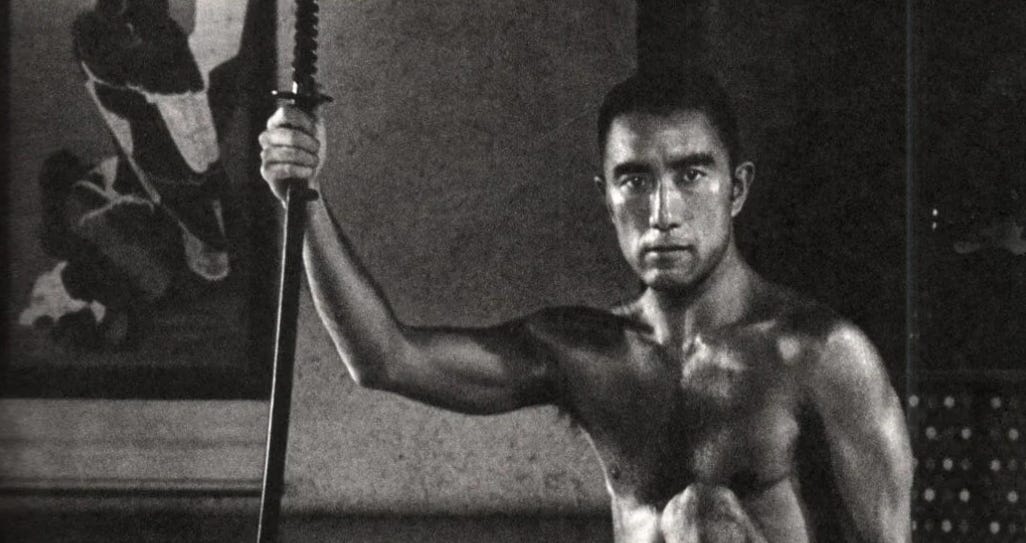

In our final article for Arktos Journal from the series dedicated to the comments of the Japanese writer Yukio Mishima on the classic samurai treatise Hagakure (‘Hidden by the Leaves’) (葉隱), we will consider the most important topic of this work — the theme of life and death, and how death gives life special meaning, as well as its final value.

Turning to this reasoning, Mishima points out:

Books One and Two, which expound the teachings of Jōchō himself, are replete with contradictions, and sometimes it may seem to the reader that one saying refutes the other. So, after the most famous words of Hagakure, “I have found that the Way of the Samurai is death”, we encounter a saying that at first glance contradicts them, but in reality only strengthens them: “Truly, a person’s life lasts for a moment, so live and do what you want. It is stupid to live in this dream-like world, face trouble every day and do only what you do not like”.

In this case, the words “I have found that the Way of the Samurai is death” is a prerequisite for reasoning, whereas the principle “Truly, a person’s life lasts for a moment, so live and do what you want” is his conclusion. In this case, the conclusion follows from the premise, but at the same time it goes beyond it. Here the paradoxical philosophy of Hagakure is manifested, where life and death are written on two sides of the same shield.

In an either-or situation, Jōchō recommends that we choose death without delay, but elsewhere he tells us that we should always think about what will happen in fifteen years. Foresight helps a person to become a good samurai in fifteen years, and then fifteen years will fly by like one short dream. On a cursory examination, these statements may also seem contradictory, but in reality, Jōchō simply does not respect time. Time changes people; it makes them calculating and forces them to retract their words. Most often, time worsens a person’s character and only very rarely improves it. But if we accept that each of us is constantly on the verge of death, and that there is no other truth except that which happens from moment to moment, the duration of the time interval will not seem very important to us. Since time turns out to be insignificant, a person lives for fifteen years as a single moment, and considers every day his last.

Thus, Mishima aptly notes that life and death in the philosophy of Hagakure are closely interrelated. Death and the thought of it are not obstacles to the flow of life; on the contrary, they are a condition and guarantee of its productivity. The realisation that you can die at any moment should not prevent you from making plans for self-improvement and your own achievements for fifteen years and longer. This may seem paradoxical at first, but this rule promotes maximum clarity of consciousness, which, as we remember from the philosophy of action, should always be in the present moment, and not ‘fall’ into the past or the future — into what has already happened and into what has not yet happened. This wisdom of Hagakure is extremely relevant for the modern world, which is overflowing with information viruses and value distortions, provoking a huge amount of ‘interference’ that prevents a person from being ‘in the present moment’.

Life according to Hagakure should be filled with a number of virtues. They are not explicitly codified in the treatise, however. Following Mishima, we can follow Jōchō’s thought and highlight the key aspects of the philosophy of life.

Life should be energetic. Mishima points out the following:

Hagakure extols such a virtue as modesty, but at the same time reminds us that a person’s energy of self-love allows him to act in accordance with the physical laws of the universe. There is no such thing as “too much energy”. When the lion rushes at full speed, the field disappears under it. Chasing prey, he can run through the entire field and not notice it. Why? Because he is a lion. Jōchō saw that man has a similar source of motivating power. If you limit your life to modesty, the daily activities of a samurai will not achieve a high ideal. This once again confirms the principle that a person should have a great conceit. He must be fully aware of his responsibility for the welfare of the clan. Like the ancient Greeks, Jōchō knew the charm and majestic radiance of what they called hubris (ὕβρις, pride).

In fact, this aspect is typical not only for Hagakure, but also for all other samurai treatises of this period. This is the morality of proud people who reinforce their position and attitude with an endless stream of energetic deeds.

Life should be devoted to caring and service. Mishima reveals this thesis as follows:

The human world is a world of caring for other people. Our social role is determined by this concern. Although the samurai era may seem cruel, samurai behaviour was based on much more subtle instincts then than in our time. Jōchō teaches that even when we criticise others, we should not forget about the virtue that is called “caring” or “participation”.

The concern Mishima is talking about here, of course, is primarily about specific people — family or clan members, close associates, but it can also be directed at a wider circle. Deep empathy of Hagakure is another aspect of the treatise, which, following the philosophy of love, is rarely noticed. Moreover, it may be completely invisible behind the variety of harsh theses on the topic of war, struggle and death. At the same time, it should be kept in mind that samurai morality is extremely specific; the empathy of Hagakure has nothing to do with modern ‘love for all mankind’, ‘striving for a world without wars’ and similar utopian semantic constructions.

Tolerance is necessary in life. Mishima notes:

In comparison with the strict, restrictive morality of Japanese Confucianism, Hagakure preaches tolerance. The philosophy of Hagakure emphasises the virtue of spontaneous actions and unwavering determination and has nothing to do with the thrift of the hostess, who carefully looks into all corners of the chest in which the rice was stored. As an extreme manifestation of tolerance, Jōchō recommends consciously ignoring the shortcomings and missteps of servants. This philosophy of conscious non-interference has always lived in the hearts of the Japanese. It both contradicted and emphasised their pedantic frugality.

The tolerance of Hagakure, which Mishima writes about, also obviously has nothing to do with the modern idea of tolerance, which is mainly tolerance towards outright evil and distortions (and sometimes their exaltation). Here we are talking about the creative side of tolerance — striving for perfection, as required by the Way of the Samurai, one should deign to perceive the imperfections of others. Such an ethical position allows you to simultaneously maintain balance when encountering distortions, but at the same time not to confuse the high with the low, the beautiful with the ugly, and the worthy with the unworthy.

In life, you need to be sincere in your relationships with people. In this regard, Mishima points out:

The tolerance that Hagakure talks about also teaches us that sincerity is an important part of human relationships. This opinion is accepted without objection even today.

The value of sincerity, emphasised by Mishima, is of course perceived as such in the modern world — at least in interpersonal relationships.

In life, it is necessary not to give in to despair. ‘Those who despair or lose heart in the face of failure are not fit for anything’, claims the Hagakure. ‘Therefore, do not get lost if luck is not on your side’, adds Yukio Mishima, and this is extremely important advice for life. Often the despair we feel when faced with the many manifestations of the crisis of the modern world can prompt us to give up. This should never be done. Martial arts master Kanō Jigorō said: ‘Fall down seven times, get up eight.’

Life should be spiritual. Mishima cites the following quote from Jōchō in confirmation of this thesis:

Although they say that the gods turn away from filth, I have my own opinion on this. I never neglect my daily prayers. Even if I have stained myself with blood in battle or have to step over corpses on the battlefield, I believe in the efficacy of invoking the gods with requests for victory and a long life. If the gods do not hear my prayers just because I am defiled with blood, I am convinced that there is nothing I can do about it and therefore I continue to pray, regardless of the defilement.

The spiritual optics of Jōchō are interesting because, despite the deep anti-materialism, the teaching of Hagakure is not dogmatic in terms of spiritual life. This is something that is sorely lacking in codified religions and spiritual teachings that have reached our time. Jōchō basically says: ‘I am a warrior, and I have to kill; this is the order of things, and there is nothing I can do about it.’ However, this is not a reason to abandon the inner spiritual work that should always accompany our deeds and thoughts.

All the principles of the Hagakure philosophy of life listed above, carefully conceptualised by us by Yukio Mishima, are shaded in the famous treatise by the principles of correct death, which are much more well known to the general reader. We have already pointed out the essence of this relationship above — thinking about death helps to live a better life. To illustrate this thesis, let us turn to what Mishima says about that. ‘I have found that the Way of the Samurai is death. In an either-or situation, choose death without hesitation’ is the most famous saying of Hagakure. Mishima comments on this as follows:

The Japanese are people who, at the core of their daily lives, are always aware of death. The Japanese ideal of death is clear and simple, and in this sense it differs from the disgusting, terrible death as it is seen by Westerners. The medieval European depiction of death is Father Time, who holds a scythe in his hands. Such images have never attracted the Japanese. The Japanese ideal of death also differs from the ideal of a country like Mexico, in whose cities, on abandoned streets, you can still see the dead ruins of Aztec and Toltec temples overgrown with lush greenery. Japanese art is enriched not by a cruel and savage death, but rather by death from under the terrifying mask of which a spring of pure water flows. This key gives rise to many streams that carry their clean water into our world.

What Mishima writes about is close to the ancient Roman imperative memento mori — even the triumphators were regularly reminded that they were just men, and all men are mortal. ‘Death for Jōchō has the strangeness, clarity and freshness of the azure sky in the gap between the clouds. In modern interpretation, this death is surprisingly consonant with the image of a kamikaze pilot during World War II. However, nowadays it is considered that the death of these people was perhaps the greatest tragedy of the last war’, Mishima additionally comments.

At the same time, the Hagakure philosophy of death is closely linked to the philosophy of action. The Japanese writer recalls that ‘according to Hagakure, the main thing in life is purity of action. Jōchō emphasises the importance of high passion and approves of death as a result of a passionate impulse. That is what he means when he says that only the faint-hearted can talk about dying in vain.’

Hagakure also claims that ‘we all want to live, and therefore it is not surprising that everyone is trying to find an excuse not to die’. Mishima comments on this thesis as follows:

A person can always find some excuse for himself. He has to invent some theory just because he lives and thinks. In this case, Hagakure simply expresses a relative point of view, according to which, having not achieved the goal, it is not worth continuing to live — it is better to die. Hagakure does not say that when a person dies, he thereby achieves the goal. This shows the nihilism of Jōchō Yamamoto, but this nihilism gives rise to the most sublime idealism. We are subject to the illusion that we are capable of dying in the name of faith or ideology. Meanwhile, Hagakure argues that even a senseless death — a death that brought neither flowers nor fruits — has the dignity of Human Death.

The Hagakure nyūmon final phrase sheds light on the deep connection between the philosophy of life and the philosophy of death in the famous treatise: ‘If we value the dignity of life so highly, how can we not appreciate the dignity of death? No one dies in vain.’

Mishima’s last phrase — ‘No one dies in vain’ — embodies the result of his extensive reflection on the ancient samurai treatise. In fact, it hides a constructive and creative position, which conceals getting rid of the main enemy of the human soul — fear. It is no secret that the fear of death is the ultimate fear of a human being. If we get along with the idea that in any case ‘we do not die in vain’, but at the same time we keep in our hearts those precepts of a good life that Jōchō gave, we live every day as our last, and at the same time strive for maximum perfection in everything we do every second, then our human experience and our very being is revealed to us from a different side.