If nihilism, according to Nietzsche, is to deny the importance of the highest values – the aristocratic values – it is also to deny the value of ‘what exists’. And what exists is the earth, nature. Hence, some portray Nietzsche as a thinker of ecology, or even a pioneer of it. However, as always, the reality is more nuanced than that. At the same time, it is infinitely clearer than any oversimplification of Nietzsche to simplistic slogans.

Nietzsche is a perspectivist. One must – and it is apt to say – not lose sight of this. He is not interested in nature in and of itself. He does not possess the naivety to think that we can understand nature independently of the fact that nature is, precisely, thought of by thinking humans. ‘How beautiful the mountain is’, sings Jean Ferrat. Of course. It is beautiful from the perspective of man. From nature’s viewpoint, the mountain simply exists. And that is all there is to it. ‘It exists’, Hegel said.

What interests Nietzsche about nature is primarily its diversity. It allows humans to engage and immerse themselves in different climates, meaning in various landscapes, living conditions, heat and cold, moisture and dryness, and so on. What intrigues Nietzsche is that nature equates to life. It is not static; it continuously renews itself. In this regard, it mirrors the human as Nietzsche sees him. And in fact, it is man who reflects nature, if we momentarily shift our perspective.

Finally, what Nietzsche can help us understand is that nihilism can also reside in our tainted relationship with nature. This relationship can be distorted in several ways. One of these can be the instrumentalisation of the world. Nature is there to be exploited without respect or limits. This is what Günther Anders and Martin Heidegger criticise. Nihilism can also be found in a doomsday view of ecological problems. ‘Humanity will disappear. Good riddance!’ proclaimed Yves Paccalet in 2007 (though one should not be fooled by the author’s provocative stance in the face of the very real devastation of the earth). This leads to positions considering man the root of all problems, and hence, we should stop reproducing, especially in Europe. The goal: at the least, leave more space and resources for the less ‘developed’ peoples; at most, vanish altogether.

A Reversed Prometheanism

From this anti-human ecological standpoint, Nietzsche’s ‘last man’ is not just the lowest form of man; he is quite simply the last one remaining before the complete disappearance of humanity. ‘Please close the door behind you.’ In reality, whether one views the earth solely as a resource to exploit, or, on the contrary, as ‘nature’ that needs protecting by ridding it of man, one misses the essence of man’s place in nature. The earth can withstand the worst human ravages. It will still persist unless the cosmos burns, cools, or disintegrates it. What humanity alters through neglecting ecology is not the planet itself, but our relationship to it. It is the earth for its own sake. A polluted, depleted, overmined, overpopulated earth is simply an ugly earth. It is not inherently ugly – as the earth does not reflect upon itself. It is ugly to us. Its ugliness is based on human perception. It makes us unlearn beauty. It deprives us of the feeling that the world is inhabited by gods, not just by humans.

Thus, there are two forms of nihilism to avoid, and that is what Nietzsche helps us understand. One is the nihilism of sheer predation until the earth is exhausted. The other is the nihilism of humanity’s suicide to purportedly ‘save the planet’. A reversed Prometheanism, but Prometheanism nonetheless. Even in wishing to end himself, man sees himself as a God (especially in this context). Cancel culture: a culture of erasure. At its end, and at the culmination of ‘wokism’, which is its younger sibling, is the cancellation of man himself. To avoid these two nihilisms, Nietzsche points us to another path. It is the inclusion of man within nature. We must respect nature because we must respect ourselves. Respect does not mean abstention. Nature is feminine. Respect means not being careless with it. Man is a part of nature, which should forbid him a relationship based solely on confrontation or instrumentalisation. Our view of nature is not natural; it is human. This is what Nietzsche helps us grasp. This could be the Übermensch, who is not Superman but is a man fully aware of being nature’s product, life’s bloom.

Of Gods and Men

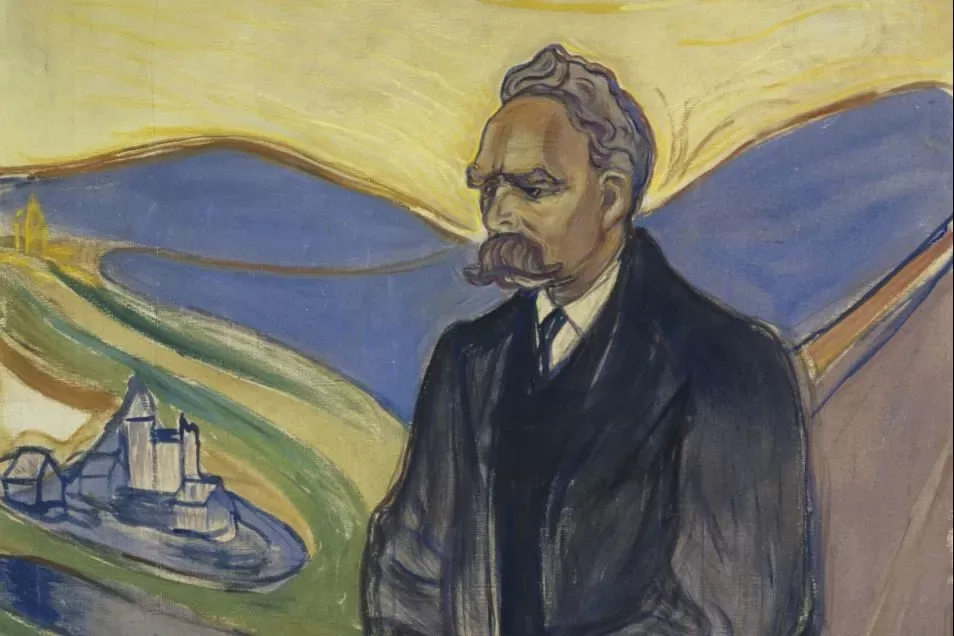

What does nature teach us? That life always finds its way. That it resists what denies it. This is negentropy (increasing organisation. Hegel said, ‘ever more institutions’, which meant the same thing). For Nietzsche, man is not at the centre of nature. We are not in Genesis 2:15: ‘The LORD God took the man, and put him into the garden of Eden to dress it and to keep it.’ 2:16: ‘And the LORD God commanded the man, saying, Of every tree of the garden thou mayest freely eat…”’ We are not within Christianity as a doctrine (even though we are partly within its civilisation, whether we like it or not). We move away from anthropocentrism or theocentrism, which amount to the same thing (theocentrism always being monotheistic). With Nietzsche, man is a part of the garden. He cannot claim his place based on a distinction between the earthly city and the city of God, in the style of Augustine of Hippo: ‘Two loves built two cities: the love of self to the point of contempt for God, the earthly city, and the love of God to the point of contempt for self, the city of God.’ Nietzsche decidedly steps away from this dualistic (and emasculating) schematic. Far from this distinction, man must instil sanctity upon the earth and in the world, a sanctity quite distinct from the misguided religiosity of monotheisms (whether they are egalitarian and universalist or supremacist). This is what Nietzsche wanted to convey. And this is what he demonstrated with his last living gesture: kissing a suffering horse. His final act: a gesture of love for life.

Neither the earth nor man should be reduced to nothingness. The idolisation of the earth must be rejected, just as the self-idolisation of a complacent and satisfied man should be. (The ‘self-god man’, Péguy mentions in Zangwill, 1904). This brings to mind the ‘last man’ from Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Just as we must reject the idolisation of a cruel and tyrannical God, we must replenish our imaginations with gods who guard the secrets of nature, ranging from the depths of Mother Earth to the farthest reaches of the heavens.