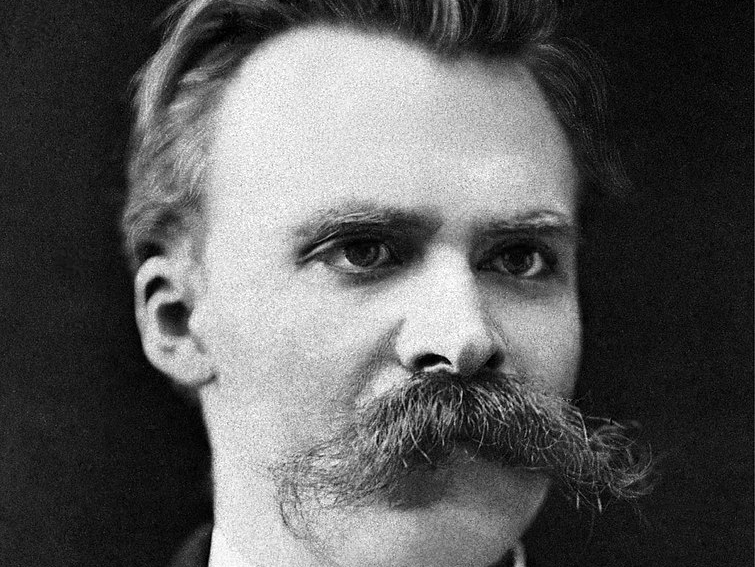

“I am not a man, I am dynamite,” wrote Friedrich Nietzsche about himself in his work Ecce Homo, composed in 1888 — just before the onset of his mental breakdown. What sounds immodest certainly contains a kernel of truth.

Until 1945, Friedrich Nietzsche exerted a tremendous influence on a wide range of fields such as politics, music, visual arts, literature, and philosophy. The poet and essayist Gottfried Benn described him as the “greatest phenomenon of influence in the history of thought.” Friedrich Nietzsche was born on 15 October 1844, in Röcken near Leipzig and came from a family of Protestant pastors.

He was considered a child prodigy and, at the age of 26, was appointed a professor at the University of Basel before completing his studies in theology and ancient languages at Bonn and Leipzig. There, the historian Jacob Burckhardt, whom Nietzsche greatly admired, taught.

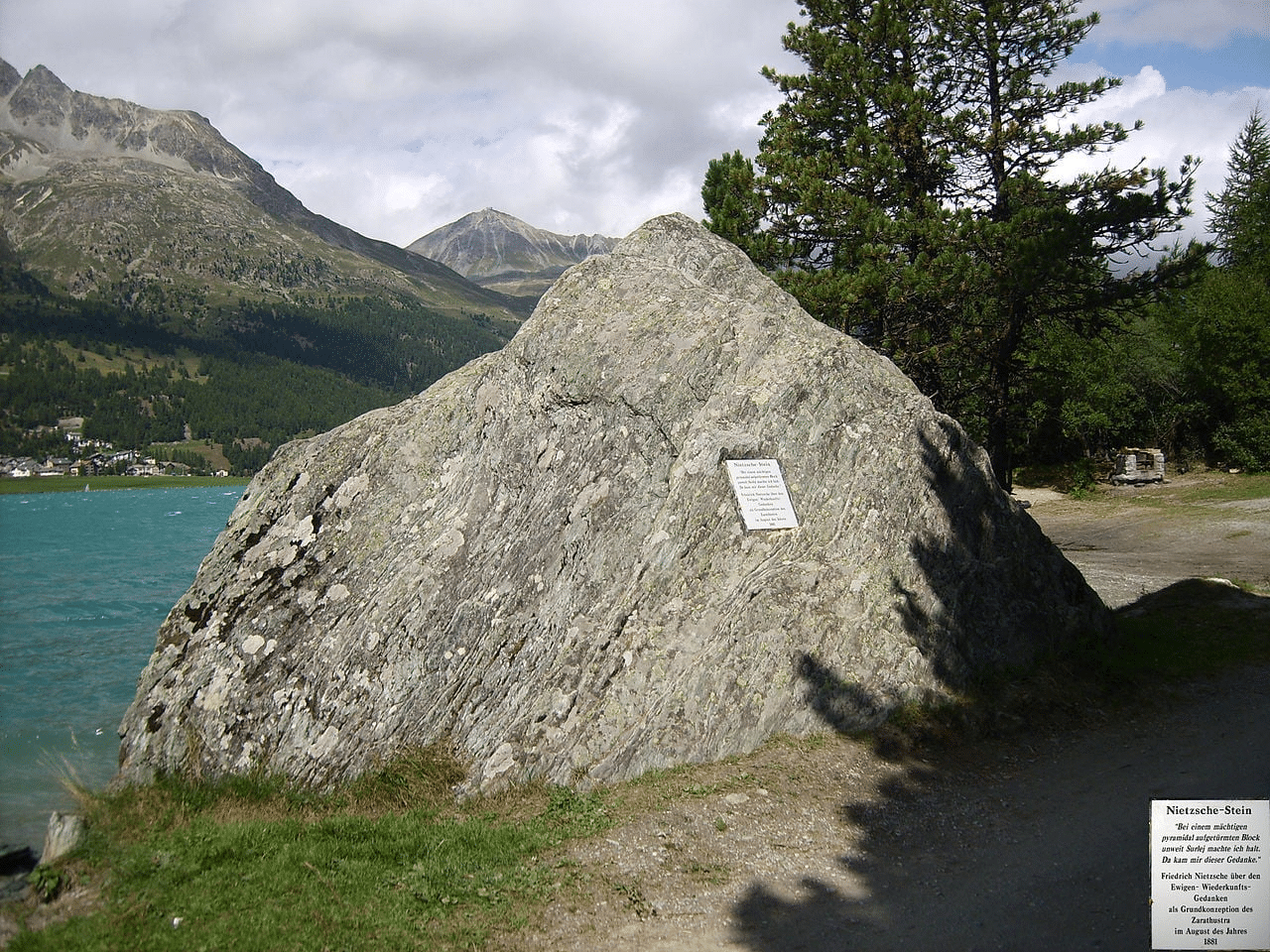

The Nietzsche stone near Surlej in Upper Engadine. According to Nietzsche, the stone inspired him in 1881 to develop the core concept of ‘Thus Spoke Zarathustra’.

In 1872, his first major work, The Birth of Tragedy out of the Spirit of Music, was published, in which he interpreted Greek antiquity through the interplay of the Apollonian and the Dionysian. Nietzsche expressed his hope that the composer Richard Wagner could succeed in fostering a rebirth of Hellenism through the German spirit. However, Nietzsche primarily looked up to the pre-Socratic era of ancient Greece between Homer and the Persian Wars, with its agonistic and pre-democratic culture deeply rooted in myth. He regarded the pre-Socratic Heraclitus as one of his philosophical “ancestors,” whose thoughts led to the core of Nietzsche’s own. The world is understood as a purposeless conflict of forces. He particularly highlighted one fragment of Heraclitus: the world is “the game of a child: a becoming and passing away, a building and destroying without moral accountability.”

A Rebirth of Hellenism through the German Spirit?

In 1879, he gave up his professorship in Basel due to persistent headaches and eye pain and led a wandering scholarly life in Germany, Italy, and Switzerland. During this period, works such as Dawn (1881) and The Joyful Science (1882) were written. These works, following in the footsteps of the Florentine thinker Niccolò Machiavelli, whom Nietzsche greatly admired, focus particularly on exposing and unmasking the charade of the so-called “good people,” who primarily invoke morality to expand their own power.

Nietzsche as the “Physician of Culture”

His later works include titles such as Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883–85) and The Antichrist (1888). Nietzsche was now concerned with “great politics” and did not shy away from terms like “breeding,” “Übermensch,” and “will to power.” He saw himself as a “physician of culture” who wanted to cultivate free, courageous people devoted to immaterial values, those who would prioritize their quest for knowledge over a comfortable life. On 25 August 1900, the great aphorist passed away in Weimar. His influence will continue well into the 21st century, as he foresaw many things more clearly than any other thinker of the 19th century.

(Translated from the German by Constantin von Hoffmeister)

This article was originally published here.

Purchase Alfred Baeumler’s Nietzsche: Philosopher and Politician here.