In a way, Argentina is the Ukraine of the south, considering its vast agricultural capacity and its high human capital, with a literate urban population since 1900, although the rural and proletarian masses had to wait a little longer and were only integrated into the national project in the decade of General Perón. Historically, Argentina went from being a periphery poorly administered by Spain, which allowed the country of the pampas to develop a happy economic autarchy, characterized by the picturesque gaucho with silver spurs and three meals of beef a day, to an informal British colony after the Independence of 1810 executed by the mercantile elites of Buenos Aires. Geopolitically, Argentina, and with it the Southern Cone, represents a platform of projection towards the Antarctic continent and adjacent waters, a horizon so far untouched by the exploitation of global capital.

Argentina’s political culture is marked by the populist and developmentalist experiment of Perón, whose first tenure gave an enormous impetus to domestic industrialization. However, the dirigiste program of import substitution and, contradictorily, the need to buy technology abroad, imposed on the Casa Rosada, the seat of government, a chronic need for loans, first in pounds sterling and then in dollars, to finance its own infrastructure. This dilemma is traditionally referred to as the “external restriction” in the economic literature and represents the mainspring of much of the zigzagging trajectory of boom and bust in the austral country. An early example of a payments crisis, whose depressive repercussions affected the entire world system, was the Panic of 1890. The conjuncture involved the Baring Bank of London and the free-market government of Buenos Aires. By then, such was its seriousness that the Bank of England itself intervened to rescue the insolvent Baring Brothers with fresh funds. Around the same time, Argentina accounted for half of all British investments abroad, rivaling, and often surpassing, formal colonies such as Australia, Canada or India.

Another aspect of Argentina’s political culture is the influence of different waves of immigration. Thus, against the liberal and cosmopolitan background of the Hispanic elites of the 19th century, there was the internal displacement of the mestizo masses and, simultaneously, the demographic avalanche of Italian workers, as well as the arrival of a dynamic Jewish diaspora of a quarter of a million people, a dislocation nourished by the Russian pogroms and the penury of the Second World War. Eventually, the local reception of Italian fascism and the different Marxisms would find their best explanation here. In practice, Peronism was fluid enough to accommodate both tendencies, while negotiating its political rise within the framework of conventional parliamentarism. The Argentine populist experiment, however, contained strong internal tensions, which tragically surfaced in the very civil war within Peronism, as reflected in the Ezeiza Massacre between the right and left wings of the movement itself (1973).

After the return of the neoliberal dictatorship of the putschist junta (1976-1983), Argentina abandoned the developmentalist industrialization project without relinquishing the rudiments of the welfare state. The distributionist agenda was thus fed more by foreign loans than by taxes on the real economy, whose factories and workshops had been strategically scrapped under imperial pressure. The mass democracy of the golden years remained finely hollowed out, although the political party oligarchies, driven by their typical kleptocratic inertia, continued with bribery, kickbacks and rentier bureaucratization. No austerity measure could stop the deficit snowball, to the point that ultra-liberal Macri (2015-2019) re-indebted Argentina with IMF loans equal to or worse than his predecessors. All in all, an interesting innovation of the post-dictatorial epoch, especially after the 2000s, was the change of the imperial leadership from London to Washington, and with it the hysterical Americanization of mores and media.

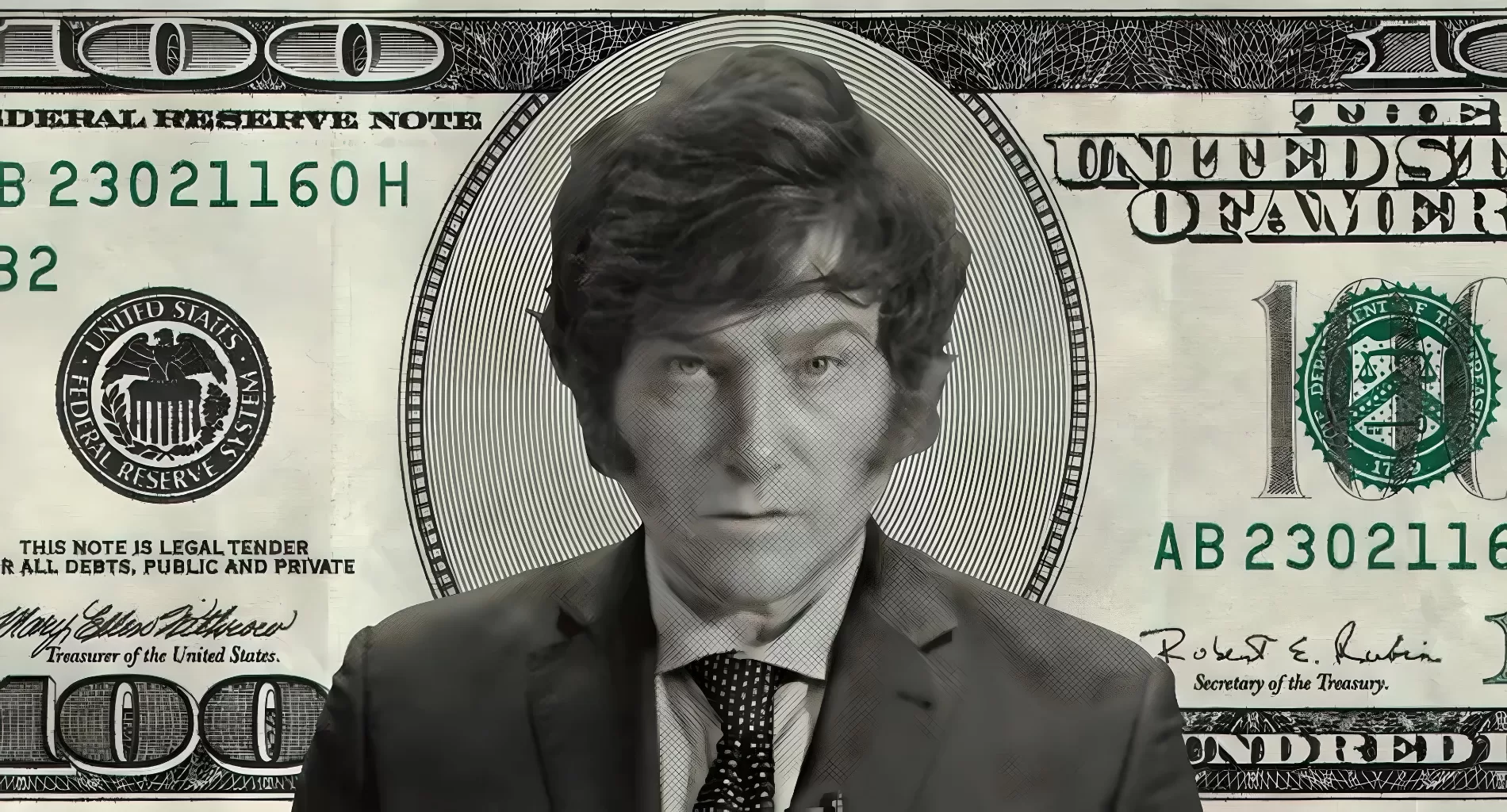

Now enters Milei, the winner of Argentina’s recent presidential election. The figure in question stands out for his mental fog and his cocaine charisma, not to mention his mixture of anarcho-capitalism and Zionism, an ideological blend that is becoming less and less exotic in the West. A bastard between Ayn Rand and Likud, presenting himself disguised as a Marvel superhero, the incumbent President Javier Milei is a symptom of the alienation produced by the galloping hyperinflationary environment. Nothing about him seems peculiar to Argentine political culture, and indeed Milei himself poses as an outsider, a player coming to kick the chessboard. Yet the portrait is quite false. Rather, Milei intends to prolong the free-trade jihad of former President Macri, himself a Marrano, although the irreverent and carnivalesque Milei currently adds the extravaganza of twisting Argentina’s diplomacy from a neutralist position to the neocon chorus line.

The change of rudder promises to fracture the BRICS project, while offering a protective rearguard for global Zionism. Likewise, Atlantic finance will have, now more than ever, carte blanche to plunder the local economy to the bone. Ominous precedent: only a decade ago there was the judicial seizure of the Argentine navy’s star frigate (2012) by vulture hedge-funder Paul Singer, who, anecdotally, bankrolls the gay proselytism throughout the hemisphere. As for Milei’s campaign financing, this mostly corresponds to diasporic minorities within Argentina, in particular Eduardo Eunerkian, the country’s fourth-largest billionaire. Predictably, the mercenary influences in Milei’s election will be made to pay their campaign contributions in due course, which means added pressure for the delirious privatization schedule.