In Upper Swabia, in southwestern Germany, there is an ancient village called Wilflingen, known since medieval times. It is situated away from major population centers, and even today, it is difficult to reach by public transport. On the outskirts of the village stands the family castle of the ancient von Stauffenberg lineage. Notably, Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s novel Castle to Castle takes place between the castles of Wilflingen and Sigmaringen, which are about twelve kilometers apart. In 1728, just outside the castle gates, a two-story baroque forester’s house was built by order of its owner. Strong, solid, with thick walls, thoroughly German in its sturdiness, it stands in the same place to this day.

Ernst Jünger’s house in Wilflingen

In the spring of 1951, at the invitation of Friedrich von Stauffenberg (a distant relative of Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg), the writer Ernst Jünger, along with his wife Gretha, moved into this house. Before that, the couple had spent nearly a year in the castle itself. This old house became a reliable refuge for Jünger, where he would live for almost 47 years until his death in 1998. A significant part of the German writer’s works is also connected with this place. It seems no coincidence that Jünger moved to this secluded corner in the same year his post-war manifesto The Forest Passage was published, which outlined the key trajectories of his later works, tied to the possibility of attaining freedom in the face of the ever-growing influence of the Leviathan.

In Wilflingen, Jünger lived according to a strict routine. Every morning, until a very old age, he would take an ice bath. He took long walks, observing the local fauna (he was particularly interested in ant colonies), and engaged in what he called “subtle hunting” — his term for his entomological pursuits. He was also a regular at the local inn Gasthof zum Löwen. In one interview, Jünger was told that due to his remote residence some considered him to be almost a sociophobe. The writer only smiled and suggested asking the local farmers what they thought of that idea. Rural life did not imply withdrawing from active work — Jünger maintained an extensive correspondence and received guests and journalists. His last interview, with Swedish admirers of his work, was recorded when the patriarch of Wilflingen was over 100 years old. The journalists brought Jünger a gift — a first edition of Carl Linnaeus’ Systema Naturae from the 18th century. He appreciated the gesture and decided to meet with them.

Inside Ernst Jünger’s house

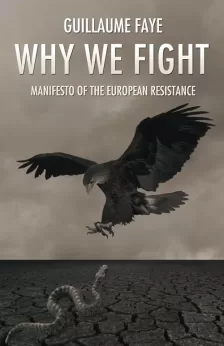

Jünger the bibliophile is a subject for a separate study. Books were one of the German writer’s collecting passions. They were literally everywhere in the house — about 15,000 volumes (today, the Jünger house museum contains 10,000 volumes; part of Jünger’s library, mostly inscribed books, was taken by the Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach). He hunted for rarities and bought entire collections. Johann Georg Hamann, Léon Bloy, Plato, Gottfried Benn, Herodotus, Catullus, Juvenal, Ovid, Publius Terentius Afer, Lucian, Kierkegaard, Alfred Kubin, Picasso, Maurice Barrès, Gómez Dávila… Simply listing the authors who sustained Jünger’s interest would take considerable time. His entomological literature occupies a large separate shelf. In 1933, after the Nazis came to power, on his way to “internal exile,” Jünger purchased 79 volumes of the works of the Church Fathers. “As always, books remain a consolation — these light little vessels for journeys through time and space and beyond. As long as there is a book at hand and time to read, the situation cannot be hopeless, completely unfree,” Jünger wrote in his diary after the war.

Bookshelves in Ernst Jünger’s house

Aside from books, Jünger collected beetles (he gathered all the species found in Europe), walking sticks, mollusk shells, butterflies, minerals, hourglasses, and many other things. His entire house resembled a cabinet of curiosities. There was no shortage of curiosities. Jünger saw collecting as a unique form of translating military order into a peaceful setting. Trinkets from numerous travels and souvenirs he received as gifts decorated the bookshelves and walls of the house. Paintings by Rudolf Schlichter and Alfred Kubin hung in the rooms, along with a bust of Jünger, created by another German centenarian — sculptor Arno Breker.

Ernst Jünger’s beetle collection

Jünger had a particular interest in shipwrecks and mutinies (he began exploring the topic in 1944), and his office even featured a model of the legendary ship Bounty, famous for one of the most well-known mutinies in maritime history. It is worth recalling that the ship became a central symbol in The Forest Passage. In the 17th chapter, he writes, “[t]he ship signified the temporal, while the forest represents timeless existence.” This metaphor first appears in his diaries at the very end of the war: “The ship represents order, the state, status. During a shipwreck, with the breaking of planks, these ties disintegrate, and human relationships descend to an elemental level. They become physical, zoological, or cannibalistic.”

Model of the ‘Bounty’

Among other collectible items, it is interesting to note small household objects Jünger found during his long walks in the woods: hairpins, nails, paperclips, pencils, and other small trinkets. He would bring them home and place them in a separate vase, a side effect of his extraordinary observational skills. Near this, on the bathroom door, hung numerous bright “Do Not Disturb” signs in different languages that he had brought back from hotels where he stayed during his travels.

Bathroom door

Jünger could not stand plastic products and did not acknowledge the material, with the exception of adhesive tape, which he considered a wonderful invention. He used it eagerly to make inserts in his notes.

In 1960, tragedy knocked on Jünger’s door. After a prolonged and serious illness, his wife Gretha, “Perpetua” as Jünger called her in his diaries, passed away. (In 1962, Jünger would marry his second wife, Liselotte Lohrer.) He cherished her memory throughout his life. The bathroom in the house is decorated in pink, Gretha’s favorite color. In one room, there is a touching painting that recalls the first meeting of Ernst and Gretha. Its creator is none other than poet and painter Hans Leip, the composer of the song “Lili Marleen.” The painting is complemented by handwritten lines from one of Longfellow’s poems:

Ships that pass in the night, and speak each other in passing,

Only a signal shown and a distant voice in the darkness;

So on the ocean of life we pass and speak one another,

Only a look and a voice, then darkness again and a silence.

We have already mentioned that Jünger loved and collected hourglasses. As he himself noted, they helped him tangibly feel the flow of time. However, he could not stand the ticking of mechanical clocks and kept his alarm clock sealed in its Styrofoam packaging to muffle the sound as much as possible.

Ernst Jünger’s collection of hourglasses

One of the rooms in the house had a television, though it was not watched often. Next to it, the German writer kept an opium pipe. In his last interview, Jünger was asked if he had mastered computers yet, to which he responded, “The encounter of the human mind with a machine is uninteresting. Intoxication is far more captivating.”

Much of what is described in this article was learned thanks to the caretakers of Jünger’s house museum, which was opened in the forester’s house in Wilflingen in 2011 through the efforts of the Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach, the Ernst Jünger Foundation, and the circle of friends of Ernst and Friedrich Georg Jünger. The house retains the unique atmosphere of the great German writer’s abode, with every detail in its place. On the table stands an ashtray, and next to it, a pack of Dunhill. It seems as if the owner has just stepped out into the garden and will return any moment.

Somewhere in the garden, by the way, Jünger’s turtle, named Hebe after the Greek goddess of eternal youth, still lives to this day.