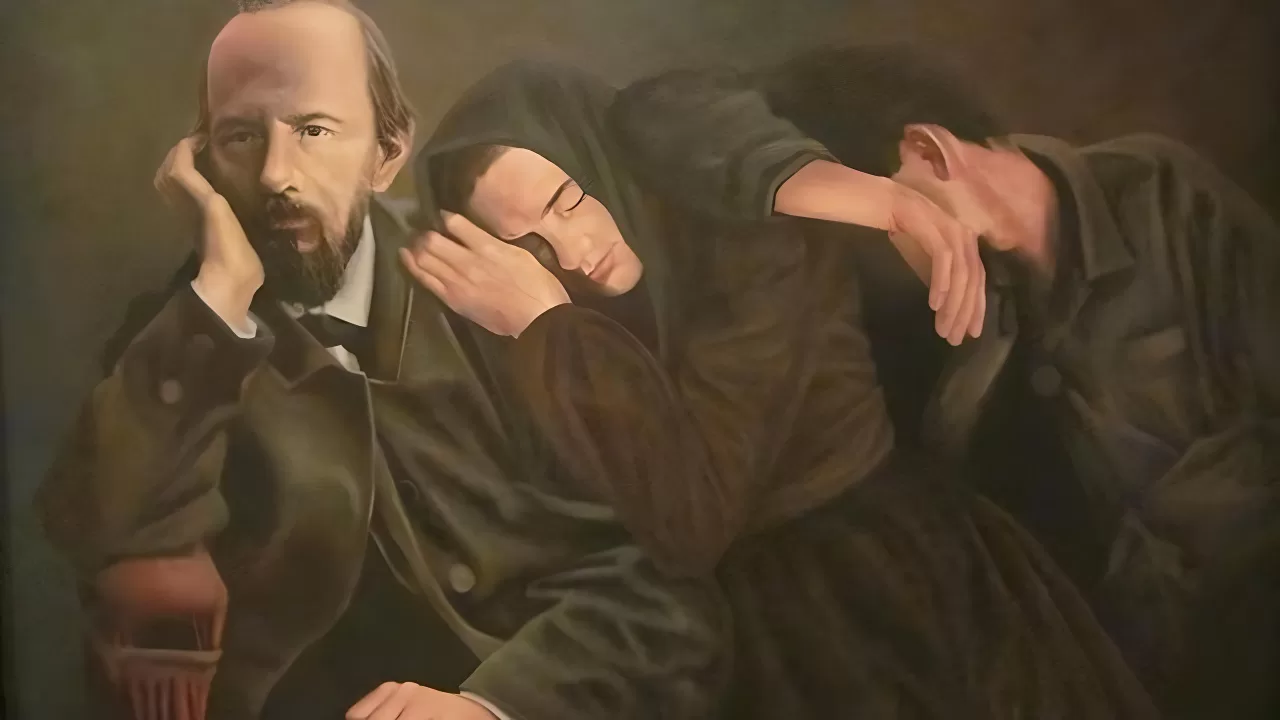

The I-novel first came into vogue near the end of the Meiji era and continued through the Taishō era and well into Shōwa. The term “I-novel,” called either shishōsetsu, or watakushi shōsetsu, refers to novels written almost verbatim from the author’s own direct experience. “… it is a novel that mainly tries to express the view of life from the viewpoint of the subject,” Taishō novelist and playwright Masao Kume wrote. “…However, it is not the same as an autobiography or a confession. It must be a novel. It must be an art form. This fine line, together with the problem of the state of mind I will explain later, forms the boundary between the so-called art and non-art.” He described these as “novels of the state of mind.” Naturalistic literature in Japan was first developed in the form of I-novels. Now, some of the finest works of fiction ever written can be categorized as I-novels. Grass on the Wayside by Sōseki Natsume, No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, Confessions of a Mask by Yukio Mishima, and Labyrinth by Takeo Arishima can all be considered I-novels. There are numerous Western works that can be counted as I-novels, as well. The Devil in the Flesh by Raymond Radiguet, The Sorrows of Young Werther by Goethe, The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath, and even The Great Santini by Pat Conroy can be called I-novels. When written well, these can be truly beautiful, employing the form of autobiography as a vehicle for introspection, reflection, and even, at times, subtle commentary on society. “The best parts of the works of the great writers that strike us the most are almost always those parts that have a strong autobiographical element to them. Dostoevsky’s depictions of his life before and after his false execution, his epileptic episodes…,” Masao Kume wrote. The finest I-novels explore the nuances of relationships between the individual and society, especially focusing on the complex interplay between competing desires, motivations, and intentions. Kume, a literary disciple of Sōseki and strong proponent of the I-novel, was correct in his prediction that the I-novel would soon become a mainstay of the literary world. He described the universal appeal of the realism of this particular literary endeavor, believing it to be a superior art form.

“First of all, I cannot believe that the art is, in the true sense of the word, the ‘creation’ of another life. I cannot have the exaggerated sense of supremacy of a literary youth of a previous age. And I can only think of the arts as a mere ‘recreation’ of a life that one has lived.”

The worst I-novels, however, can perhaps most adequately be described as masturbatory and self-serving vehicles for the author’s overweening pride and self-esteem. Often crudely written and riddled with colloquialisms, these are studies in unearned and unwarranted vanity, and often juvenile in terms of expression. “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside of you,” the American writer Maya Angelou so inelegantly wrote in I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. This, I consider to be a typical example of a poor and self-indulgent I-novel. Such works typify the modern incarnation of the genre. Indeed, this is the sort of writing that is relentlessly indulged by the modern progressive class and taught in public schools at the expense of the classics. American schoolchildren are more likely to have read Angelou than, say, Tennyson. Of course, I consider Angelou to be one of the pioneers of this new generation of Western I-novelists; in her work it is made quite clear that she finds herself very profound, making her the prime example of this literary phenomenon. Works such as hers serve as a template, as it were, glorifying the basest and most coarse and unrefined of human impulses, an exercise in the excesses of unfettered naturalism. They sing the praises of undisciplined emotion, divorced from any semblance of reason, tradition, or nobility. These pieces serve as testaments to unbridled ego rather than any sort of individualism. Indeed, as Ryūnosuke Akutagawa wrote, they are only remarkable in how like all the rest they are. They sing of the gratification of all immediate impulses, then claim victimhood upon the realization of the eminently predictable consequences. It is not them but society who is at fault. In writing these polemics, then, these authors ironically deny themselves agency. Their reasoning is often adolescent, perhaps because they are never encouraged to mature further.

The playwright Kan Kikuchi wrote that one should not write a novel until he has lived a life of twenty-five years. Masao Kume, commenting on this, wrote, “He was probably trying to say that if you do not attain this state of mind, you should not write a novel, or at least not publish one. If I may use myself as an example, it was only in recent years that I have come to realize this state of mind. Ironically, my creative power has been greatly reduced since then, but I have a feeling that the only time I will be able to write anything that truly resembles a novel is after that time. And while there may have been some good things written before that time, some of them may have been ill-informed, but I have the feeling that they were mostly the negligent mistakes of a young man in a youthful frenzy. Of course, youthful faux pas are fine, but they should not be the end of the story. At the same time, we must not confuse the self-acquired state of mind with the author’s stagnation.”

These stagnant, modern incarnations of the I-novel are typically centered around the narrator-protagonist’s struggle to overcome some sort of adversity. These are nothing if not formulaic; it is as though there is something resembling the Hays Code of 1950s Hollywood in the field of literature. Mainstream publishers attempt to suppress anything that does not meet these standards. Their “struggles” are often blown many, many times out of proportion, and moreover, they are simply uninteresting. Regarding plot, many of these works can simply be summarized as “woman/minority feels oppressed.” How many times is it necessary for the same story be told? The protagonist, depicted as indomitable yet oppressed, invariably clever, rather than intelligent, overcomes whichever “-ism” is presently en vogue. These I-novels rarely have anything to offer beyond leftist political doctrine. They offer little psychological insight, although coming away from reading one of these, one may deeply and profoundly realize the vapid narcissism that pervades modern society. Such authors seem to be the product of excessive maternal coddling.

Taishō and early Shōwa I-novels, at least the best of them, are stylistically beautiful, rich in introspection, and often dissect the author’s own self-loathing. The modern I-novelists have little of either, although they are rife with self-pity, and yet they will vehemently claim that society demands that they be ashamed of their “blackness” or “queerness” or what have you. But once again, walk into any bookstore and it is frightfully plain that such stories are promoted at the expense of other voices, trampling those deemed irrelevant, unimportant, or “problematic” by corporate America. Female novelists seem to be given priority, and strangely, it seems that a greater proportion of male novelists seem to write under initials. This is of course anecdotal, but one can easily come to the assumption that this is done to conceal their gender. Perhaps a book by J. Doe will be more popular than one by John Doe, for women seem to prefer books written by their own gender.

The best I-novels are pure poetry, in which the author coldly and relentlessly dissects his own soul, including his failings. There is a fine distinction between confession and grovelling, between artistic reverie and pompous self-indulgence, between existential agony and self-pity. The finest I-novels push this tenuous balance to operatic perfection. They are melancholy, but never maudlin. “An artist must above all else strive for the perfection of his work. Otherwise, his service to the arts would be meaningless. Humanitarian inspiration, for example, can also be obtained by simply listening to a sermon if that is all we seek. As long as we serve the arts, what our work gives us must first and foremost be artistic inspiration. There is no other way to achieve this than to strive for the perfection of our work,” Ryūnosuke Akutagawa wrote in his column “Art, etc.” This is nothing if not directly contrary to the modern view of art as a vehicle for so-called social justice – that is, art as propaganda.

“After all, the foundation of all art lies in the ‘I.’ In that case, the expression of the “I” in a straightforward manner without any other guile, that is, in the art of prose, the ‘I-novel’ must clearly be the main way, the foundation, and the essence of the art. To put something else in place of it is only a means or method to make the art form commonplace,” Masao Kume wrote.

Frankly, most people lack the intellectual fortitude or artistic finesse to compose such novels. Most people do not know “I.” In many of them, it is as though there is no “I” to know; “we” would be more appropriate – “we women,” “we illegal immigrants,” etc. Moreover, most lives are simply uninteresting. There is no need for most stories to be told, for that is how art degenerates into tedium. Especially in this modern era, few shall ever experience anything resembling either triumph or anguish. Rare is the grand, sweeping tragedy. Modern I-novels typically reveal little more than petty indignities.

“Even the most inebriated life, even death and dreams, can have value if it is truly expressed,” wrote Kume, although I am not entirely in agreement on the matter. “As long as any human being who has ever existed on earth can be truly recreated, he can be of use to the future of humanity. It is inevitable that those who regard the arts as nothing more than a mere means of leisurely amusement and do not see them as a loving footprint of a person’s existence on this earth, but when we see them as part of the history of human life, each of us has the right to demand a page from each one of them.” This treatise on the I-novel was written in 1925, when writers such as Ryūnosuke Akutagawa and Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, who would one day be nominated for a Nobel Prize, dominated the literary scene. One is forced to wonder whether Kume would have changed his mind upon reading the modern records of grievances that pass for novels.

In the modern era, especially among certain classes, every indignity is perceived as a tragedy, and in these noxious modern incarnations of the I-novel, they are presented as such. A woman who is catcalled, for example, will present this as being tantamount to rape. Perhaps in her eyes this is true, and she believes this implicitly, but she believes this is true precisely because she is not an individual; she simply believes what so-called elite society has told her. Feminist media has told her that a flirtatious remark by a man deemed by her to be undesirable is the moral and ethical equivalent to rape, and so she believes this fiction without question. This is the era in which words are considered violent, after all. Truly, then, these automatons have uninteresting lives and are incapable of anything resembling insight. With their pens, a minor respiratory virus is transformed into Edgar Allan Poe’s Red Death, and race rioters and looters become freedom fighters. Criminals who are predictably killed as a result of their malicious antics become heroes and martyrs. The lives of these modern I-novelists are so bland that they seem to have no recourse but to make fictions of their lives. Naturally, then, they resort to florid melodrama. Perhaps this can be attributed to the media they consume, “consume” being the operative word. This is especially apparent in modern women’s literature. Let us return to the example of Maya Angelou, whose literary progeny can be seen in the likes of “poet” Amanda Gorman and Canadian I-novelist Alice Munro. Ordinary events are romanticized, and tedious detail becomes a replacement for substance. This hackneyed literature is elevated, and as such, their readers search for such grand meaning within their own unremarkable lives.

“But only those who truly recognize the ‘I’ within themselves and are able to express it exactly again in the written word will be tentatively called artists and will leave behind a legacy of I-novels. The word ‘exactly’ does not mean realistically, in the sense of ‘as it is.’ It is not to say that it is exactly as it is made from the material, although there is no distortion and there are no excesses,” Masao Kume wrote.

The Sōseki protagonist has been described by the critic Hideo Kobayashi as the prototypical Japanese Hamlet, a vacillating and passive figure torn between duty and individualism. In modern Western I-novels, neither is present. Duty is seen as oppression, and individualism is replaced with vainglorious egotism. These are self-serving tributes to deficiencies in character masquerading as refinement. Ironically, these are the same ideologues who engage in the copious use of such phrases as “white fragility,” which is always nebulously defined. This is nothing if not paradoxical. These people, usually women, are often hysterical, but there is no delicacy present in their frailty. Indeed, their constitutions, like their physiques, are invariably excessively robust. “White fragility” typically refers to occasions in which those of any vaguely European ancestry respond negatively to their neo-Maoist struggle sessions. In their eyes, a lack of sufficient deference, or perhaps even a lack of reverence, is a sign of fragility. This logic is, frankly, schizophrenic. It is the logic of those possessed of an excess of education in proportion to their intellectual capacity.

By any standard, these people are not deferential, and certainly not passive. They could not be further than Kobayashi’s description of the “Japanese Hamlet,” and yet they insist on portraying themselves as passive victims of the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune. They would like to have it both ways, if I must resort to a cheap colloquialism.

Maya Angelou wrote a total of seven autobiographies, and the details contained within are often inconsistent. I will not bore the reader with the particulars. However, the fact that such a figure remains so highly regarded in the panoply of modern literature is telling. European and male authors have been “cancelled” for far less. “Lived experience” is often used to invalidate reality. On one hand, these “artists” are naturalists, depicting the coarseness and ugliness of their lives without hesitation, and on the other hand they are fabulists, constructing their autobiographies – their I-novels – in order to sell their ideology. Truth has lost its meaning.

Perhaps it is better to simply call them what they are: hypocrites.