The possibility of Eurasian integration or even cooperation has always been a threat to the Atlantic superpowers, in particular Great Britain and the United States.

Halford John Mackinder (1861-1947) was a British geographer, liberal politician and academic, as well as a member of the London School of Economics and the Royal Geographical Society.

He was also an arch-reactionary imperialist and served as High Commissioner to Southern Russia during the Russian Civil War and the British invasion of Russian soil, which he fervently promoted and supported.

Halford Mackinder is often considered the founder of geopolitics as an academic discipline. In 1904, Mackinder wrote The Geographical Pivot of History, in which he first posited the Heartland theory, which later would be used and adapted by people such as Nicholas Spykman. In his work, Halford Mackinder divided the world into three major areas:

- The World-Island: the vast landmass of Afro-Eurasia, composing the absolute majority of the world’s population, resources and territory, and the core of human history;

- The Offshore Islands, including the British Isles and Japan;

- The Outlying Islands: all areas more remote from the World-Island, including the entire continent of America and Oceania.

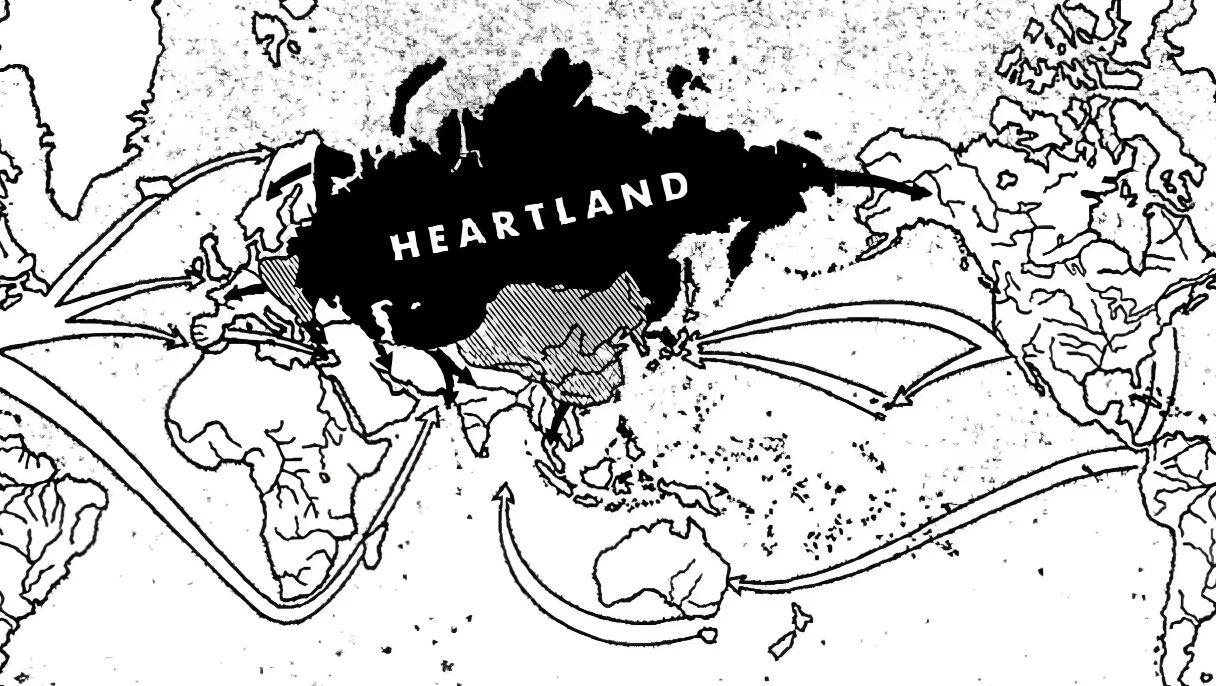

Within the World-Island itself, Mackinder further subdivided the territory roughly between the so-called Heartland and the Inner Crescent.

The Heartland, also known as the Pivot Area, is the absolute centre of the World-Island and, therefore, in many ways of the world itself. The Heartland stretches roughly from the Volga to the Yangtze and from the Himalayas to the Arctic. The area immediately beyond the very heart of Eurasia, which, as you may have guessed, corresponds largely to the area of Russia, was called the Inner or Marginal Crescent and is similar to Spykman’s Rimland, whereas the aforementioned Outlying Islands (including Britain and all of America) were also named the Outer or Insular Crescent.

Now, the interesting part is that both the Briton Mackinder and the American Spykman place their own countries, the old British Empire and the newly arising United States of America, respectively, at the periphery of world history. They know and admit that the Eurocentric view of history is complete nonsense and that their imperial homelands are, and always have been, at the sidelines of where world history is made.

So the question presented itself to Mackinder: how can countries like Great Britain properly position themselves as world powers for the future? Interesting here is that the main enemy of Britain, and the main threat to British domination in Mackinder’s work was Russia, even back in 1904 when the Russian Empire still had the tsar in charge.

The dyed-in-the-wool imperialist laid out a few options for what could happen in the Heartland in the near future:

- A Russo-German alliance was a horror scenario for British political leaders, in particular in the run-up to World War One. The fear existed that the so-called “autocratic” governments of Russia and Germany would join forces against the “democratic” West, combining Russia’s vast population and natural resources with the military might of the German Empire. Sowing discord between Berlin and Moscow, therefore, became one of Britain’s prime objectives in the early 20th century;

- Invasion of the Heartland by a Western power, with Germany being considered the ideal frontline attacker to be aimed at destroying Russia;

- Conquest of Russia by a Sino-Japanese Empire (possibly referring to the rise of Japan in the time period).

Control over Eastern Europe was seen as pivotal when trying to stem the rise of Russia as a major power, and Mackinder argued for the establishment of buffer states to basically act on behalf of Western powers against both Russia and Germany. “Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland; who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island; who rules the World-Island commands the world.”

Even in tsarist times, when Russia was ruled by family members of the British royal dynasty, Russia was already considered a threat, an enemy and an obstacle on the path to Anglo-Saxon world domination. This idea still permeates and continues to dominate Anglo-American policy in regard to Russia to this very day.