When life itself seems lunatic, who knows where madness lies? Perhaps to be too practical is madness. To surrender dreams — this may be madness. Too much sanity may be madness — and maddest of all: to see life as it is, and not as it should be!

— Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, Don Quixote

One of the great artistic struggles of the twenty-first century has been to capture our modern existence as “internet natives” in a way that is not poisonously self-referential, politically didactic, or mind-numbingly boring. That final hurdle, to capture the tediousness of lives largely spent tapping away at plastic keyboards and touchscreens while simultaneously still appealing to our human spirits, which long for the stuff of heroes, is no small feat. This is one of the reasons why our media landscape appears to be obsessed with the pre-internet past — it’s simply easier to do; the styles of depicting pre-internet lifestyles have been mastered and explored across popular media for decades.

This is why I try to fete those few creatives who I see daring to capture the post-2014 zeitgeist, especially so when they succeed as Dan Baltic’s 2022 debut novel NUTCRANKR does.

NUTCRANKR performs well on all three of my criteria, with not a single sore-like blister of the “twitter-brain” mind virus blotching its prose, and being populated by a cast of characters who are extremely politically opinionated (the bulk of the story taking place in the contentiousness of 2017) without a single one of them delivering a stump speech or being proven the wiser by the end. But its greatest success is at the narrative point-of-view level, scene construction, and in a way that it weds the two to deliver constant comedic hits.

At a line-by-line level, each paragraph is a swift-flowing stream into a punchline. Not a page goes by without a well-crafted joke being worked up to. And the pacing is swift as befits a comedy, with consistent use of contrast between high and low language, recurring overly dramatic phrasing, and clever wordplay, such as when Spencer lusts after his married professor Nora (henceforth known as the Nora-blossom):

Spencer could sense the strain in Nora’s marriage embedded within her attempt at nonchalant good humor. Clearly, she was growing tired of this man and with adequate reason. When the Muse marries the scrivener, both are at a loss. What is the Muse to do with a man whose soul is impervious to inspiration? The Muse needs a man who is equipped for the creative voyage of the one who is always self-overcoming. The Muse needs the Übermensch. And this lawyer was, at best, only a mensch.

Our narrator and protagonist, Spencer Grunhauer, self-consciously thinks in the language of Homer, Spengler, and Cervantes, displaying an advanced vocabulary while stumbling over the most obvious of social cues. He is, in short, a sperg. A man incessantly waxing poetic and capable of rationalizing whatever position he finds himself in. In a sense, Spencer is the story; his style of thought is the message. In Ursula K. Le Guin’s essay “From Elfland to Poughkeepsie,” she makes the bold claim that “style” is the most essential stuff of storytelling, as opposed to the specific plot beats and tropes which people so often associate with fiction. To quote Le Guin:

Many readers, many critics, and most editors speak of style as if it were an ingredient of a book, like the sugar in a cake, or something added onto the book, like the frosting on the cake. The style, of course, is the book. If you remove the cake, all you have left is a recipe. If you remove the style, all you have left is the synopsis of the plot.

And while Le Guin applied this theory specifically to fantasy, as a call to celebrate and emulate the bolder writing styles of Lord Dunsany and Tolkien over the hum-drum 3rd person point-of-view fiction with standard diction, which had begun to grow in popularity even in the 1970s, I would argue that this need for style is a universal one across all literary genres, and that the application of style in contemporary fiction such as NUTCRANKR is what defines it as a successful attempt to capture the spirit of the post-2014 era.

A Flat Earth Trapped in a Cube

The style elements of NUTCRANKR enable comedy primarily through the careful cultivation of irony. Irony has become something of a target amongst those aware of our modern predicament, but the often unstated gap between expectation and the actualized in this case is done with great sincerity.

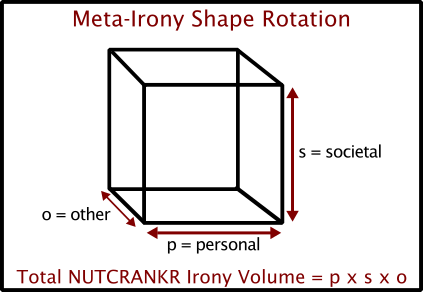

These contradictions operate on three dimensions: the personal (as experienced through our protagonist), the other (in the people Spencer attempts to connect with), and the societal (inescapable situations brought upon our players by outside forces).

At the personal level, Spencer’s personal mytho-poetic internal monologue clashes with his actual highly guarded and self-censored speech. He will in one moment write a political tract on the need for a government-enforced “Spousal Distribution System,” only to feign ignorance and even call his own material offensive when accused of authoring it. This ability to self-moderate betrays an elevated self-awareness despite his seeming purity as a sperg, as Spencer is able to self-censor and manipulate his language at times to comply with civilization without ever penetrating his own convictions, but his narrated reasoning always operates in this higher plane, even as his dialogue is largely reactive. Our narrator (like us) possesses a rich interiority which is unable to manifest in a healthy way due to social pressure and his own postmodern awareness.

But society as a whole, along with the other characters in the novel, are equally divided. The vaunted Nora-blossom, a professor at one of the most elite liberal arts universities in the country, who is tasked with educating the future elite, openly plays drinking games and verges on carousing with her students while her husband is out of town. The book’s love interest, Piglet, leads her romantic life with sexual acts on a fetish website while looking for true emotional affection and even a life partner. The corporate manager preaches team safety while emotionlessly taking away one of his staff’s livelihoods over an opinion expressed, without any offer at redemption.

This mass insanity reaches a crescendo at the 2017 Women’s March (better recalled by most as the Pussy-Hat Parade), which Spencer attends along with several other members of the fetish clique he finds himself a member of as a result of his romance with the Piglet. The mass of contradictions, mixed with Spencer’s own lack of social awareness, results in a critical mass of second-hand cringe, which is unacknowledged and thus left to weigh on the reader in a skin-crawling but highly entertaining way.

This is cringe as tragedy; world circumstances and character flaws doom the budding romance of Spencer and his Piglet, and Spencer’s very person as a result of his unquenchable longing for the heroic. Like all of us, Spencer Grunhauer is a man of a socially flattened earth, only beginning to realize how long ago all of Chesterton’s fences have been stomped and left to rot under the ground and leaving us all in a borderless hell. The entire framework for courtship, higher learning, and professional careerism were decimated decades before Spencer became a man, and his spiritual desire lacks anything concrete or genuinely sacred which it can even respond to in order to give himself a sense of place within the world.

And so Spencer’s superego dissolves into the ether of the internet. After the fated tragic conclusion of his romance with Piglet, he devotes himself entirely to “The Project” of creating the perfect theoretical political system in his online writings. Lacking any connection to the world, he spirals into plans to commit mass violence until he is foiled again both by his own deeper kindness, which compels him to pull back from the brink, along with his own inability to understand human reactions. Unfortunately, the legal system does not take self-realization into account, and Spencer is forced to spend several years in prison.

However, freedom does come eventually, and at the novel’s denouement Spencer has mastered the ability to live in two worlds at once. His interior enchantment persists even as he winks to the audience by describing the world in the same majestic and politically incorrect terms even as on the exterior he has completely integrated into modernity to such a level that he has become a celebrity as a recovered “extremist”. It is a sort of final angle upon the carefully constructed lattice-work of irony, stating that in order to live an enchanted life in modernity one must completely contain one’s own heroic inner-self and very carefully moderate the way it manifests in order to produce realizable gains in our fallen world. It is a lesson, however humorously it is delivered, that many of us have grappled with over the past several years.