Both Plato and Aristotle advocated a form of government in which only the wisest should rule. Whatever the majority of the popular socialist-democratic critics and writers of the caliber of Anatole France and George Bernard Shaw, who are not far removed from their unreflective superiority and modern preconceptions, have said, and continue to say, they are all aristocrats in the inner sense of the word, and therefore aristocrats in the fullest sense of the word, to the exclusion of any geniuses who should be called strictly geniuses. And those geniuses who were geniuses in the strictest sense of the term were, without any exclusion whatsoever, all aristocrats in the inner sense of the word, and therefore had an infinitely deep longing and attachment to tradition and all things traditional, the “home” of the aristocratic spirit in this sense of the word.

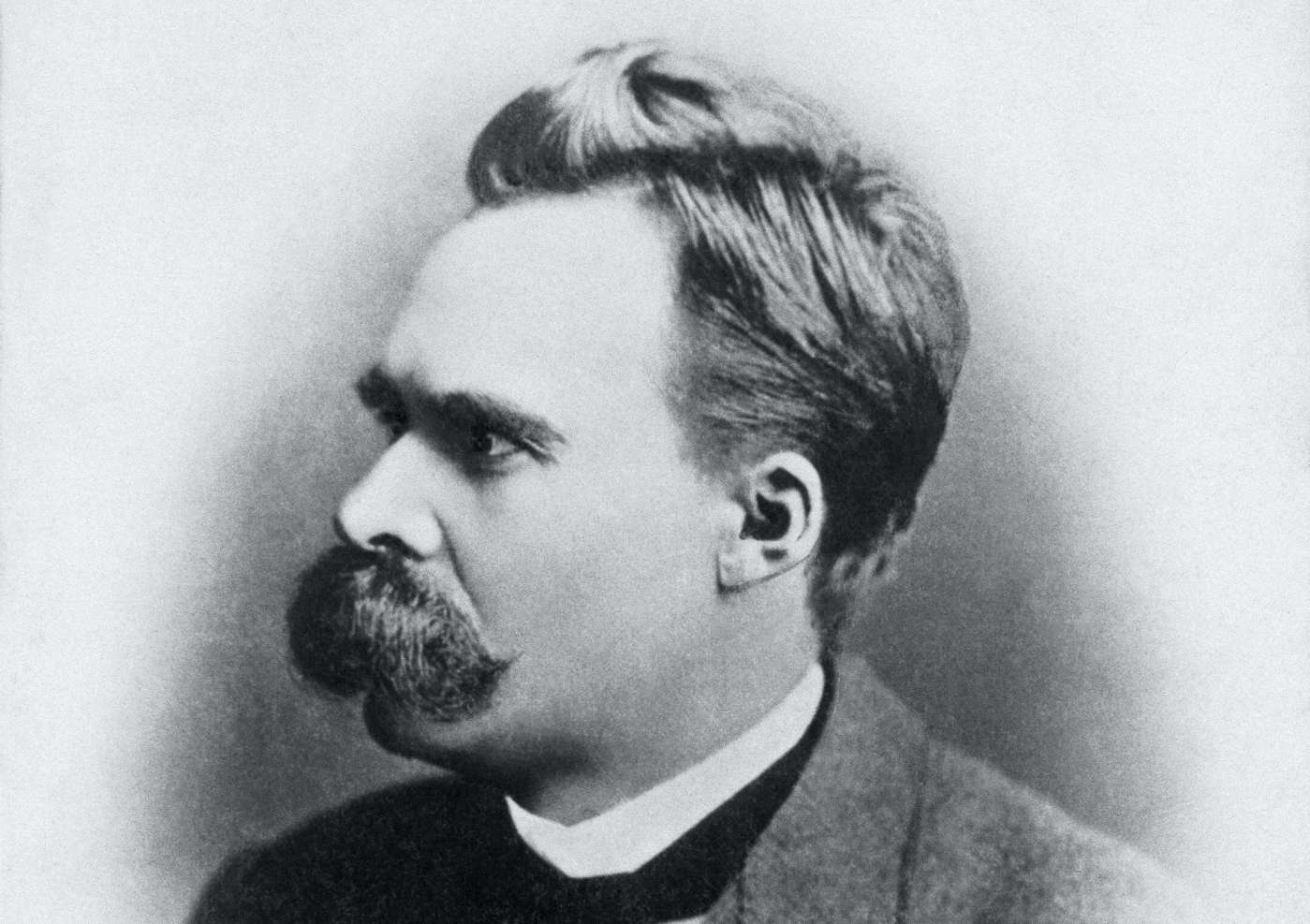

Among them, the one to whom I have a special attachment is Heinrich Heine. In his qualities, which were the most difficult to understand and the most easily misunderstood by his countrymen and contemporaries, and in his marvelous, ultra-Germanic genius, and although he often thought and said that even he himself felt nauseated by Germanism, yet with a real and secret attachment to it, he made a greater contribution to the German people and to the German language than most poets could hope to do. In his fate that he had to learn to speak only as a clown, in the form of self-tricks, from a school of antithetical destiny, Friedrich Nietzsche felt a special and very deep kinship with Heine. Heine, who had such a connection with Friedrich Nietzsche, and who in a sense was a prototype of Nietzsche, probably only saw Japan through very limited material, such as the famous Philipp Franz Balthasar von Siebold’s Japan Magazine, but also through the help of his mysterious genius intuition. Perhaps aided by this poetic intuition, Nietzsche was able to see the essential merits of Japan, which were quite different from the frivolity of the so-called Japanese favoritism in the world. He had an outstanding understanding of and attachment to Japan.

It was not until the late 1880s that Nietzsche lost this healthy awareness, directly from the Japanese intelligentsia, such as Hirobumi Ito and his delegation who went to Japan to prepare the constitution, the many diplomats and students who went before and after them, and even the German intelligentsia, who were already very much aware of Japan. It can be assumed that the German intelligentsia was already well acquainted with Japan and all things Japanese, as Daniel Halévy described in his 1911 biography of Nietzsche.

It is no wonder, therefore, that Nietzsche had a better understanding of Japan than Heine did, but it is also a great pleasure to see Nietzsche’s utterly passionate love and affection for the Japanese spirit, culture, art, and all things Japanese.

In a letter from Nietzsche to his “Llama” (as he called his sister, for her habit at spitting at him when she was angry) on December 20, 1885, yielding to bitterness, he wrote to her. She was spending a last Christmas at Naumburg.

“How stupid it is that I have no one here who might laugh with me! If I were stronger, and if I were richer, I should set up in Japan, to know a little gaiety. At Venice I am happy because there one can live in the Japanese manner without too great difficulty. All the rest of Europe is pessimist and mournful…”

Shortly before the letter was written, Nietzsche had visited his old friend Baron Reinhart von Seydlitz in Munich before leaving Germany. He was shown a rare collection of Japanese art, which aroused such deep interest in him that he could not help but feel envious.

Many have read at least some of the basic foundation of Schopenhauer’s famous The World as Will and Representation, which is based on Buddhist thought. While it must be noted that although the philosophy of Nietzsche appears on the surface to be a continuation of the ancient religious thought of Persia, it is in fact more deeply related to Buddhist thought than that.

However, Schopenhauer died in 1862, and Nietzsche’s sound consciousness was lost in 1896, a gap of over thirty years, during which time there was a remarkable development in Indology in Europe and Rabat, especially when Nietzsche became acquainted with many outstanding Indo-philosophers. The two thinkers’ understanding of Buddhist thought differed in such depth and degree that they could hardly be discussed on the same day.

It is interesting to note, moreover, that these two great thinkers, who at one time had what might be called a master-disciple relationship, present to us one’s lower philosophy in direct proportion to the depth of one’s understanding of their Buddhist thought, and the other’s higher philosophy in direct proportion to the depth of one’s understanding of the other’s philosophy, It is a matter of interest to say, more frankly, that the summit of Buddhist thought as understood by Schopenhauer is, as it were, the last limit of what his philosophy could reach, and that, in contrast, his philosophy could also reach the height that Buddhism, as far as it was understood by Nietzsche, could eventually reach. To add one more thing, it is even more interesting to say that in its most fundamental tendencies, in the end, Schopenhauer was nothing more than a Buddhist in his way of speaking, whereas Nietzsche was nothing more than a Buddhist in his way of thinking.

According to Schopenhauer, however, Kant’s so-called reality, or body, is a blind will called “will to life,” and the development of this blind will, or the product of its development, is that this world is the worst world, and that in this world there is a life to be lived This life, then, must be the worst life.

Therefore, Schopenhauer states, the only way to save oneself from the worst of the world and to be liberated from the worst of life is to destroy or to stop the blind will, the proper “will to life.” But to deny the will to life is to deny the will to artistic enjoyment and to deny the will to religious abstinence.

More precisely, the denial of the will by artistic enjoyment means that artistic intoxication through so-called genius intuition places us, at least for a moment, in a state of indifference, as in Kant’s philosophy, and thus puts our will to life, even if only temporarily, in a state of denial.

Of course, such a negation of the will by art is only temporary, whereas what can truly and permanently negate the will to life is the method of religious abstinence, and there is no other way.

Then, as to how this true denial of the will is achieved, first of all, a thoroughgoing pessimistic outlook on life, which can be called the impermanence of all things, or mono no aware in Japanese, makes one realize the futility of the pursuit of pleasure, and a thoroughgoing pantheistic world outlook, which can be compared to the law of no-self, makes one realize that individual existence, as Kant states, is merely an illusory delusion. But, the next step is to realize that the worldview of theists is not a mere illusionary delusion.

Next, this realization will inevitably lead us to the three precepts: simple food, which means the denial of individual life; chastity, which means the denial of the preservation of the race; and poverty, which means the denial of selfishness.

And finally, these preceptive practices, that is, the unceasing repetition and continuance of abstinence, can finally completely negate the blind will, which is called the will to life.

Thus, the only complete method of liberation of Schopenhauer’s disciplinary practice, which he himself calls abstinence, is more aptly described by us as asceticism. At the very least, it should be seen as having a more ascetic tone than the Buddha’s own Middle Way, or what he called the Eightfold Path, as far as we understand it. In other words, whereas the Buddha had warned against the two views of presence and absence in thought and had advised against the two sides of suffering and pleasure in life, Schopenhauer’s conceptual attitude was to lose the middle way and to be inclined to “nothingness” and negativity, while his preceptive attitude was to be inclined to “suffering” and to do hardship. In other words, in essence, the Buddha is not a Buddha. In short, it is quite different from the Buddha’s own so-called Middle Way attitude.

If, in external relations, those who stand closer to the Buddha but who merely grasp at the mere skeleton of the teachings and fail to perceive and understand their inner, substantial life are the so-called Mahayana, then, on the contrary, those who are able to perceive the Buddha’s non-physical life and the true spirit of his teaching, even if they are far from him in external relations, are the true Mahayana. In other words, those who have gained insight into the true spirit of his teachings, even though they may be more distant from the Buddha in their external relations, are the so-called Mahayana followers. While the first group has a formal understanding of the form of the Buddha’s teachings, the essence somewhat eludes them, they are often considered Mahayana by those impressed with their knowledge. It is the second group, then — those who grasp the essence of the teachings, even if their formal knowledge may be imperfect, are purer in their faith.

In this sense, it cannot be avoided that the Buddhism which was taken by Schopenhauer as the basis of his philosophy was quite deliberately a Lesser Vehicle one.

Nietzsche, who saw the Buddha as a physiologist par excellence and his teaching as nothing short of the most scientifically advanced regimen in the world, found it difficult to say on the same day how much importance the Buddha attached to his fundamental attitude of the Middle Way or Eightfold Path when compared with Schopenhauer and others. In fact, it seems to be more correct and more profoundly understood.

In other words, in this way, Nietzsche could see Mahayana Buddhism as Buddhism just as much as Schopenhauer saw Mahayana Buddhism as Buddhism. The so-called Middle Way or Eightfold Path is a life that is more in accordance with the so-called regimen (here, life and thought in the narrow sense of the word are lumped together under the word “life”) than the daily life of ordinary people in general, compared to the life of suffering or pleasure, and is therefore a life that is strictly more pleasing, and also more true and more beautiful. The true teaching of the Buddha, unlike that of Schopenhauer, sees liberation from this life as devotion to a better life, and that the method of devotion is exactly the same as the artistic life or the effort in art itself.

In this way, then, Schopenhauer, who tried to deny the will to life in contrast to Nietzsche, who again tried to affirm the will to life more forcefully by pushing up the so-called will to power, was, from the right point of view, further away from Nietzsche, and just that much closer to Mahayana Buddhist thought.

Of course, Nietzsche spoke so emphatically in favor of life, and it must be said that Mahayana Buddhism or the Buddha’s teaching seen from a Mahayana perspective, at least insofar as it was Buddhism at all, denied life rather than affirmed it.

Yet Nietzsche, too, often spoke of the superhuman as a lover of the downfall and insisted on the virtues of restraint, self-discipline, tragic living, and the virtue of giving as if sharing the warmth of the sun, as ruler morality against slave morality, and aristocrat morality against lowly people morality. In this respect, however, it can be seen as placing some restrictions on his so-called “affirmation of the great life.”

In contrast, Buddhism does not simply deny life, but first denies it, then denies it again, then denies it a third time, and so on through endless denials. In this way, negation can be said to be a kind of affirmation. Of course, it cannot be a simple and straightforward affirmation, but if we see it as an affirmation based on the negation of negation, which is sustained indefinitely, then it seems as if a mysterious and very elaborate affirmation of life peculiar to Buddhism itself emerges from the depths of the abyss of negation, like a spray of water.

And in this light, it seems to me that my own attitude of so-called negative affirmation or positive negation in Mahayana Buddhism, regardless of the appearance of its expression, is not only not too different from the “great affirmation of life” of Nietzsche and others but is rather quite close to it, when seen from the comparison between essence and essence.

Needless to say, forms of Mahayana Buddhism appeared one after another in the Buddha’s native India in the centuries or even decades after his death. These also entered China in the same order in which they had appeared in India, and in succession, without much delay. However, to put it frankly, these Mahayana Buddhas in India and China existed only as theories, or rather as mere philosophy, as sutras, treatises, exegeses, etc. of scholars who possessed a brilliant religious vocation.

It was not until after their arrival in Japan, more specifically in the Kamakura period, that these mere philosophies became more than philosophies again. When Mahayana Buddhism came to Japan, it did not merely broaden and elevate itself from a philosophy to a religion. The change from mere philosophy to religion was at the same time a great transition in the way it infiltrated all aspects of our Japanese life through religion and art, and into Japanese culture in general.

The originality and genius of the Japanese, by and large, lies not in inventing and devising new so-called theories, art forms, and ideas but rather in spiritualizing what are mere theories and ideas into the true life of life itself and of culture itself. So-called ideas, as long as they are just ideas, are only abstract concepts. If it is an exaggeration to say that the Japanese give birth to things themselves, at least symbolically, instead of concepts, it is at least as hyperbolic to say that the Japanese can symbolize and concretize what other peoples have grown up with only as concepts, and transform them into life itself.

Regardless, the various so-called Eastern ideas can be easily understood and even celebrated by any European, as has already been demonstrated. But when we think of the fact that it is no coincidence that it was only by Europeans like Nietzsche that something so embodied in Japanese life, so symbolic and so uniquely Eastern, was truly understood and cherished, our gratitude to him should be the greatest of all. When I think of the fact that it is no coincidence that something so Eastern could only be truly understood and loved by a man like Nietzsche, I cannot help but feel that gratitude and a sense of good acquaintance with him draws us closer and closer to him once again.

Where is a good place to start studying Mahayana Buddhism?

Unrelated to this wonderful article:

There is too much disinformation about Buddha, an Indo-European certainly. What he probably looked like below.

Disregard statues and drawings of a fat non-Atlantean Buddha please!

Hahahahha, great!

Curious where Chōkōdō Shujin would place Evola’s studies of Buddhism on this kind of spectrum. “The Doctrine of Awakening: The Attainment of Self-Mastery According to the Earliest Buddhist Texts” by Evola is what introduced me to Buddhism. Previously I thought it was liberal pacifist nonsense.

One of the Baron’s best and most overlooked works.

If this is true (and I have no reason to think it isn’t) it is a very powerful ability. This is an extremely intriguing article, thank you to the author!

Too much to love about Japan.