Much has been written about the animated film The Lion King, highlighting its reactionary essence and conservative values. However, it appears that it has not yet been examined through the lens of Traditionalist doctrine. We have made a humble effort to bridge this gap and direct the viewer’s attention to certain aspects of The Lion King that align with Traditionalist notions of political power and social harmony.

It is hard to dispute that Disney’s The Lion King has become one of the most significant cultural phenomena of the 1990s. Over the past two decades, millions of viewers worldwide have watched it, and generations continue to enjoy it as a family. The film’s characters are instantly recognisable. Interestingly, the ideas within the movie do not stem from modernity but rather from ancient cultural and value systems. One could even say that The Lion King serves as an introduction to Traditionalism for young viewers. The film’s imagery and plot align well with the early chapters of Julius Evola’s book Revolt Against the Modern World, in which the influential thinker explores the meaning and symbols of royal power in long-lost eras through legends, tales, myths, and treatises.

Examining The Lion King from this perspective makes the 2019 remake’s release even more astonishing, given that popular culture trends have become increasingly hostile to values typically associated with right-wing worldviews since the original film’s debut. Many of these themes, prominently featured in The Lion King with a positive connotation, are undoubtedly part of that worldview.

Let us take a closer look at the storyline of the iconic animated movie and identify the symbols and meanings within it that resonate with the principles of Traditionalism.

Anointed by the sun

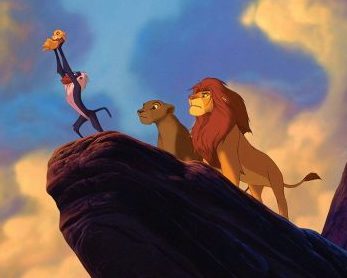

The film opens with the story of Mufasa, a wise lion king who rules over the savannah. The lion is often considered a solar symbol in various cultures, and solar symbolism is associated with royalty, as seen in Egyptian, Iranian, Roman, and other traditions. This connection is also evident in the use of lions in the heraldry of aristocratic and royal families. As the film begins, the sun rises, and all the animals in the savannah pay their respects to Mufasa’s heir, Simba. The shaman Rafiki conducts a ‘solar anointing’ ritual, highlighting the otherworldly nature of royal authority and its ties to the transcendent solar principle. Rafiki cracks open a vibrant red fruit, representing the celestial body, and anoints Simba’s head with its juice before lifting the young heir towards the rising sun.

Additionally, the film explores the concepts of royal authority, the cycle of life, and the king’s responsibility. Mufasa shows Simba their kingdom from a rock that overlooks the entire pride’s territory, symbolising the throne as the world’s center. This imagery echoes the end of Plato’s dialogue Critias, where Zeus convenes with the gods in his royal residence, which offers a simultaneous view of all things in existence. This immovable point signifies the state’s steadfastness and connection to the timeless, emphasising the intermediary position of royal power between heaven and earth. Mufasa tells Simba that everything the sun touches is part of the kingdom, suggesting that these lands are under the protection and influence of royal power. Conversely, the shadowy elephant graveyard inhabited by hyenas exists outside the kingdom’s borders, representing the twilight realm.

The forces of chaos and degeneration

The hyenas, representing chaotic forces, invade the kingdom’s territory, only to be repelled by the lions. Royal power, therefore, is a barrier against chaos, one of its primary functions. Mufasa likens a king’s life to the sun’s journey from sunrise to sunset, followed by the rise of the next king-successor. He emphasises that being a king is not about self-indulgence but maintaining the natural balance and life cycle, ensuring everyone has his place in the hierarchy. Evola suggests that the cyclical sense of time and sacred understanding of space are characteristic of the world of Tradition. Mufasa also points out the starry sky, noting that ancient kings live eternally, watching over earthly actions, a concept that resonates with legends of kings who retreat to other realms but remain ready to return.

Simultaneously, Mufasa’s brother Scar, representing the dark, telluric side and driven by a selfish thirst for power, conspires with chaotic forces (hyenas) and treacherously murders the rightful king. He embodies tyranny, where power becomes an end in itself. During his reign, the valley experiences imbalance, the natural hierarchy collapses, and drought, famine, and other disasters ensue.

Hakuna Matata – a philosophy promoting thoughtless consumption and self-centredness

While in exile, Simba is influenced by the Epicurean, nihilistic, and irresponsible philosophy of Hakuna Matata (Swahili: ‘no worries’) presented by Timon and Pumbaa, dwellers of the bountiful jungle. This philosophy promotes thoughtless consumption and avoidance of any uncomfortable questions about life’s meaning and one’s destiny, reflecting another distortion in the modern world. The animals living in this place are content but purposeless.

At some point, the grown-up Simba experiences an awakening of ancestral memory as he gazes at the starry sky, recalling his father’s words. His friends, however, laugh at his reflections on the great kings of the past. Despite this, the deep-rooted urge to fulfill his higher purpose cannot be suppressed. Simba’s chance encounter with his childhood lioness friend Nala in the jungle reawakens his masculine principle and helps him overcome his self-centredness. Rafiki then reappears to perform an initiation rite, reaffirming Simba’s royal lineage. Simba returns to the Pride Lands, overthrows Scar in a counter-revolutionary coup, and ultimately restores harmony to the valley. Timon and Pumbaa, who previously lacked a higher purpose, happily join Simba as his allies.

Father and son: the king is eternal

The film’s creators, intentionally or not, have effectively conveyed the concept of royal power, its significance and grandeur, in a manner reminiscent of the Traditionalist school of thought, as represented by René Guénon and Julius Evola. Paying attention to these aspects makes re-watching the film even more engaging. The Lion King is a rare and remarkable example in contemporary culture that essentially contradicts it, offering an alternative perspective on power, time, social harmony, and hierarchy that diverges from modern norms. The political ideal in The Lion King bears no resemblance to democratic values or civil society but is perceived as positive and genuinely legitimate. The film presents content that opposes reality, drawing on pre-modern, primordial stories. The popularity of The Lion King demonstrates that these narratives remain relevant to people, despite the distortions of modernity, suggesting that they are indeed of primordial nature.

It is wonderful at least one mainstream cartoon is appropriate for traditionalist and nationalist parents to let their kids enjoy! Great analysis.

I enjoyed the original version at least. I hope the WOKE monsters leave it alone.