European ‘right-wing’ intellectuals Baron Julius Evola (1898–1974) and Ernst Jünger (1895–1998) are prominent representatives of radical political thought in the twentieth century. Evola and Jünger belonged to the same ideological camp, which we call ‘right-wing’, and their political works belonged to the same epoch. Both were notable political radicals in the 1920s, chose the path of ‘internal emigration’ in the 1930s, refusing to establish relationships with the right-wing radical regimes that came to power in Italy and Germany, and, after the war, detached themselves from politics and focused exclusively on intellectual work.

In this article, we will briefly examine the movement of Julius Evola and Ernst Jünger from active political radicalism to apoliteia, that is, to the establishment of a significant internal distance from contemporary politics, coupled with a refusal to participate actively in it, and try to understand the reasons that led these thinkers to make such a life choice.

Julius Evola, who served in the ranks of the Italian army during the Great War (served as an artillery officer; his unit was located in the Asiago area; did not participate in combat), turned to politics in the mid-1920s and criticised the democratic system (including in the pages of Giuseppe Bottai’s Fascist Critique), the bourgeois elements of fascism, the servility of officials, and the Catholic Church. The political aspirations of the young Evola were associated with the hope for a renaissance of pagan spirituality, the return of the heroic to the everyday, the restoration of a just social hierarchy rooted in spiritual power.

The Italian thinker set out his model in the work Pagan Imperialism (1928), in which he claimed that ‘[t]he West no longer knows wisdom: it does not know the noble silence of those who have overcome themselves, does not know the bright peace of those “who see”, does not know the proud “solar” reality of those in whom the ideas of blood, life, power have been reborn… The West no longer knows the State’.

Formulating an alternative to Catholic spirituality, Evola turns to the Hyperborean myth, the ‘solar Nordic tradition’, praising the era of the ‘Golden Age of Humanity’ spoken of in ancient legends: ‘Already in the most ancient times of prehistory, where positivist superstitions possess ape-like cave dwellers, there existed a single and powerful proto-culture, echoes of which can be heard in everything great that has come down to us from the past – like an eternal, timeless symbol. The Iranians know of airyanem vaejo, a country located in the far North, and see it as the first creation of the “God of Light”, the place from which their race came. It is also the abode of “Radiance” – hvareno – that mystical power which is associated with the Aryan race and, in particular, with its divine monarchs’. Through this lens, Evola looks at both pagan Rome and the medieval Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation.

According to Evola, paganism represents a living and active immanent spirit that affirms true values, and the traditional empire embodies this spirit. Evola believes that restoring an empire like the one Mussolini dreamt of is impossible without the restoration of such spirituality. Just as the soul organises the body, the elite should organise the state. In other words, Evola does not consider the possibility of a ‘revolution from below’ – chaos, disintegration, and degradation can only come from below. Instead, the revolution must be carried out by the elite, leading the nation and guiding it forward, which is the focus of the Baron’s work.

Evola’s elitist restructuring of fascist Italy should take place under the symbol of the ‘return to the imperial eagle’ and primarily address two main issues – overly abstract spirituality and overly materialistic politics. The Italian thinker builds upon the idea of an organic state in which the elite qualitatively and existentially differs from the masses. Consequently, the new elite should play a spiritual role, combining ‘priestly’ and ‘royal’ principles.

In Pagan Imperialism, Evola critiques contemporary notions of ‘nation’ and nationalism. He argues that the nation emerged when the empire, aristocracy, and feudalism perished. Evola sees more sense in the Indian concept of ‘caste’, the highest of which upheld values. Both Indians and Germans aspire to individuality; Evola asserts that collectivism is foreign to them. The concept of nation is collectivist. Tradition entails differences and free relations between personalities. The Italian thinker then calls nationalism a ‘return to totemism’ and Hegel’s idea of ‘the state as the embodiment of the absolute spirit’ a ‘mask for the Leviathan-like idea of the Soviets’.

Baron Evola resolutely critiques both capitalism and socialism. The gradual and consistent fall of aristocrats, feudal lords, and monarchs led to the degradation of the idea of the state to the level of a utilitarian and economic union. Instead of the power of quality, the power of quantity arises – specifically, the quantity of money, a faceless yet powerful force. The crisis of a plutocratic society gives rise to an international proletarian movement, whose victory would mean the complete collapse and disintegration of all living and noble values.

Evola also criticises contemporary reverence for technology. According to the Baron, technical power is fundamentally immoral in nature, and it can empower anyone, making it another mechanism of the ‘world of quantity’. The path of traditional power means ‘to know is to be’, not ‘to know is to have’. Evola is alarmed by the obsession with conquest and creation, characteristic of the ‘Faustian’ man. This is essentially a form of messianism, stemming from the inadequacy of the soul and contradicting traditional harmony. According to Evola, this is the ‘human’ aspect that Nietzsche urged to overcome.

The Baron calls upon his contemporaries for spiritual courage, without which a decisive step towards the opposite of European decline – a step towards a new harmony and newly regained totality of existence – is impossible. He asserts that ‘there exists a perfect, total, positive system of values, developed taking into account other forms that have entered modern profane civilisation, which is a sufficient basis for readiness to negate – without fearing to come to nothing – everything belonging to European decline.’

Radicalism, which can only be characteristic of youth and passionate, sincere belief in the truth of one’s convictions, is the most accurate description of this early work by Julius Evola. He tried to set a vector for Italian fascism (and in a broader sense – for all of Europe) towards the restoration of ancient traditions, of which only fragments and fragmentary memories remained in the mass consciousness. In Italy, this book clearly did not go unnoticed, but it did not achieve the effect desired by the author. Hansen notes that Antonio Gramsci, the imprisoned leader of the Italian communists, took notice of Evola’s work. Mussolini read Pagan Imperialism, but apparently political common sense prevailed, and in 1929 the Lateran Pacts were signed, marking the revival of the alliance between the Italian government and the Catholic Church. This was a blow to the hopes of the young Baron – there was no longer any talk of a pagan revival in Italy.

Soon after the closure of the journal La Torre (The Tower), founded by Evola in 1930, the Baron abandoned attempts at direct political influence and devoted most of his time to working on the fundamental work Revolt Against the Modern World, which was published in 1934. This work, written under the evident influence of Guénon, from whom Evola borrows the approach, and Spengler, from whom Evola largely borrows the method, radically juxtaposes two spiritual poles – the ‘world of Tradition’ and the ‘modern world’. The Baron fully embraces and substantiates the traditional view that historical progress is absurd, and that only gradual and relentless degradation of spiritual, social, and political forms takes place in reality.

In Revolt Against the Modern World, there is no trace of the fiery political call of Pagan Imperialism. From the perspective of assessing the contemporary political situation, it is an utterly pessimistic work, offering a disheartening diagnosis of the modern world, while also outlining a normative ideal – the semi-mythical ‘world of Tradition’, organic, harmonious and imbued with immanent spirituality. Modern man has lost contact with the ‘transcendent’, forgotten this knowledge and does not strive to regain it. So, in this case, how can the ‘revolt’ against the modern world look if no traditional restoration is possible? It is exclusively a rebellion of the spirit, of an existential nature rather than political (in the broad sense), which only a small minority capable of perceiving the ‘spark of Tradition’ can undertake. Evola’s later work will be addressed to these people.

Revolt is the first major work by Evola based on the principle of apoliteia. All pure forms described by the Baron in the first part of the work, having normative value, are essentially unrealisable in the conditions of the modern world, as the thinker himself acknowledges. In conclusion, Evola states: ‘Those who have already been forced to admit what they call “the decline of the West”, due to the testimony of facts, usually accompany their considerations with various appeals aimed at erecting protective structures or provoking some reaction. We do not want to deceive ourselves or others; leaving consolation to cheap optimism, we only desire an objective perception of reality.’ He does not call for heroic but hopeless political struggle – according to the Baron, ‘the West can only be saved by a return to the traditional spirit in the context of a new, united European consciousness’, for which there were no conditions at the time. We can add that at present, in the first quarter of the twenty-first century, Europe has moved even further away from positive traditional ideals – widespread materialism, mockery of everything sacred, a lack of understanding of any healthy hierarchies, and new varieties of the liberal-democratic myth (such as social justice warriors and similar distortions) are the norm. Thus, for those who do not spiritually belong to the modern world, only the path of individual salvation, far from politics in the broad sense – the path of apoliteia – remains. Evola’s later works focus on clarifying specific aspects of this path for the few who are worthy of attention – he calls them ‘aristocrats of the spirit’.

Despite the already formed inclination towards apoliteia, during World War Two, the Italian thinker made one last attempt to exert effective influence on the political process. In the small work Synthesis of the Doctrine of Race (1941), in contrast to the pro-Nazi biological racist model introduced in Italy in 1938, he proposed the concept of a ‘race of the spirit’, as far removed from materialistic eugenics as possible. However, this attempt also ended in failure, after which Evola finally withdrew from politics.

The short article ‘Orientations’, written by Evola in 1950, can be considered a manifesto of traditionalist apoliteia. The Baron points out that the problem of raising a new person capable of changing the current situation has come to the fore, as any idea without a worthy bearer is doomed to disappear. The model for Evola is the ‘spirit of the legionnaire’, who realises the illusory nature of modern myths and achieves self-realisation thanks to his exceptional qualities.

Inside, such a person creates an order that is not subject to the ‘world of rebellion’. The ideal of the ‘special person’ is not related to either economic or social classes. This is a style of ‘active impersonality’; the criterion is action, responsibility, task execution, and goal achievement. ‘Our true homeland is in the idea. It unites not land or language but a common idea. This is the basis, the starting point’, the Baron firmly states. Both secular and clerical states are alien to Evola – the spirituality professed by the new type of person does not need dogmatic settings, moralism, or puritanism. Evola’s call is as follows: ‘This idea must win, first and foremost, in the image of the new person; a person ready to resist; a person who has withstood among the ruins. If we are destined to overcome this period of crisis and unstable, illusory order, only such a person has a future. But even if the fate of this world is predetermined and its final destruction is imminent, we must stand firm: under any circumstances, what we can do will be done because our homeland cannot be captured or destroyed by any enemy.’

This call was interpreted by some young Italians as a call for radical actions (including violent ones), which was fundamentally wrong. Therefore, in subsequent works – primarily in the books Men Among the Ruins (1953) and Ride the Tiger (1961), – Evola developed the idea that resistance to the modern world must have, first and foremost, an internal, spiritual character, especially in the absence of any external, political support. The most critical task facing the ‘special type of person’ – the ‘aristocrat of the spirit’ – is to preserve himself in a totally hostile environment, to survive in conditions when no institution, regime, or culture existing in the modern world can support him sufficiently. Hence, the appropriateness of apoliteia as a path to survival and self-preservation, to the acquisition of genuine meanings beyond the state and political. Only when building the necessary unshakable existential mode of being within oneself, will the ‘special person’ have the opportunity to claim the future and attempt to ‘ride the tiger’ – to tame the unleashed demon of modernity, which should be his ultimate goal. This is the trajectory of Julius Evola’s thought evolution concerning the issue at hand.

Now let us turn to the life and creative path of the second hero of this article – Ernst Jünger. Despite the fact that he, like Evola, belongs to the ‘right-wing’ flank of radical political thought (idealistic, anti-materialistic, elitist, and aimed at the organic), Jünger belongs to a different intellectual tradition, which is often defined as ‘conservative-revolutionary’ or as ‘reactionary-modernist’. From this follows a similar ‘enemy image’ to Evola’s (the ‘leftist’ and the ‘bourgeois’) but a distinct positive ideal during the early radical period of thought.

Unlike Evola, Jünger spent the years of the Great War at the front line, demonstrating remarkable heroism. He was wounded fourteen times, receiving a through-and-through head wound and a through-and-through chest wound. In January 1917, Jünger was awarded the Iron Cross, in November of the same year – the Knight’s Cross of the Order of the House of Hohenzollern, and in September 1918, he became a knight of the highest military award of the German Empire – the Order Pour le Mérite. During the war years, Jünger kept a diary, which was published two years after the defeat under the title In Storms of Steel (1920). This book made Jünger famous; he became an iconic figure – a front-line soldier wrapped in glory, who discovered his talent as a writer and gradually became one of the most prominent German intellectuals of the first half of the twentieth century. He served in the Reichswehr until 1923, but soon after the failure of the Beer Hall Putsch, he retired.

In the 1920s, Jünger held one of the leading positions among German radical right-wing intellectuals – the so-called ‘conservative revolutionaries’. Based on his own combat experience, the thinker puts forward the ideal of frontline brotherhood and in his numerous political publications, he celebrates the frontline soldiers who should form the backbone of the nationalist revolution in Weimar Germany. The revolution of the front-line soldiers, these ‘symbols of courage, honour, and bravery’, should lead to the creation of the state of the future, the contours of which are already clearly perceptible: ‘It will be national. It will be social. It will be armed. Its structure will be authoritarian… It will be the modern nationalist state.’ If the ultimate goal of the nationalist revolution is clear, how can one define the ideals it should serve?

First and foremost, Jünger insists on the necessity of spiritual renewal in Germany, the liberation of the German spirit from the chains of materialism – both liberal and Marxist. ‘Representatives of the most vulgar materialism, stock market speculators, businessmen, and usurers – that’s who’s in favour now! Everything revolves only around goods, money, and profit’, Jünger writes in 1923 in the Völkische Beobachter. Capitalist elites must give way to people of a new type – the frontline soldiers: ‘The figure of the solitary fighter, the man in the steel helmet, the unknown warrior who bore the heaviest burden on his shoulders, must become the ideal, the guiding star of the movement.’ The frontline soldier has inherited the spirit of the Kaiser’s army, within which everyone performs their duty at their own post. In him lives the understanding of duty, and he is devoted to the common cause.

The high existential qualities of the frontline soldier are conditioned by the experience of war, which, according to Jünger, was a logical consequence of an era ‘which worshipped matter, substance, as God’. In this was a sign of fate – to show the inner emptiness of the era of materialism. The soldier heroically overcame the hardships of war through the strength of his spirit. A person must pass through matter, subjugate the material, and establish his domination over it – this is the lesson of war that Jünger sees.

Secondly, the German thinker insists on the primacy of the nationalist idea, which is constantly present in his articles – if not as the main theme, then as the general spiritual background. Jünger rejects the ‘universal’ in favour of the ‘particular’. Nationalism sets its own standard, which it draws from the spirit of the nation. ‘Nationalism does not wish to reconcile itself with the domination of the masses, but demands the domination of the personality, whose superiority is created by the inner content and living energy. It does not desire equality, nor abstract justice, nor freedom reduced to empty claims. It wants to indulge in happiness, and happiness consists in being oneself, not another. Modern nationalism does not wish to float in the airless space of theories, does not strive for “free thinking”, but wants to find firm connections, order, and root itself in society, blood, and soil’, Jünger writes in the foreword to his younger brother Friedrich Georg’s book The March of Nationalism (1926).

Thirdly, Jünger contrasts a uniquely conceived irrational with the ideals of the Enlightenment, as evidenced by the concept of will, which is present in his political journalism. The German intellectual presents himself as a staunch opponent of the Enlightenment tradition, denying the idea of progress that leads to looking down on the past. For him, rational knowledge is just a fragment of general knowledge, which should be combined with the latter, but in no case should it replace it entirely. Irrational faith in the positive power of higher spheres of the spirit, embodied through will, is extremely important for Jünger: ‘Faith in a hidden meaning fills us, the hardened generation, born in the scorching womb of trenches and proud of our past. And although this past is associated with failure, we must not conclude from this that it was meaningless, as one can hear from every trader on the corner. What men die for can never be meaningless.’ The question one must ask oneself, according to Jünger, is what one must do, not what will succeed. Fate acts in his worldview as the source and cause of this necessity. Through will and character, all one’s strength should be directed towards achieving the necessary – that which ‘fate wants’. Will sets in motion the hands that show the time of fate on the clock of epochs.

Unlike Evola, Jünger welcomes the advent of the age of technology. Of course, in his view, the primary focus is on the human being – the one who controls technology. In modern warfare, the spiritual and the material go hand in hand, without one of these components victory in confrontation is impossible. The machine is an instrument. ‘Indeed, the machine has taken away much from us. It has made our life more energetic, but also deprived it of brilliance. Depriving us of the whole, it has turned us into specialists’, Jünger writes in the article ‘The Machine’. But blaming technology itself is a mistake. ‘The intellect creates the instrument, and the will of the blood directs and applies it’, claims the German writer. The spirit should not oppose technology; it should control it. From the understanding of necessity, which is determined by fate, Jünger derives the idea that the man of modernity, the man who allies with technology, represents a new masculine type – the aviator, the military pilot is spiritually akin to the sailors of the past; he has the same courage, the same fearlessness in the face of the elemental, the same will to dominate. It should be noted that similar motifs are present in Evola’s work. For instance, in the article ‘Seafaring as a Heroic Symbol’ (1933), the Italian thinker suggests that the seafarer is ‘identical to the hero and the devoted, a person who, leaving behind ordinary “life”, strives for something “greater than life”, in terms of a state of overcoming decline and passions’. He uses different instruments, but instruments are merely a form of expression of life.

In the 1930s, Jünger develops his political ideas, transforming the figure of the frontline soldier into the image of the worker, who becomes the second of the four ‘great types’ in his work. In 1932, the German intellectual presents his vision in the book The Worker: Dominion and Form. The key concept of Jünger’s theory is Gestalt; by this, he means a whole that includes something greater than the sum of its parts. A person is greater than the sum of atoms, a family is greater than the union of a man and a woman, and a nation is greater than the sum of citizens living in the same territory. All human history is a struggle of Gestalts. Jünger claims that ‘man, as a Gestalt, belongs to eternity’.

The Gestalt of the worker is defined by the German intellectual in contrast to the image of the bourgeois, a typical representative of the ‘third estate’. According to the writer’s views, the German has never been a good bourgeois, being insufficiently ‘civilised’. The German has never truly believed in the ideals of the ‘third estate’, which are too cheap and human.

Jünger’s worker is not a representative of the ‘fourth estate’ nor an economic class, as in Marx, but a new existential type of person. The worker goes beyond bourgeois concepts and does not accept conformism. The bourgeois strives for security. The worker, on the contrary, embraces the elemental. The warrior, the hunter, the believer, the seafarer – these are ‘worker’ figures. The worker lives dangerously, but he is not a romantic. He is not prone to idealisation, which, according to Jünger’s conviction, always gradually degenerates into nihilism.

Continuing the theme of technology, the German intellectual asserts that it has its own symbolism – behind the processes it is involved in, there is an irreconcilable struggle between Gestalts. The Gestalt of the worker decisively puts technology at its service, striving for dominion over matter. When total mobilisation is complete, technology will also reach its completion, elevating humanity to a different level of organisation.

This organisation should be the worker state, replacing liberal democracies. The principles of the worker state are nationalism and socialism. Freedom is the force that mobilises the Gestalt of the worker to implement this project. It is not an end in itself. National democracies are a mixture of routine, cynicism, and scepticism, which do not inspire trust among the people. This entire spectacle corresponds to the categories of ‘moral’ and ‘reasonable’, so beloved by the bourgeois. ‘It is an atmosphere of a swamp, which can only be cleansed by an explosion’, Jünger is convinced. In his opinion, worker democracy is much closer to an absolute state than to a liberal democracy. The new-style parties, aiming to build such a state, rely on elite selection and training, rather than mass participation. The ‘new aristocracy’, born in the trenches and imbued with the Gestalt of the worker, must create a new organic structure of a special type. Bourgeois orders are constantly under attack, and sooner or later they will fall.

The Worker draws a line under Jünger’s period of creative work marked by political radicalism. This text was highly appreciated by Julius Evola – in his commentary on The Worker, he wrote that ‘the polemical direction of the book against economic materialism, the ideals of prosperity of the “herd animal”, the bourgeoisification even of those circles that dress in the uniform of opponents of the bourgeoisie, is complemented by a constructive striving for the affirmation – even if sometimes expressed in an unacceptable tone – of the necessity of education aimed at preparing a new type of person, more inclined to give than to ask, to overcome the crisis engulfing the modern world’.

Jünger’s radicalism of the 1920s and 1930s appealed to Evola even in the post-war years, despite significant differences in the political ideals proclaimed by these two thinkers. On November 17, 1953, Evola sent a letter to Jünger, informing him of his admiration for the early period of his creative work. The Italian intellectual offers his services as a translator of The Worker into Italian, noting that this work could have an ‘awakening effect’ on contemporary society. The problem Evola faced in 1953, prompting him to contact Jünger personally, was that finding the original edition of The Worker was not possible at that time, and Evola did not know who to turn to for translation rights, so he addressed all these questions to Jünger personally, hoping that he could count on his assistance in obtaining or purchasing a copy of The Worker and approving an Italian translation of the book.

In his response to Julius Evola on 21 November 1953, Ernst Jünger informed him that he had not yet decided in what form The Worker should be republished, indicating that a revision of the text might be required. Instead of revisiting this early work, the German thinker suggested that Evola consider his new political treatises, namely Across the Line, The Forest Passage, and The Gordian Knot. The correspondence between the two thinkers ended at this point – Evola did not reply to Jünger’s letter but heeded his recommendation and wrote a review of The Gordian Knot, which was published in the East and West journal in July 1954.

In this review, Evola pays tribute to Jünger’s early works, written in the spirit of ‘heroic realism’, the source of which is the author’s direct heroic frontline experience. At the same time, the Italian traditionalist notes that ‘unfortunately, Jünger’s later works, despite a less pronounced inclination towards “pure literature” and stylistics, demonstrate a significant decrease in intensity from the point of view of the German writer’s perception of the world’. In particular, in the work The Gordian Knot, in which Jünger examines the relations between the East and the West within the framework of historical time from the Greco-Persian wars to the twentieth century, the German writer, according to Evola, focuses on issues of politics and ethics, neglecting the religious and spiritual element. The historical oppositions that Jünger employs are often incorrect from Evola’s point of view – for example, Jünger’s desire to oppose the ‘freedom’ of the West to the ‘despotism’ of the East was found completely absurd by the Italian thinker, demonstrating its inconsistency with examples from Hindu and Zoroastrian mythology. According to Evola, Jünger, when discussing the East, concentrates on semi-wild and barbaric forms (such as Hun or Mongolian nomads), not paying due attention to the higher cultures of this region. Jünger’s desire to present the West as a ‘world of freedom’ is criticised by Evola on the basis of relatively recent examples of Bonapartism and ‘popular dictatorships’, which the Italian thinker contrasts with the significantly more organic understanding of the authority of higher power in traditional China and Japan for traditional worldviews.

Examples of heroic, unconditional self-sacrifice, which Jünger also considers typologically ‘Eastern’, Evola regards as manifestations of the heroic spirit inherent in the Kshatriya elements of all civilisations, and cites examples from Roman and modern European history.

In conclusion of the review, Evola once again points to the significantly more important early stage of the German writer’s work: ‘To prevent a spiritual catastrophe, modern man must open himself to “Being in the highest sense”, develop himself – and it is precisely in this respect that Jünger’s slogan of striving for “heroic realism” converges in meaning with the ideal of the “absolute individual”, capable of measuring himself against the highest standard of primal elements, capable of extracting the highest meaning even from the most destructive experience in which his own individuality practically plays no role – an individual accustomed to the most extreme temperatures, finding on the other side of them the “zero point of all values”.’ In Jünger’s early work, according to Evola, he maintained this highest level of existential tension and metaphysical sense of life. The later work of the German writer, on the contrary, according to the Italian thinker, represents a retreat from the positions already taken and therefore has significantly less value.

In the post-war years, both Evola and Jünger moved away from political radicalism. In the latter’s work, a certain ‘demarcation line’ can be considered the work On the Marble Cliffs (1939), in which the figure of the partisan, representing a striving for ‘internal emigration’ and freedom hidden in the heart of the forest, replaces the worker. This type evolves into the figure of the ‘forest traveller’ in the post-war years, appearing in the work The Forest Passage (1951), and can be seen as the development of the partisan in a spiritual sense. Further on, in the novel Eumeswil (1977), another ‘grand type’ – the anarch – emerges, no longer needing the ‘forest’ to preserve himself and his freedom. As Alain de Benoist notes, the anarch is content with ‘vertical alienation’ from power; he has crossed the ‘wall of time’ and ended up on the other side of history, without breaking with the world.

In turn, we can note that the anarch occupies a more passive position in relation to the contemporary world than Evola’s late ‘exceptional man’, who must precisely tame the tiger of the modern world; in other words, while being in the world (moreover, at those points where its tension reaches its peak), he must not only ‘preserve himself’ but also be active on that ‘front’ to which he is destined.

So what prompted Evola and Jünger to move from positions of political radicalism to apoliteia? Both had already completely abandoned active attempts to exert direct influence on politics by the end of the 1930s. One of the reasons may be that the political reality of those years either did not provide opportunities for the implementation of their projects, or their attempts to execute them were not entirely correct.

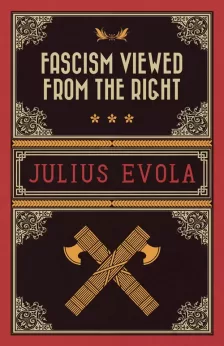

In the case of Evola, the situation unfolded as follows. The Lateran agreements, concluded by Mussolini with the Catholics, consolidated the conservative status quo that had emerged in the early years of the regime. The genuinely revolutionary component of Italian fascism in the 1930s was minimised, and fascist state-building increasingly approached ‘bourgeois’ models (Evola analyses this in detail in his work Fascism Viewed from the Right (1964). In Germany, Evola was well known – in the second half of the 1930s, he often appeared in the country, giving lectures at various events. His most significant activity took place between 10 December 1937 and 27 June 1938. However, as evidenced by SS reports, the official authorities did not particularly welcome Evola’s performances and even subsequently banned his public activity in Germany. In post-war Italy, the thinker involuntarily gained a reputation as a guru of neo-fascists, but he himself had no interest in politics, not joining any movement and not recommending such a not too thoughtful activity in the new ‘liberal’ era to anyone who needed his advice.

The situation with Jünger developed in a similar way. In the early stages of the National Socialist movement in Germany, the German thinker collaborated with the NSDAP press (in particular, he was published in the Völkischer Beobachter), but the closer Hitler came to his goal, the more Jünger became disillusioned with National Socialism. After the National Socialists condemned the terrorist acts of the Landvolk, it became clear that Hitler intended to come to power through parliamentary means. This was not to Jünger’s liking, as he held more radical views. He also detested the vulgar biological racism of the National Socialists. Gradually, he distanced himself from the NSDAP. As early as 1927, Jünger called the National Socialists ‘sectarians who conjure up race’. At the same time, he refused the mandate of a Reichstag deputy from the NSDAP, ironically noting: ‘It is much more honourable to write one decent line than to represent sixty thousand blockheads in the Reichstag.’ At the end of 1933, Ernst Jünger left Berlin, going into ‘inner emigration’ and refusing to become a member of the National Socialist Academy of Arts.

During World War Two, Jünger did not participate in combat. For most of the war, he held the rank of captain and served in a staff position in Paris. In 1944, his son Ernst was killed in the war on the territory of Northern Tuscany controlled by the Italian Social Republic. During the war years, the German thinker wrote the work Peace: A Word to the Youth of Europe and the Youth of the World, in which he pointed out that the seeds of war were ‘thin seeds, sown too abundantly, and their very traces must be eradicated. Genuine fruits can grow only from universal human kindness, from the best core of man, his most noble, selfless depths.’ In the post-war years, Jünger’s works were banned from publication for four years, but the ban was later lifted. The German thinker retired to the town of Wilflingen, where he lived until the end of his long life, focusing on literary creation and not participating in politics.

Thus, as early as the 1930s, Jünger was aware of the fundamental disagreements between the future he envisioned and the path chosen by Germany in the form of the NSDAP. Like Evola, he was not willing to compromise. He spent most of World War Two in the role of an observer rather than an active participant. Having experienced the death of his son and reconsidering a number of fundamental issues, which he wrote about in Peace, he finally abandoned politics and focused on other matters – questions of technology, the future, history, individual freedom, which he addressed in his post-war novels and essays. Unlike Evola, who remained loyal to the traditionalist model throughout his life, Jünger underwent a much more noticeable evolution of views, as a result of which he renounced the radical nationalism he adhered to in his youth, but he did not develop another political ideal that he could defend in the public sphere with equal passion. This is also one of the reasons for Ernst Jünger’s apolitical stance in the period following the end of World War Two.

Concluding the article, we should note that the evolution of views is a rather natural process that any major thinker encounters, one way or another. Often, a change in position leads to a change in attitude towards certain phenomena and events, a change in the model of behaviour in the public sphere and political space, as evidenced by the cases of Julius Evola and Ernst Jünger that we have briefly discussed. These changes are the result of the unrelenting work of creative thought throughout one’s entire life, paying attention to the changing circumstances of the surrounding world against the backdrop of timeless values. We believe that this is one of the reasons why the works of Evola and Jünger continue to be of living interest to us in light of all the crisis events we face in our problematic modernity.

Excellent summary of the intellectual lives of two of the most towering giants of the 20th century. The author clearly compares these two thinkers and points out their similarities but more importantly their differences.