In my conversations with my good friend and mentor Tomislav Sunic, I was discussing with him the American thinkers who have had some influence on European New Right thought. Our discussion led me right back to his book Homo Americanus: Child of the Postmodern Age. Sunic gives us a treasure trove of American thought that is in the same vein of political thought as the European New Right and it comes from our friends south of the Mason-Dixon Line in Dixie. In this essay, I will be exploring the thought and works of the 12 Southerners.

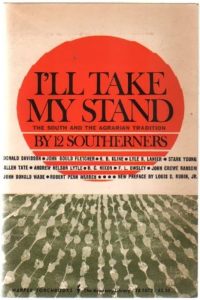

I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition is a thought-provoking manifesto written by twelve Southern intellectuals known as the Southern Agrarians or the Twelve Southerners. Published in 1930, this collection of essays offers a robust defense of agrarianism, critiques of industrialization, and an exploration of Southern identity. The authors advocate for the preservation of agrarian values, localism, and traditionalism while expressing concerns about the detrimental effects of modernity on society. In their criticisms we can see the foundations of an American school of anti-globalist thought.

“Northern Industrialization,” a phrase any American is familiar with from his grade school education of the American Civil War, can be better understood as the seeds of American globalism. Written decades after the Civil War, the Twelve Southerners expressed deep concern over the rapid industrialization sweeping through the South during the early 20th century. They criticized the relentless pursuit of progress and profit, which they believed devalued human relationships and traditional customs.

The authors warned against the alienation and dehumanization that came with industrial labor, contrasting it with the perceived sense of community and belonging in agrarian societies. They criticized the alienation of labor that accompanied industrialization. They argued that the division of labor in factories stripped workers of a holistic understanding of the production process, reducing them to mere cogs in a vast and impersonal machinery. This separation from the final product and the monotony of repetitive tasks led to a sense of disconnection and detachment among industrial workers.

Industrialization fueled a culture of materialism and consumerism that the Southern Agrarians found deeply troubling. They believed that the relentless pursuit of material wealth and possessions overshadowed more profound values and spiritual fulfillment. This preoccupation with material gain was seen as detrimental to individual character and societal well-being. The rapid changes brought about by industrialization were viewed as eroding traditional values and social structures. The Southern Agrarians feared that the pursuit of material success and individual gain would weaken the bonds of family, community, and faith that they held dear. They saw industrial society as promoting a utilitarian outlook that undervalued the importance of tradition, heritage, and collective memory.

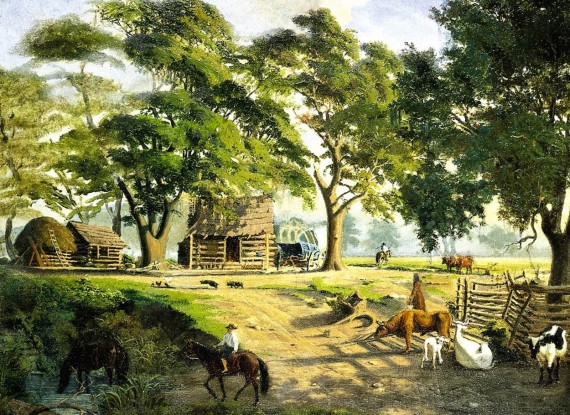

The Southern Agrarians felt that industrialization was a threat to their culture, identity, and way of life. For the Southern Agrarians, preserving tradition and heritage was vital to maintaining a distinct sense of identity. They looked to the past as a source of wisdom and guidance for the future. By cherishing and passing down customs, stories, and cultural practices, they believed that Southerners could maintain their unique identity in the face of modernization and industrialization. Rootedness in tradition was seen as a means of resisting the homogenizing forces of modern society. The concept of rootedness revolves around the deep connection individuals have with their land and environment.

The Southern Agrarians celebrated the agrarian way of life, where families often lived on the same land for generations, developing a profound sense of place. They believed that the land shaped people’s values, customs, and character, and being rooted in a particular place provided stability and continuity in an ever-changing world. This rootedness in the land cultivated a profound attachment to the South’s rural landscape and the agrarian lifestyle. The Southern Agrarians believed that rootedness was closely tied to cultural identity and values. Embracing their Southern heritage and agrarian roots allowed them to affirm their values, such as a preference for localism, individualism tempered by communal responsibilities, and a reverence for tradition. Rootedness was viewed as the foundation of Southern identity, shaping the way Southerners viewed themselves and interacted with the world. By cherishing their agrarian past, the Southern Agrarians sought to preserve their distinct Southern identity and resist the homogenizing forces of the industrialized North.

According to one of the authors, John Crowe Ransom, Southern identity is unlike that of the North, which prides itself in its rejection of Europe in the name of Progress. Instead, to quote Ransom, “The South is unique on this continent for having founded and defended a culture which was according to the European principles of culture; and the European principles had better look to the South if they are to be perpetuated in this country.” And to quote Allen Tate, “The South could be ignorant of Europe because it was Europe; that is to say, the South had taken root in a native soil. And the South could remain simple-minded because it had no use for the intellectual agility required to define its position. Its position was self-sufficient and self-evident; it was European where the New England position was self-conscious and colonial.” We find in the South a satellite of Europe with a truly European way of being in the world — they have no need to look to Europe because they are Europe.

Much in the same vein as Oswald Spengler, the Southern Agrarians viewed industrialization and its manifestations as evidence of decay of Western life. To quote Lyle Lanier, “Modern industrialism has found the use of ‘progress,’ as a super-slogan, very efficacious as a public anesthetic… General sanction of industrial exploitation of the individual is grounded in the firm belief on the part of the generality of people that the endless production of material goods means ‘prosperity,’ ‘a high standard of living,’ ‘progress,’ or any one among several catchwords… This belief is strengthened by certain popular ‘interpretations’ of the spirit of America which proclaim a mystic faith in the industrial destiny.”

We find in the Southern Agrarians a harsh criticism of the American religion/philosophy of “Progress.” To them, Progress is nothing more than a myth, fueled by industrialization, that is poorly defined and working towards a highly desired, yet undesignated endpoint. Today, we find the march of Progress as justification for the LBGT agenda and endless mass immigration. What is the end goal of all this? Is there one? The Southern Agrarians saw through this facade with the lens of realpolitik. To quote Frank Lawrence Owsley, “Unfortunately for the South, the leaders of the North were able to borrow the language of the abolitionists and clothed the struggle in a moral garb. It was good politics, it was noble and convenient, to speak of it as a struggle for freedom when it was essentially a struggle for the balance of power.” Similarly, we see today, whether it is the advancement of domestic or international policy, the rhetoric is always about the struggle for “freedom,” “democracy,” or “human rights” – it is really about the expansion of political power.

Americans looking for domestic inspiration for their own New Right intellectual movement will find what they are looking for in the Southern Agrarians. Their manifesto, I’ll Take My Stand, is an invaluable document which can serve as the foundation for a school of anti-globalist, identitarian thought.