“Anyone who has common sense will remember that the bewilderments of the eyes are of two kinds, and arise from two causes, either from coming out of the light or from going into the light…” – Plato, The Republic

“The only thing you can’t do is to deny that you’re in an impossible situation. That act of imagination is to deny the conditions you’re in; that’s hope.” – Kathy Acker, Blood and Guts in High School

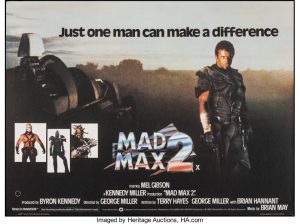

In the twisted landscape of George Miller’s The Road Warrior, there thrives a connection eerily resonant with the ruminations of Friedrich Nietzsche. As Nietzsche pens with somber wisdom, “He who fights with monsters should be careful lest he thereby become a monster.” The protagonist of our tale, Max Rockatansky, embodies this alarming thought, traversing a monstrous world while dealing with his metamorphosis.

Beneath the morbid vestige of The Road Warrior, a world stripped bare of civilization’s comfort unveils itself. Nietzsche’s gloomy adage, “That which does not kill us, makes us stronger,” rings true in this vision. Our haunted hero, Max, is a monument to this strength. Once a champion of the law, now a nomad in a wasteland, Max is a testament to mankind’s formidable survival instinct in the face of certain doom.

In the dreary twilight of our end-time narrative, a contest for dominance assumes the primary role, casting a pall over the desolate landscape. Recalling Nietzsche’s profound assertion, “All life is a dispute over taste and tasting,” this intense struggle for control illuminates the tragicomic theater of existence within this cursed terrain. Here, power, like the fading heartbeat within the chest of a mortally wounded creature, stands for life itself – a symbol of the persistent will to endure, an epitaph to the stalwart Faustian spirit. On one hand, there exists the merciless horde of Lord Humungus, hunters in this barren wilderness, their thirst for “guzzoline” a grotesque parody of the civilized man’s greed, a melancholic reminder of our unchecked avarice. On the other, there are the beleaguered denizens of the refinery, akin to the last garrison of a besieged fortress, clinging desperately to their sanctuary, their last semblance of order in a world gone mad. Their ceaseless defense, a testament to mankind’s unwavering resolve, forms a spectacle of resistance against the predatory might of the marauders. Thus, this pursuit of power, this Danse Macabre of survival, is nothing less than a bizarre mirror to Nietzsche’s somber maxim, a reflection cast in the ashen dust of a dying world.

Within the bitter and merciless confines of The Road Warrior, God exists as but a phantom of forsaken hopes, a relic cast away in the cruel storm of survival. Morality, once a revered compass guiding man’s actions, now lies discarded, a forsaken artifact of a world long since devoured by anarchy. This nihilistic panorama stirs to life Nietzsche’s cold and disquieting inquiry, a question that murmurs like a winter wind in the heart of the desert: “Is man merely a mistake of God’s? Or God merely a mistake of man’s?” Within the barren wastes of the badlands, the chiseled law of nature – the survival of the fittest – becomes the new gospel. It sings a violent hymn, echoing the cacophonous clash of steel and the desperate cries of the dying. In this stark melody, the solemn contemplation of Nietzsche resonates, a lament to God’s demise and the termination of traditional morality. It paints a morbid picture of the world, in which the divine is dead and the ethical norms of yesteryears lie buried beneath the rubble of the apocalypse. The tale weaves a testament to the will to power, the triumphant proof of mankind’s capacity for survival in the face of existential dread, thus paralleling Nietzsche’s thoughts on the new order, born from the ashes of the old, divinely sanctioned morality.

At the very core of Nietzsche’s notions lies the concept of the Übermensch, a superior entity surmounting the limitations of ordinary mankind. Keeping in mind Nietzsche’s chilling dictum, “Man is something that shall be overcome,” this idea finds expression in the dark and melancholic figure of Max. An apparition in this forlorn realm, Max first appears as a specter of survival, a solitary silhouette navigating the unforgiving wilderness, his sharpened instincts rendering him as keen and deadly as the weapons of the marauders in his midst. Molded by this ruthless world into a stoic warrior, his once crystal-clear morality is obscured by the harsh reality of existence, his humanity shrouded in a veil of cynicism. Yet, as our tale spins its web of despair, Max undergoes a metamorphosis. His hardened exterior begins to crumble, revealing beneath the survivalist a beacon of redemption and hope. In the heart of this bitter warrior flickers a flame of the Indo-European spirit, warm against the frigid air of the wasteland, a living testament to Nietzsche’s Übermensch. Max, once the archetype of the survivalist, gradually becomes a guardian of the weak, his self-sacrifice a beacon piercing the darkness. His evolution from an ordinary man to Nietzsche’s superhuman concept showcases the possibility of transcendence, even in a world seemingly devoid of humanity. Thus, Max emerges not merely as a hero, but the personification of Nietzsche’s prediction – the ultimate symbol of mankind’s potential to overcome and ascend.

As our tale spirals inexorably towards its grand denouement, the ghostly whispers of Nietzsche’s prophetic utterance resonate in the poisoned atmosphere: “What is great in man is that he is a bridge and not an end.” Max stands on the precipice of this profound revelation, poised to embody Nietzsche’s envisioned greatness. In a heroic act of self-sacrifice, Max offers himself as a decoy, a lure to divert the marauding predators away from the besieged sanctuary of the refinery colonists. In this moment of supreme surrender, Max is transfigured; he metamorphoses from a hardened survivalist, a lonely wanderer in the barren wasteland, into a savior, an ephemeral beacon of hope in a world starved of it. He becomes the bridge to survival for the colonists, his actions paving the way for their deliverance, his sacrifice securing their escape to a hope-filled horizon. Thus, Max’s transformation encapsulates Nietzsche’s concept of mankind’s potential for greatness, reflecting the ability to transcend one’s own existence for the welfare of others. His journey becomes a testament to the bridge that man can be, not merely an end, but a conduit for survival, redemption, and hope in the direst of circumstances.

In the cold, harsh aftermath, our story draws to a close on a sobering note from Nietzsche: “The snake which cannot cast its skin has to die. As well the minds which are prevented from changing their opinions; they cease to be mind.” Once more, Max stands as a lone pilgrim, shedding the remains of the past, ready to embrace the new order. This evolution of Max epitomizes Nietzsche’s philosophy of intellectual growth.

The Road Warrior thus paints a grim panorama that extends beyond the boundaries of traditional cinema. It amplifies Nietzsche’s philosophical principles within the stark backdrop of a ruthless, chaotic world, where survival stands as the ultimate testament of the Faustian will. Nietzsche pens, “One must still have chaos in oneself to be able to give birth to a dancing star.” This ideal represents the emergence of beauty, order, and creativity out of turmoil and confusion. Max, amidst the chaos of the apocalyptic wasteland, manages to cultivate a sense of purpose and evolves beyond mere survival, effectively embodying this dancing star. His journey represents a dance of transformation, a symbol of light twirling in the desolate dark, much like a star dancing in the endless void of the night sky.

Following Nietzsche’s concept of “Eternal Recurrence,” a doctrine bearing the oppressive weight of endless repetition, The Road Warrior unfurls its narrative. As Nietzsche unsettlingly inquires, “What, if some day or night a demon were to steal after you into your loneliest loneliness and say to you: ‘This life as you now live it and have lived it, you will have to live once more and innumerable times more?’” This nightmarish hypothesis finds its corporeal manifestation in the bleak saga of Max. Like the indifferent sun traversing the yellow sky in a relentless cycle, Max’s existence is a pendulum of survivalist struggle and solitary exile. His life, a symphony of struggle against marauders, of the ceaseless quest for vestiges of humanity amidst the vast wasteland, mirrors Nietzsche’s vision of life’s ceaseless repetition. After his monumental sacrifice to ensure the escape of the besieged settlers, Max does not find solace in the tranquil haven of victory; rather, he is ensnared back into the vast expanse, the shadow of his solitary journey ever stalking his steps. This cycle of confrontation and isolation, of valor and vanishing, is a stark illustration of the eternal recurrence of Max’s existence – a merciless loop that exemplifies the endless return, embodying the dread of a life lived repeatedly, ad infinitum, a potent enactment of Nietzsche’s somber philosophy.

Yet, amidst the pall of death in The Road Warrior, a glimmer of hope persists, best captured in Nietzsche’s sage words: “In spite of pride, in spite of great intelligence, in spite of beauty, in spite of all spiritual distinction, man will have to give recognition to the sense of truthfulness.” The Gyro Captain, a nomadic scavenger beneath whose eccentricities pulses a compassionate, courageous heart, and the Feral Kid, wielding a deadly boomerang yet untouched by the surrounding brutality in his innocent curiosity, serve as beacons of sincerity amidst the ruins. They bear testament that even in the remnants of civilization, the essence of human dignity can endure, resonating with Nietzsche’s reverence for truth in man.

In conclusion, The Road Warrior manifests as a morbid portrait embodying Nietzsche’s philosophy. Unraveling the epicness of Nietzschean thought reveals the movie’s deep exploration of the Faustian condition – its incessant quest for power, its continuous struggle for survival, its grappling with morality, and its potential for transcendence. In the guise of Max, we glimpse Nietzsche’s envisioned Übermensch – birthed from chaos, evolving, recurring, and a testament to mankind’s unbreakable spirit.

Max’s whole life and philosophy is based on rivalry. The “False Dilemma Fallacy” he lives and exudes simply continues the push pull of society. Yes, he has to be this way to survive, but at what cost? Underneath the manifesting principle is not survival, it’s fear. As Gandhi said, “The enemy is fear. We think it is hate, but it is fear.” Though the film was made overseas, it reflects the standard mythos of the old cowboy films, the lone male hero riding over the hill to save the day. It’s just amped up. Instead of cowboys and Indians, it’s cowboys vs. cowboys.