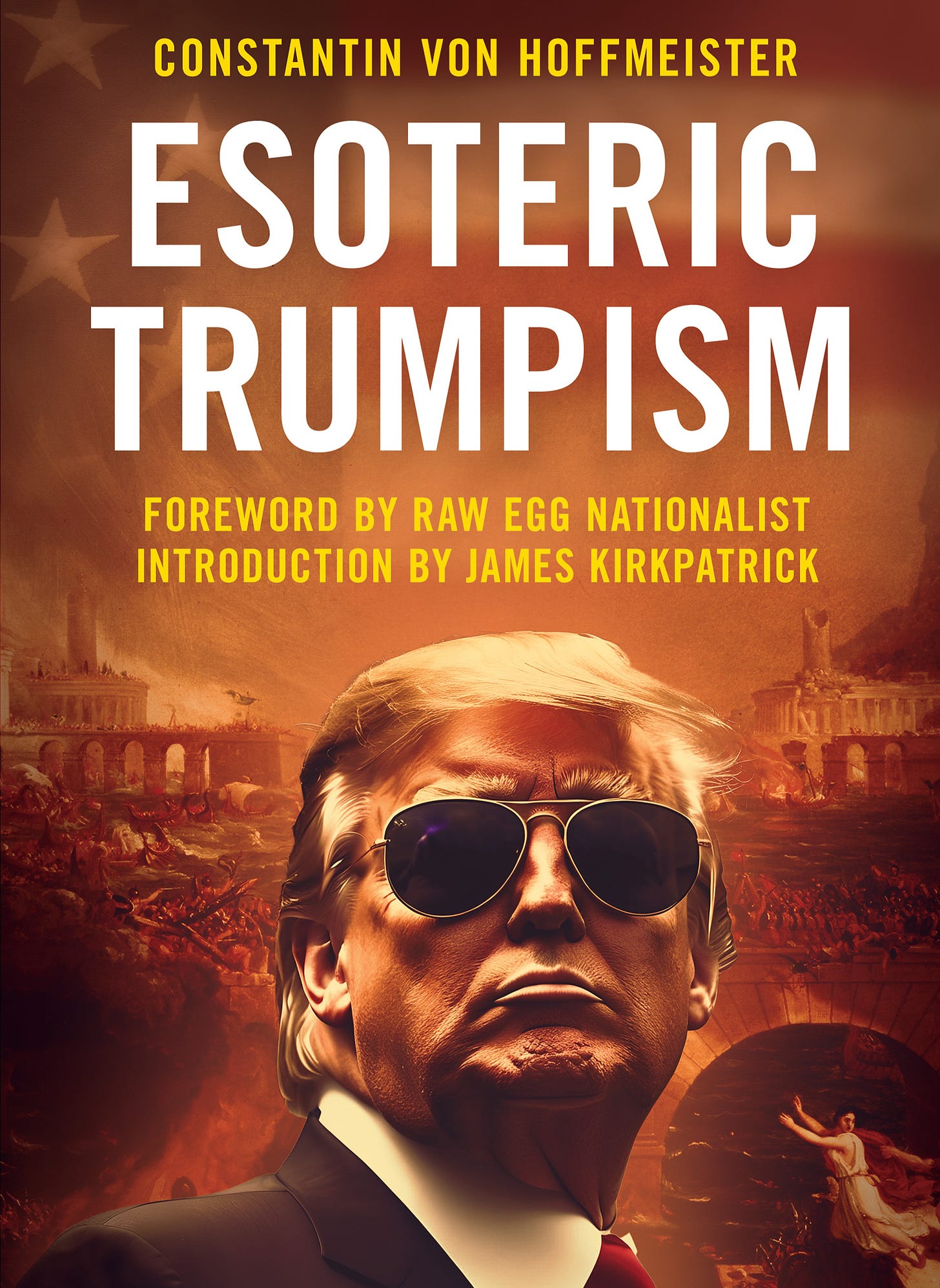

Esoteric Trumpism. The title of Constantin von Hoffmeister’s book hints at a particular direction. The term “Esoteric Trumpism,” derived from “Esoteric Hitlerism” by figures like Miguel Serrano, Savitri Devi, and Hakun Zynkyoku, is often used as a catch-all for certain occult memes and theories popular within segments of the U.S. right wing. Examples include the concept of the meme as a sigil to channel occult powers into an idea, the Egyptian chaos god Kek as the true identity of the frog mascot Pepe, the NPC as a modern rendition of the soulless hyle from Christian Gnosticism, the coincidence that “Donald” means “ruler of the earth” in ancient Celtic, the fact that a 19th-century American author named Ingersoll Lockwood wrote books about a “Baron Trump” who ventures to the North Pole, explores a hollow Earth, and discovers humanity’s origins, as well as a book about a “controversial outsider” who unexpectedly becomes U.S. president and incites violent leftist protests, etc. However, this book is neither a review nor a supplement to this meme culture; it relates more to European right-wing thought than to meme esotericism.

One meme, however, does feature prominently in the book: there are chapters dealing with Trump’s relation to “German Idealism.” This connection refers to an interview where a journalist spoke to an online activist named “Kantbot,” who excitedly declared that Trump would complete the philosophy of “German Idealism” (Hegel, Fichte, Schelling, etc.), unveil aliens, reveal the truth about human consciousness origins, and rediscover lost continents like Thule and Atlantis. This snippet from the interview became a meme. (Interestingly, during his tenure, Trump did attempt to purchase the Thule Air Base in Greenland on behalf of America, and in an interview with German journalist Alexander Markovics, Russian philosopher Alexander Dugin remarked that Trump supporters urgently needed to engage more with “German Idealism.”)

Constantin von Hoffmeister addresses how Trump would complete “German Idealism” in a rather straightforward manner, suggesting that Trump’s populism and patriotism highlight the American Volksgeist (national spirit) as part of the “World Spirit” while reconciling individual-based liberal values with the Hegelian State as an actor in both the national and world spirit. The author seems to view Trump as a Hegelian “world-historical individual,” embodying the spirit of the age and driving history forward.

In another chapter, Trump is compared to Oswald Spengler”s “Caesars,” figures akin to Hegel’s “world-historical individual,” who appear at the end of a cycle and encounter the onset of a new civilization. Many notable unifiers, such as Charlemagne in Europe, Qin Shi Huang in China, and Japanese unifier Oda Nobunaga, were considered Caesars in Spengler’s sense, as were figures like Napoleon Bonaparte, who emerged at the decline of an empire and enabled a new beginning.

The book’s two forewords already present an intriguing thought: both allude to the concept of archaic revival from the philosopher Terence McKenna. McKenna, a hippie, entheogen researcher, and mathematician, developed a philosophy well aligned with Traditionalism. It has two components: one positing that modernity aimed to create a scientific, rational world free of chaos, but that chaos has built up on the edge of the “ordered world” as entropy, eventually poised to overwhelm modern technological civilization (what Heidegger calls Gestell, or the “enframing”) like a flood. Alongside this theory, also known as “timewave zero,” an unnoticed “archaic revival” is occurring, where more pre-modern, traditional elements are re-entering society, initiating a return to tradition. The two forewords interpret Trump as one such element — a symbolic incarnation of an end-times king returning (like Barbarossa in Germany, King Arthur, “Chaka the Great Lion” among the Zulus, or the hidden 10th Imam in Islam) to guide humanity through the last phase of the great time cycle and into a new beginning. Interestingly, Julius Evola also occasionally referred to this archetype as the “God-Emperor,” a well-known nickname for Donald Trump. Constantin von Hoffmeister even describes Trump as a kind of reincarnation of George Washington in one chapter, further strengthening this perspective.

What is also interesting here is that John F. Kennedy was seen as a “new Arthur” in his time. Science-fiction author Philip K. Dick, known for works like Blade Runner and his occult philosophy, believed that Kennedy, Martin Luther King, and others were tasked with ending the cycle of time, guiding America back to religion and tradition, exposing a dark cabal of Satanic powers, and ushering in a new golden age where humanity would finally be freed from the “black iron prison” imposed on their minds by the power elite. (Similarly to how Trump’s followers also hope for such an outcome.)

Interestingly, Trump is working with Robert Kennedy, one of the last surviving members of the Kennedy clan, during his campaign and even intends to offer him a position.

The book’s initial chapters focus on Trump’s “drain the swamp” metaphor. Constantin von Hoffmeister identifies something that most commentators and Trump supporters were not consciously aware of. The term “swamp” carries a deeper meaning than merely a place of chaos, darkness, and hidden evil. (Recall 1950s b-movies like The Creature of the Black Lagoon featuring swamp monsters.) The book even draws a parallel to Lovecraft, whose demon gods often appeared near water. This thought is intriguing, as in fairy tales and mythology, water and forests were often portals to the “otherworld” (e.g., Hansel and Gretel and the wicked witch). Even Dante Alighieri, in his famous Divine Comedy, finds the entrance to Hell after getting lost in the forest. In Greek mythology, the threshold between the normal world and the world of myth and legend was often a river or sea that had to be crossed. The swamp combines both elements, but as Constantin von Hoffmeister points out, it also adds the element of “rotting.” Through this metaphor, Trump is positioned as a warrior destroying this chaotic “place of evil and disorder” to save America.

In the following chapter and beyond, it is described that Trump’s followers also see America’s current system as internally “rotten,” with examples of how the American system has betrayed its ideals, from election manipulation to undemocratic concentrations of power, to even Orwellian attempts by Netflix, among others, to rewrite world history according to left-liberal ideology. (Later, the author also references Alexander Dugin’s text “Liberalism 2.0,” where Dugin argued that the ideals of classical liberalism of the Austrian School have been corrupted and that today’s Democrats or Greens represent a bizarre caricature and total betrayal of true liberal values.) The author explains that this is precisely why Trump’s supporters are unfazed by the elite’s attempts to indict and demean him. Every effort by the system to belittle Trump only further solidifies his supporters’ belief in him. This chapter unavoidably evokes thoughts of Christ and how he was mocked, indicted, and tortured by the authorities of his time, echoing Christ’s famous quote, “Do not be troubled if the world hates you, for you are not of the world.”

This book is not a work of conspiracy theory. It does not attempt to explain who the “cabal” or “deep state” are, nor does it delve deeply into the development of liberalism. Instead, it uses flowery language to describe Donald Trump’s struggle. This gives the book a somewhat repetitive nature and makes it feel a bit sparse in information at the start. Often, the book doesn’t progress from one concept to another in a structured way. Certain themes repeatedly resurface, with the author intensively addressing the “swamp” metaphor, then moving on to other topics, only to return to the swamp later.

The book does not aim to make the reader more informed or knowledgeable but rather to convey a feeling. What sort of feeling? In a way, the book aims precisely to explain what Claremont University employee and later Trump advisor Michael Anton expressed in his essay “The Flight 93 Election”: that time is of the essence. The forces of evil have taken control of the American state and are treating it like terrorists with a hijacked airplane. Now is our last chance to stop the “terrorists,” regardless of the collateral damage. The battle is worth it.

However, while Michael Anton uses the metaphor of a hijacked plane, Constantin von Hoffmeister elevates the concept to an apocalyptic level. (Some of his metaphors explicitly draw from the biblical Book of Revelation.)

This gives the book a compelling quality, making it an enjoyable and easily readable experience.

It is striking that the author frequently uses water-related metaphors for both Trump’s opponents and his supporters. Traditionally, water is seen as a feminine element and an element of chaos. This metaphorical similarity is surprisingly fitting, as Trump’s supporters may verbally oppose the “forces of chaos,” yet they themselves are something of a literal “chaos troupe.” Their god, Kek, resides in the Tabula Rasa from the beginning of the world, and events like January 6 exude a highly chaotic aura.

Some chapter topics, such as “race” and “whiteness,” may seem unusual to European readers, who typically identify as Germans, French, or as part of “Christian Western civilization.” However, as America is a blend of various European and non-European migrations, this topic holds much more significance there than here, impacting both right-wing and “anti-racist” left-wing perspectives. Hence, the subject is indeed important.

The book touches on Oswald Spengler’s metaphor of the “Faustian” man. Like many modern right-wingers, the author uses it as a hymn to the European drive for exploration and the pursuit of “faster, higher, farther.” However, it misses the dual meaning Spengler evidently intended. After all, Faust is not known for his scientific achievements but for making a pact with the devil in the story. If the author views the archetype of Western civilization as a scientist who sells his soul to the devil, interesting questions arise about Trump, which the author unfortunately leaves unanswered. Trump’s supporters often view the Western elite as Satanic. Has the West, like Faust, quite literally sold its soul to the devil?

Constantin von Hoffmeister discusses Trump’s creation of a “Space Force.” While some QAnon followers interpreted this as Trump joining a secret war with U.S. “Men in Black” units against reptilian aliens, remnants of Nazi UFO fleets (called Nachtwaffen [Night Weapons]), and other entities, the author takes a much more grounded approach.

He suggests that Trump aims to rekindle America’s lost hope for a golden future. The author, similar to Mark Fisher, describes how the West has figuratively buried the concept of a future. (This is evident in Europe too. Nuclear power was once seen as a beacon of a golden age; Germany has dismantled its reactors. The Transrapid magnetic levitation train was scrapped by the “progressive” Greens. The legendary Concorde was retired, as was the American Space Shuttle. Instead, the elites envision a future where one can choose from billions of genders. What a future.) Constantin von Hoffmeister posits that Trump, through the Space Force, seeks to make a U-turn and return to the optimistic era of Buzz Aldrin, nuclear-powered cars, etc. Interestingly, Trump collaborates with Elon Musk, one of America’s last “futuristic” entrepreneurs, who operates his own space agency, SpaceX.

Later, the author portrays Trump as someone whose thoughts parallel Guillaume Faye’s concept of Archeofuturism. Roughly, Faye argued that striving for a distant future and returning to tradition are not, and must not be, contradictory, but should be united. Many American writers view science fiction, such as Dune, Star Wars, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, or Legend of the Galactic Heroes, as expressions of this Archeofuturism. The author sees Trump’s internet-driven influence and the renewed large-scale interest in thinkers like Evola among Trump supporters during his campaign as signs of Archeofuturism. Trump’s position as an entrepreneur is interpreted similarly. (It is worth noting that in the Austrian School, the market is essentially a massive competition to find the most efficient solution to a technical problem. This is why thinkers like Nick Land believe that the market drives machines to develop increasing intelligence.)

The book, like many American right-wing works, attempts to establish the thesis that Republicans and their supporters in states like Texas represent a tellurocratic, rural, warrior-like, and tradition-loving “land culture” (similar to how one might view Prussia, some Arab countries, and Japan), while the Democrats, with their coastal strongholds in states like New York and California, are seen as an embodiment of the thalassocratic sea-based civilization (materialistic, anti-traditional, and rootless or migratory). There is some evidence for this thesis (the Civil War is often cited as an example, and Texas is home to many people of Prussian descent), and certain points within this interpretation suddenly make more sense. For instance, the states representing a warrior culture also uphold the Second Amendment and the right to bear arms, which logically aligns with a “warrior” mentality.

However, it is important to note that the original creators of the land and sea thesis clearly classified liberals as thalassocrats and not as people of the land. On the other hand, Trump’s supporters seem to understand the position of other “land peoples,” like Russians and Hungarians, surprisingly well, while the mentality of sea peoples remains an endless enigma to them.

Trump supporter “Anonymous Conservative,” who developed the r/K selection theory — biologically based but with remarkable parallels to the land and sea thesis — categorizes libertarians as a marginal “third path” that does not align with either land or sea. This third path wants to disengage from conflict, live independently, and be left alone. Alexander Dugin has similarly described libertarians, Americans, and Russian anarchists in several texts. (The American, who, like in a John Ford Western, moves into the empty plains beyond the frontier so his death belongs to him alone, or the Russian Old Believer who, out of Christian devotion, “wants to belong to the world” and thus withdraws to the Siberian wilderness to avoid corruption — foreshadowing the anarchist commune, etc.) Therefore, it is possible that Trump’s followers are not tellurocrats but occupy this third position, or that Trump’s base is a mix of tellurocracy and this third path.

Overall, the book is very interesting, with many intriguing ideas. It is, broadly speaking, not a cerebral book that seeks to reveal eternal solar principles. Nor does it aim to be an in-depth analysis of Trump and his supporters. Instead, the book relies on a feminine, lunar intuition and sense of awe to convey to the reader the monumental, “biblical-scale” challenge Trump faces and the abyss he seeks to keep the world from falling into. As such, it reads more like a manifesto and a call to arms against the “Prince of this world” and his neoliberal followers. The reader is to understand that Trump might be the West’s last chance for rebirth.

Buy Esoteric Trumpism here.