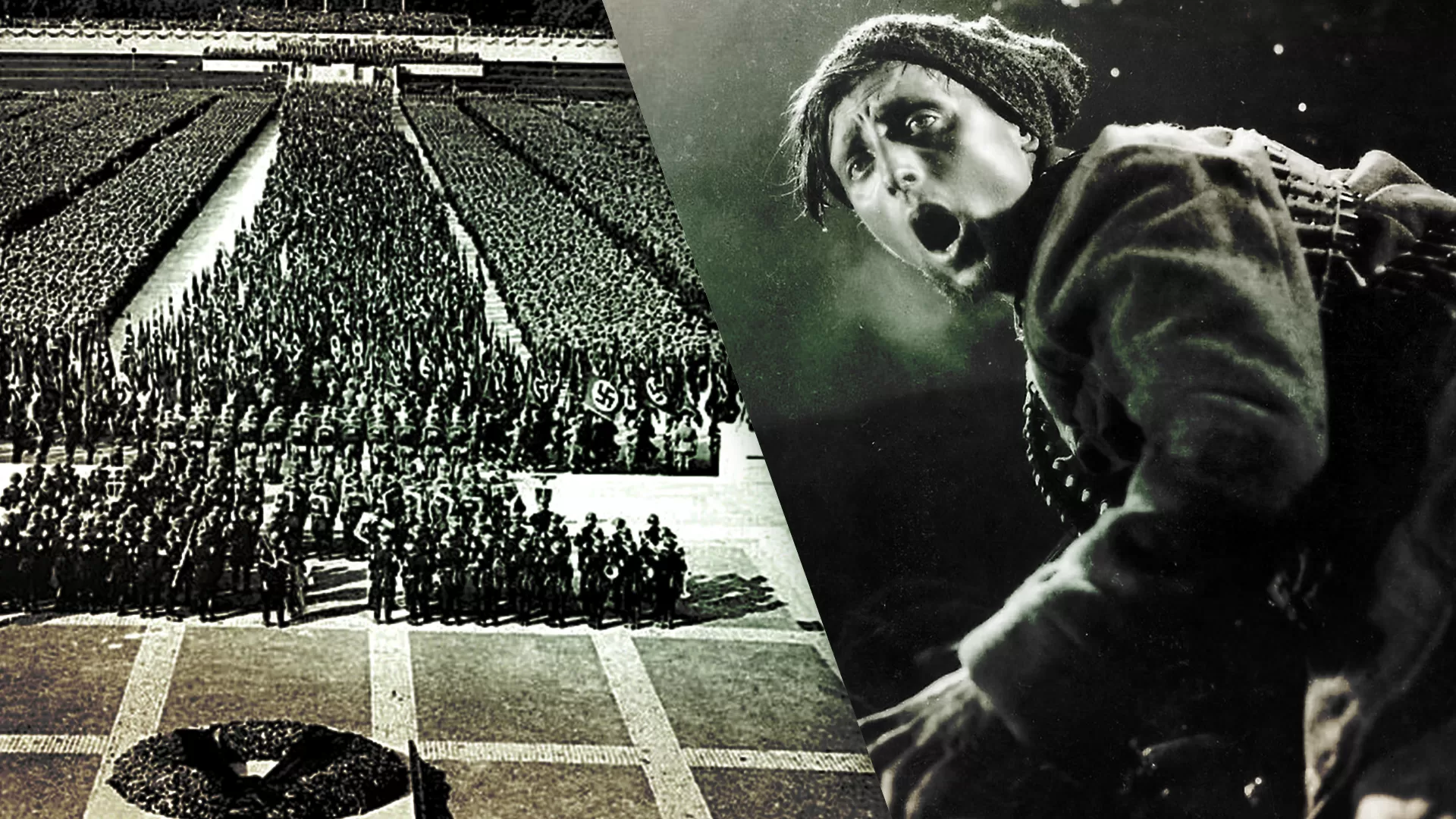

Both films succeed in trying to manipulate the audience’s political Weltanschauung by employing various innovative cinematic techniques, such as bold editing and mesmerizing images that linger seemingly forever on the screen (e.g., the endless National Socialist parades in Triumph of the Will). However, one must understand that National Socialism and Communism were almost diametrically opposed on the political spectrum. While National Socialism tried to focus on the betterment of the Nordic race, Communism tried to encompass all of humanity.

Richard Taylor argues that almost no film exists of the October Revolution. The Soviets were able to use this fact to their advantage. They established “a basis of historical legitimacy for their regime and the absence of adequate documentary evidence gave Soviet film makers a golden opportunity for the re-creation of the realities of Russian history, and for some improvement on them.” (Taylor 93) This, of course, means that the Soviets did nothing more than glorify the construction of their Bolshevist state. They were able to do so because they had total control of the media.

By employing such a famous director as Eisenstein, they gave themselves double credit; one for Stalin having such a creative genius on board, second for Eisenstein (the great artist that he was) being able to transcend mere dramatization of the event. As V. Pudovkin argues, “The Soviet artist…must feel that his creation is constantly dependent on the needs and interests of the people….” (Pudovkin 51) This is to say that the artist should cater to the needs of the people to be fooled into believing that they truly live in a worker’s paradise. Of course, Eisenstein was well aware of that intention when he shot October, as is evident when one views its sheer stylized form and content.

It seems quite apparent that while October is “a symbol for the artist’s unison with his time” (Zorkaya 69), the film is also deceptive because it does not represent what was actually transpiring during the October Revolution. On the contrary, the film is a mere representation of the fact. By dedicating itself solely to the tenth anniversary of the Revolution, October reduces its significance to that of a mere spectacle for workers and peasants to celebrate. It is addressed to the Russian peasantry and what it supposedly gained from the Revolution. But it is fair to assume that this is the trick behind the film since, in reality, the peasantry was the last group to gain anything from the Revolution. This makes October nothing more than a big lie.

On the other hand, when comparing October with Triumph of the Will, it becomes clear that the latter is the superior of the two films. Triumph of the Will is not a recreation of actual events but a documentary (albeit a rather propagandistic one) of the events themselves. Adolf Hitler himself commissioned Leni Riefenstahl to make a documentary about the Party Rally in Nuremberg (1934).

According to Robert Gardner (who interviewed Riefenstahl), she was at first reluctant to make the film because “she knew nothing about the Party or its organization.” (Hull 74) Riefenstahl also insisted that the film should be financed by her rather than the Party. All the circumstances mentioned above are good indicators that Triumph of the Will is at least less propagandistic than October.

It is probably true that Triumph of the Will is the most impressive (and probably the most effective) propaganda film ever made. According to Siegfried Kracauer, “Leni Riefenstahl made a film that not only illustrates the Convention to the full, but succeeds in disclosing its whole significance. The cameras incessantly scan faces, uniforms, arms and again faces, and each of these close-ups offers evidence of the thoroughness with which the metamorphosis of reality was achieved.” (Kracauer 301)

Riefenstahl certainly showed what the Party Rally was about – pomp and splendor – a big show-off for the masses. But this was the reality of the spectacle itself. It can thereby be deduced that Riefenstahl did nothing more than record the bombastic atmosphere around her. She did not have to embellish it or make anything up through exaggeration, as Eisenstein certainly did in October. The reason that Riefenstahl was not “forced” to fictionalize her account of National Socialist glory was the fact that she was in the middle of it and not in a recreation (like Eisenstein when he propagated Communist glory). While October is a non-faithful adaptation of a historical event, Triumph of the Will could be viewed as a simple recording of history.

Richard Taylor states that Triumph of the Will is “at the same time …a superb example of documentary cinema art – and a masterpiece of film propaganda.” (Taylor 177) This statement sums up the diverging opinions of the film. While most critics are pressed to view it as nothing but a piece of shameless propaganda, some argue that the film holds value as a documentary per se. The fact that it does not have any voice-over commentaries and no scenes staged specifically for the film should prove that the only propaganda one can get out of it stems from its content. But it should be noted that Riefenstahl did not create the content as she was merely recording it. That is why Triumph of the Will is subtitled “The Document of the Reich Party Rally 1934.”

According to Taylor, Leni Riefenstahl claimed in an interview that “[e]verything (in Triumph of the Will) is real. And there is no tendentious commentary for the simple reason that the film has no commentary at all. It is history. A purely historical film.” (Taylor 189) This is certainly not true of October. Bizarrely enough, according to Taylor, “the very absence of documentary material (on the October Revolution)…has…meant that subsequent historians and film makers have turned to October as their source material, and Eisenstein’s fictional recreation of reality has…acquired the legitimacy of documentary footage.” (Taylor 93) This is ironic indeed, considering that Triumph of the Will is infamous for being a vicious propaganda film while, we now learn, October has acquired the status of “source material.” One cannot help but wonder if it should not be the other way around, considering the circumstances under which both films were made.

Bibliography

Hull, David Stewart. Film in the Third Reich. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1969.

Kracauer, Siegfried. From Caligari to Hitler. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1974.

Pudovkin, V. Soviet Films: Principal Stages of Development. Bombay: People’s Publishing House, 1950.

Taylor, Richard. Film Propaganda: Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1979.

Zorkaya, Neya. The Illustrated History of the Soviet Cinema. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1989.