Although I grew up in California, I was brought up by Nebraskans. My family has a long American lineage, with some ancestors dating back to early settlers on my father’s side. The most recent members of my family immigrated to America in the 1800s. My family originates from Virginia and were among the first settlers in Nebraska. They had a unique culture — rowdy, rough giants who would give you the shirt off their back if you needed it.

Family and extended family are deeply ingrained in Midwestern culture, so every year my grandparents would return to Nebraska for Thanksgiving and hunting season. I would often join them and these trips were an extension that contextualized my understanding of my family compared to their surroundings in California. Early life experiences have the greatest impact and generate the most cultural transmission, especially when surrounded by a close-knit extended family network like mine.

From the 1940s in Nebraska. My great uncles, grandpa and great aunt.

I am more Nebraskan than Californian, and the contrast between the two is and was very stark. My cousins had a wonderful community in a small-town upbringing that I envied. Though I had a closer family than most of my peers in California with my aunt and uncles and grandparents helping raise me, it was nowhere near as close to the level of extended family involvement that I experienced with second and third cousins and great aunts and uncles back there.

In hindsight, I now realize it was not old California culture that I was noticing the contrast with but a mechanized and consumptive anti-culture that infected different regions at varying rates. Everyone hates “California” as a place for blame in the United States, but usually that’s code for hating rich boomers or Mexicans or, in some cases, liberals. Most exodus from California is not economic in Gen X and younger generations, but white flight from dangerous conditions for families — be it third-world chaos or globalist indoctrination.

My great grandma Rose and my grandpa in the 1940s.

My grandmother was like the glue of our family and when she passed away unexpectedly when I was reaching adulthood, everyone moved away. My grandfather couldn’t bear to be on the West Coast as it reminded him of the love of his life that he lost since they moved there with their children to build a new home. He retreated into his extended family and moved back to Nebraska but for some reason I had an aversion to it that I’ve more recently realized was due to a lack of new life in our family line, making the loss of the old more bitter.

I only returned to Nebraska briefly in the last half of my life when I decided to take my children back to their ancestral towns to visit the dead. It is important to honor the connection and I could feel their bones in the dirt. This last trip was shocking to me because of how much it had changed. It had already been changing with demographic replacement when I was younger because ending unions allowed the meat-packing plants and corn industry to hire a lot of illegals. At that time, there was still what seemed to be a thriving Nebraskan community because, by comparison, I was used to being the only blonde child in my public school or one of a few white children in hostile conditions.

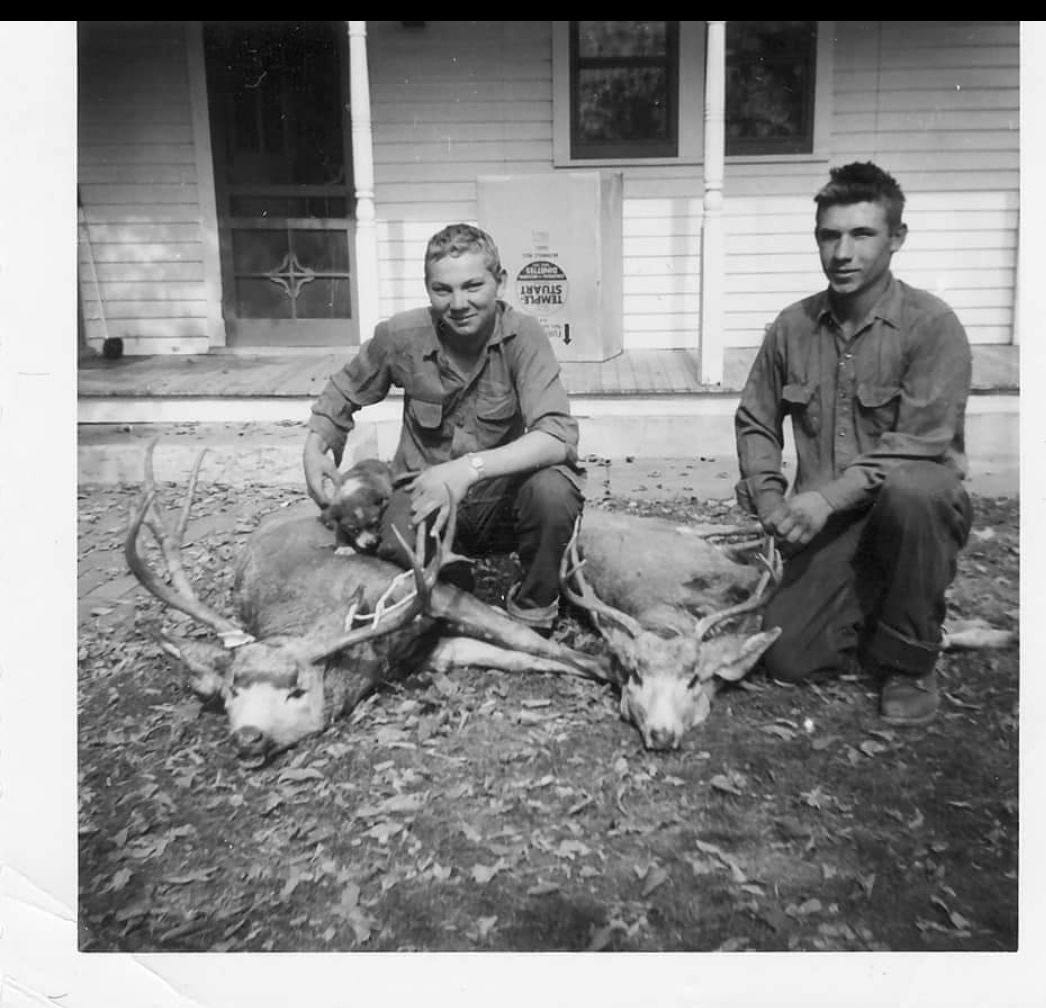

My grandpa and his cousin in the 1950s.

This last visit showed the end stages of what was already the decline when I was young. The small town was full of third- and developing-world migrants festering on a decaying corpse. Mom-and-pop shops closed up in what used to be a thriving, quaint downtown half a century to a century ago. The last remnants I saw as a child are now completely gone. The few stores in the town were big chains like an artificially upheld Frankenstein monster animating a long-dead body. The Whites that were there looked very depressed — with an aging population, a total loss of spirit and healthy pride.

I brought my children to the graves that I visited when young. The oldest ancestor’s gravestone I could find was from the mid-1800s. There was the feeling of irony that while honoring the dead, the surrounding towns were like a graveyard of their beautiful culture. Franken-stores contrasted with the beautiful abandoned houses and storefronts. The small farms had all been long consolidated into monocultures to the extent that there was no habitat left for the pheasants to live and be hunted wildly, or much any other game for that manner. Every negative space where life could thrive had fallen to use, so all that was left was the simulation of real hunting north of there on stocked, fancy land.

My grandma and grandpa in the 1950s.

Returning to our family cabin on the river I played in as a child was bittersweet. My children could not play in it since it is now so toxic and carcinogenic from the overuse of pesticides. I could hear the echoes of their laughter and memories all across the decaying town, going to look at old rundown homes that were built by my family and now house foreigners. I saw not only my own memories but the shadows of their stories from my mind’s eye in the empty, abandoned buildings.

I saw Africans and Mexicans and tons of police on almost every street. As a child it was rare to see them and decades before that my great uncle was the only sheriff for the entire county. But more than these more practical or logical shifts that everyone thinks we can reason ourselves back to was the haunting finality of cultural death. Police and laws can only slow the parasites, but they can’t bring the spark of life back. No White children were running between the neighboring homes of families that had known each other for generations. Now it has the culture of Walmart, McDonald’s, videogames, and some abstractions of the internet.

People all die; that is a part of life, but death is harder without new life. The death of a culture is more profound and final than the death of a person within it. If the culture still lived, I could go there and see those who reminded me of my grandmother, my father, my great uncle — not just their physical characteristics but also the mannerisms that animate them and shape their expressions, how they interact, their values, customs, and predictable insisting that you eat and drink when casually socializing. There was no longer the feeling of home there. The culture had died and all that was left was a zombie in its place.

Nowhere feels like home now; it’s as if it only exists somewhere in an unreachable past. Nebraskans have lost the feel of their own culture, and their younger generations are akin to boomers in the West. In its place (culture) is an empty lawfulness in regions with the slow encroachment of primitives and behavioral sink. It all feels very superficial and like an exchange. The lawfulness comes at the price of preventing meaningful action against the encroachment, the folkish spirit and community long replaced by convenience and a simulation of the forms of more urban and decadent old America. Everyone seems to enjoy the short reprieve, focusing on material distractions and vacations while aboard a slowly sinking ship.

There is something more profoundly haunting and final in this loss. As we drove back to the cabin where I spent many of my most cherished childhood memories, I half expected to see our old hunting dogs running up to greet us and extended family out visiting in the yard, but all that was left was their ghosts. My children will never experience the full culture of this place that nurtured me and I once loved; they will never know this place as I did. All that is left for them to see now are graves.

As the sun sets, a new dawn breaks. The new literary genre will be born from personal tales such as this. The Edith Whartons and Dosteyevskys of the current situation will come, and they will explain us to ourselves, and to our posterity.