I had to work very hard to kill the sentimentalism in me. I had to kill it, because sentimentalism is forbidden for a novelist-surgeon. This haze inevitably distorts the way we see things and makes us lose our sanity. Nevertheless, sentimentalism is a constant for men, and even when they think they have got it all sorted out, it lives on in strange ways in other places.

– Yukio Mishima, The First Sex

Over the past fifty or so years, and reaching a turgid and frankly insufferable crescendo over the last three, as a concept, safety – or rather, the perception of safety – has triumphed over reason. Feminine values, such as nurturing and inclusivity, have been given far greater weight than the masculine values of heroism and intrepidity. So great was this manic desire for safety that a threat was manufactured; after the non-threat that can best be described as a “pandemic of data,” the false threats of racism, sexism, and various other “-isms” continue to be bandied about as threats, and anyone who denies the validity of these threats is routinely demonized and subjected to all manner of censure and insults.

“The meaning of ‘-ism’ and ‘need’ can be bent in any way depending on one’s perspective. And even if we interpret it in a common sense way, it remains possible to explain what it means to have an ‘-ism’ in various ways,” Ryūnosuke Akutagawa wrote in a piece titled “On -isms.” The brief essay is just as prescient today as it was in Taishō-era Japan. “Originally, the -ism was a device proposed by critics for the sake of expediency, so it is not possible to conceal all the tendencies of one’s own thoughts and feelings with it. If they were not all hidden, there would be no need to use them as a title.” The -ism, Akutagawa then argues, is nothing more than a convenience, a trifle, a method for those of below-average intellect to employ in order to give the appearance of eloquence when there is none to be found. When discussing feminism, then, a term that can be challenging to define in a society where women enjoy both equal rights and special protections, we encounter a doctrine that asserts a woman’s will should not be limited by gods, nations, husbands, fathers, or even children. As such, women are more often than not allowed to say whatever slanderous and injurious things they like. “Believe all women,” they say.

Of course, I reject the very premise of the juvenile taunts of those who see the specters of sexism, racism, and the myriad “-isms” lurking in even the most innocuous remarks, but for many, and especially for men, their jobs and livelihoods are at stake. Men are expendable. After all, in America, which jobs were designated as “essential” during their totalitarian lockdowns? The traditionally feminine jobs of teaching and nursing. How ironic, then, that these “caring” professionals are often the most petty. Needless to say, it is often women who most vehemently advocate vindictive, punitive actions against the opposite sex whenever they perceive an insult. Truly, these actions resemble nothing if not a bizarre maternal scolding, but done in the most childish way possible: essentially, it is nothing more than name-calling. The phrase “land of the free and home of the brave” has become somewhat outdated in today’s context. What is it that led to this shift?

Considering how the concept of “science” has been at once deified, perverted, and weaponized by the radical American left, I often consciously and deliberately eschew it. There are writers far better suited than I to describe such a biological phenomenon, and many of them have already done so in describing the various and complex innate differences between men and women. However, I can at least offer my own observations. The most obvious, at least in my estimation, is the feminine overvaluing of emotion – and far beyond this, overt and deliberate public displays of emotion – and sentimentality, although in recent decades, this is increasingly applicable to men, as well. One can easily attribute this to an excessive amount of maternal influence. That is, children are raised by mothers whose husbands would dare not tell them “no” lest they be labeled misogynists, and in return these women never say “no” to their children, so long as their children conform to their designs. Even among mainstream so-called conservatives, this is a common dynamic. Many American fathers seem to fear their boys growing into men. This dynamic results in what can most charitably be described as coddled weaklings. Their daughters grow up to be spoiled tyrants, and their sons often become at least somewhat effeminate, and tend to eventually marry women who are at least as domineering and abrasive as their mothers and sisters. And thus the pattern repeats itself. This is not to say that men should be needlessly cruel or legalistic, as seen in certain anti-intellectual strains of Protestantism. As Yukio Mishima wrote in The First Sex, “The tyrannical husband torments his wife, makes his children cry, wastes money, drinks heavily, manipulates women, and appears to have no delicacy whatsoever. However, many such men are actually very weak-minded men who resist their own ‘compassion’ and end up like that.”

We have often heard the phrase “the future is female,” but it is unlikely to be exclusively so. While feminine influences may presently hold sway, they will increasingly come to rely on artificial structures for support, such as technology, feminist-influenced institutions like universities, or the administrative state, which refers to the rule-making process carried out by various American federal agencies outside the purview of Congress.

The decadence present in such a bureaucratic society is obvious. Yes, safety has triumphed over reason. These coddled and indulged moderns represent a truly bizarre combination of overweening self-esteem and fragile self-concept; in a sense, these people have very little sense of self. Their identities invariably revolve around the groups to which they belong – their race, sexuality, etc. Of course, even their identities revolve around “-isms,” and so their selves are fractured. They value themselves to the utmost, but they have no sense of individuality, and, moreover, they typically behave entirely without dignity. Indeed, they routinely show contempt for the very idea of dignity, a typically masculine concept. Strength and intelligence, too, are regarded with disdain by such people.

“Men are stronger than women only in terms of strength and intelligence, and men without strength or intelligence are not superior to women in any way. This intelligence, too, was originally developed by men to cover their own emotional weakness and not to be outdone by women,” Yukio Mishima wrote in The First Sex.

I believe that the prevailing female-dominated society in which we live aligns quite well with the twentieth-century concept of the superhero. Of course, such a society has no use for the Nietzschean superman, only the sanitized comic book character. Societies that undermine traditional masculinity can easily accept such absurd superheroes, as they primarily serve as figures of imagination for children, rather than embodying political ideals. These superheroes were initially meant for children because there is no possibility of attaining their powers, which are purely fictional, and yet these films remain inexplicably popular among adult men and women. Naturally, in these superhero films, there is never a real sense of danger, and the concept of sexuality is largely absent. The superhero will never die, never mind die “at the right time,” as Zarathustra said; if the superhero dies, invariably, he is reborn or resurrected. I find this to be laughable in a society that has abandoned religion. “God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him,” wrote Nietzsche. America has abandoned the hero for the superhero. The subculture surrounding superheroes is essentially juvenile.

“A man is often defeated by his own ‘compassion.’ They take countermeasures and are unable to turn back. Then the ‘female enemy’ is formed. The story goes like this…” Mishima continued.

America especially has a uniquely modern and particularly feminine aversion to death. The death of a grandparent or great-grandparent is often viewed as an unprecedented tragedy. In the past, such deaths were recognized as the natural course of things. Obviously, one is typically predeceased by one’s elders. Such events should not require grief counseling, and yet I have observed multiple adults, some of them well past middle age, view these deaths as great traumas. But if every death is a tragedy, then, can any death be regarded as a tragedy? Of course, death had always been feared, but it was nonetheless viewed as an unavoidable and inevitable aspect of life. In the modern era, death is not seen as an inevitable progression of life, but is instead seen as a dreadful and terrifying “other” to be avoided at any expense. As such, safety is paramount under the modern regime, even if it renders life unlivable. “There is nothing so painful as able limbs denied motion,” Sōseki Natsume wrote in The Tower of London, describing incarceration. “To live is to move. Deprived of activity, one is robbed of the meaning of life, and it is more painful than death to be conscious of such a state. The pain of what one’s lost renders the living lifeless.”

To discuss this is beyond taboo, of course, and in some especially “progressive” circles, this is tantamount to violence. Phrases such as as “public health” and “collective good” continue to be thrown about, as if these things are self-evident. It is the nature of totalitarian societies to conceal their atrocities under the banner of a larger, collective good. Naturally, within this collective good, there is no place for the individual. This, too, is especially feminine. The group is protected at the expense of the individual. Moreover, the mediocre are valued at the expense of the exceptional. Safety and collectivism are valued over heroism, genius, and individual distinction. In the East, this can be described as an overvaluing of the yin element – favoring the moon at the expense of the sun; favoring the dark and the damp at the expense of the light and the solid. In such a climate, darkness has proliferated. Politics has been made the pastime of the masses, rather than the domain of great men. Myth has been abandoned, replaced by superheroes.

One should not aspire to something that is clearly impossible and deliberately designed to be so. Nor do exceptional individuals entertain fantasies about possessing such superhuman abilities. This is the delusion of the mediocre. Rather, exceptional individuals tend to focus on soberly assessing their own potential, honing their skills, and learning from the greatest human exemplars of the past. These superheroes appear to convey a similar moral lesson; however, they are accepted as long as they serve society and are only deemed significant if they cater to the needs of the masses. This is twisted to reflect a typically communistic theme.

“What I want to say is that which ‘only men can understand,’ women cannot understand anyway, so please respect what you do not understand and leave it at that, instead of blindly and outrageously condemning it or interpreting it in your own way. It is to say that it should be respected as a matter of course,” Mishima wrote.

Therapists and social workers assert their understanding of what masculinity should be, which, unsurprisingly, aligns closely with qualities traditionally associated with women, though not necessarily in the conventional sense. Very literally, these days, women overshadow men. It is hardly uncommon to see women who outweigh their husbands – wives of 5’4″ who weigh more than their 6’2″ husbands. Meanwhile, their happily emasculated husbands embrace this. The men who marry these large and domineering women of course refuse to decline even the most unreasonable and frivolous of their wives’ whims. To do so would be regarded as oppression, as “patriarchy.” From my own observation, many of these men would honestly feel guilty if they were to find themselves attracted to a traditionally attractive and feminine woman. In the modern American gynocracy, beauty, much like strength, is regarded as a sin. Intelligence, as well, is regarded with suspicion. Literacy is written off as a masculine and “White” value. The culture of America is truly one of emasculation. The myth of toxic masculinity primarily aims to undermine male self-assurance and their perception of their societal roles. Such concepts have also contributed to the ongoing gender and pronoun debates in America. The concept of toxic masculinity, with its subtle manipulations, aims to denigrate masculinity itself, suggesting that it is an artificial, learned, and harmful construct devoid of any natural foundation. It purports to harm everyone, particularly women, but also men.

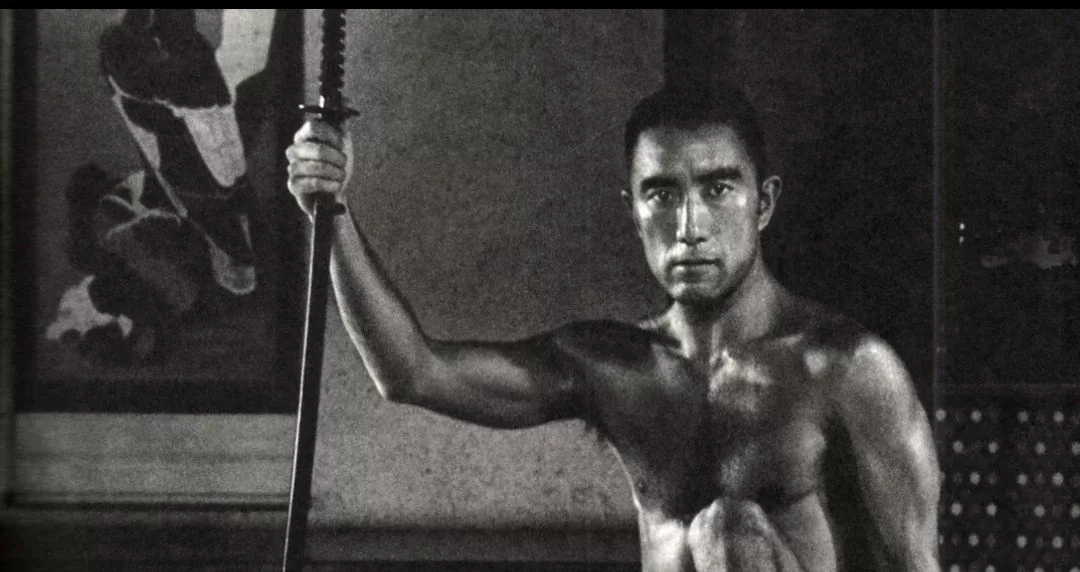

Masculinity, as a virtue, will no doubt experience a resurgence, but it will not manifest in the form of superheroes. Rather, it will bear closer resemblance to the qualities embodied by figures such as Toshiro Mifune and Charlton Heston. The concept of masculinity is often discussed in terms of physical attributes and appearances. Women frequently describe their ideal man as tall, athletic, and masculine. However, masculinity extends beyond mere external features.

It is irrational to assume that a man’s height alone determines his level of masculinity. Absurd arguments that suggest a man measuring 5’11,” 6’1″, or 6’4″ is inherently more manly than a man of 5’5″ hold no weight. As Yukio Mishima wrote, observing gangsters, one often finds that the bosses are typically diminutive individuals with lackluster appearances, while the towering figures of six feet are regarded as mere subordinates, petty thugs.

I make these observations without prejudice. If we disregard the invisible aspects of masculinity and focus solely on external appearances, this becomes easier to comprehend. Certain faces and bodies exude masculinity. Toshiro Mifune and Charlton Heston are Mishima’s examples of such individuals. Sadly, and no doubt due to the preferences of modern women for unmasculine men, it is difficult to come up with such examples these days.

I cannot speak to the personal lives of Mifune and Heston, but as Mishima points out, there are many instances where men possessing masculine looks and physiques find themselves in the kitchen making omelettes, monitoring the prices of rice in household account books, playfully teasing their wives over trivial matters, or happily tending to household chores. Appearances can indeed be deceiving. Once we consider masculinity in abstract terms, divorced from external appearances, we are astonished by its elusive and intangible nature. According to Mishima’s ideal, a completed man should be both a warrior and a poet, his nature comprised of both bravery and sensitivity. “But you can’t have a brave conversation with a woman,” he wrote. “The English word ‘delicacy’ is best translated as ‘thoughtfulness.’”

Masculinity does not solely revolve around disregarding minor details, as modern sitcoms so often depict. Even if a man claims to be unconcerned with trivial matters, carelessly stepping on a napping cat at his feet would be a distraction. True masculinity lies in being attentive and perceptive to every detail while distinguishing between the significant and the insignificant, avoiding fixation on trivialities. Masculinity can be regarded as synonymous with “objectivity” or “objective judgment.” Self-proclaimed intellectuals like Ta-Nehisi Coates or Anthony Fauci, who resemble sports commentators making omniscient “objective judgments,” cannot be considered truly masculine.

Constantly making decisions without taking action does not exemplify masculinity. The moment a man decides to take action, he becomes extremely subjective, embracing romanticism and sentimentality. A man who acts incessantly without much thought often possesses a sentimental nature, even more so than a schoolgirl lost in reverie. Sentimentalism, therefore, does not encompass the essence of masculinity.

The notion of “masculinity” generally originated in feudal societies of the past. In Japan, a boy would be born and dedicate his life to his lord and country. To fulfill this role, he would immerse himself in martial arts, lead his men, and be prepared to sacrifice his life at any moment; at times, he would be expected to follow his lord in junshi, or ritual death. Such a man is perhaps best embodied in the figure of General Maresuke Nogi, who waited for thirty-five years to follow the Emperor Meiji in death, committing seppuku just as the cannons were fired to announce the Emperor’s funerary parade. This simple definition of masculinity left little room for confusion, as adherence to this ideal would garner recognition from both society and oneself. In purpose-driven societies, men were employed for warfare while women were valued for procreation. Both masculinity and femininity were distinct and clearly defined. However, even in modern societies lacking clear objectives, remnants of the old masculine image persist in people’s minds.

Why is this so? It is because women have begun perceiving “masculinity” as a sexual object, leading to confusion. Due to the influence of American culture, ideals of manhood and the perception of women as sexual objects have gradually converged. As a result, the term “masculinity” has transformed to denote something akin to “rugged sexual attractiveness.” However, in Japan, “masculinity” retains a somewhat unsexual, sublime quality. In countries with long histories, such as Japan and France, the notion of the beautiful male still exudes a delicate aura, as seen in the figure of François Villon composing poetry as he was led to the gallows. The idea that a delicate man can be alluring persists in women’s minds. Therefore, men should devote themselves wholeheartedly to refining their masculinity. As Mishima wrote, the fiercely delicate, sword-wielding, moon-gazing “manly” man should commute on crowded trains to his modestly paid job each morning, often unnoticed by women.

In samurai-dominated societies, a man did not require the validation of women to be regarded as “manly.” Simply dedicating oneself to masculinity was sufficient. Masculinity was defined by something far more sublime than mere sex appeal. This should not be mistaken for the very modern sōshoku-kei danshi, or “herbivore man,” that is, passive and directionless men with little interest in romance, career, or art.

Regarding this, Mishima described a letter written by a woman in response to a newspaper column:

My husband watches a lot of war stories on TV and buys books about war, and I’m worried that he might have an adverse effect on our young boy, who is growing up to be warlike. I want him to grow up to be a peace-loving person, so I have been trying to keep his eyes away from such things, but my husband keeps messing things up. I have asked him many times to stop, but he just replies with a noncommittal gesture. What should I do?

Mishima saw a typical woman’s impatience upon reading this. If a boy was raised with such principles, he would die before he had a chance to develop into a man. “If a boy becomes belligerent, buy him a bamboo sword and let him practice kendo, and he will be dissipated. A peace-loving man is a castrated man.” No doubt, Mishima anticipated the sōshoku-kei danshi, and its American equivalent, the locavore.

I will end with a poignant anecdote from The First Sex:

A husband was sitting in silence on a Sunday afternoon, looking out of the window of his apartment at the sky.

‘Hey, what are you thinking about?’ his beautiful young wife would ask.

Some husbands may not be thinking about anything. Some days he might be absorbed in an outrageous fantasy about the panties hanging out to dry in the opposite wing. Other days he may be worried about the bar bill at the end of the month.

However, it is also possible that he is chasing a “dream that only men can understand,” profound and poignant thoughts that women cannot understand. At that moment, he is not just an ordinary 100-yen man, but a man among men, a great man.

But the man, without explaining much of anything, just kind of goes on and on.

‘Umm, just a moment ……’

And,

‘No, a ……’

He vaguely lies about it, and when he reaches the point of urgency, she says, ‘Idiot. I remembered your lovely demeanor when we were engaged.’

The woman continues to say the most absurd things, such as, ‘Oh, really? You’re an idiot.’

The young wife is satisfied. But then she doesn’t realize she’s let a very important man slip away.

I wish I had never attended College at all. That was, of course, the biggest mistake in my entire life. If only I had joined the military instead. My life would have been a whole lot different. Perhaps, afterwards, I could have gone into Law Enforcement. That would really have given my life some sort of purpose.

Well, anyway, I have always admired the Japanese, and their Code of Bushido. Perhaps, the Warrior Way lives in me to this day.

You make some really interesting points in your article. Nowadays, women can accuse men of stalking and/or sexual harassment for any reason at all, or even for no reason at all!