A rightist outlook is necessarily bound up with a reverence for tradition, and though some would disagree, for the most part this means a sustained engagement with religion and its proper forms. The meme-summons to RETVRN begs the question — to what, exactly? The NormieCon will go so far as to embrace the Protestantism of two generations prior, those more rarified days when the smoke machine wasn’t so prominent in the musical numbers. But for the true right the inquiry must be broader and deeper.

So fractured is the contemporary religious landscape, such a sacking has liberalism given it, that a good portion of at least the online right have thrown up their hands and declared, as did their prophet Nietzsche, that God is dead, lost to the hearts of the sons and daughters of modernity. This is not a call for atheism, but rather for some great- and cold-hearted new man to impose a spiritual settlement befitting this age — but being rightist, necessarily informed by the past in some way. Building on this, some have taken cues from there and elsewhere to discard not only the religiosity of the recent past but any elements seen as contra-West and anti-white, a spirituality for a European man cleansed of supposed invasive Jewishness. The theory seems to go that this will reverse a decline that emerged at some unspecified point in the Western past whereby white men will recover the mentality of lusty archaic warlords while somehow also retaining the traits that make widespread consumer materialism possible. At any rate the boat people will be gone, so there’s that.

This generally manifests itself in one of three ways. The first is reconstructed paganism, wherein the believers read the Eddas or research papers on Proto-Indo-European cults, etc., and attempt to revive such worship in the present day. That they generally elide the central element of these cults — the sacrifice of animals and occasionally people — indicates that they are not, as a whole, quite as ready to dispense with normative liberalism as their druid robes might indicate. Others, reasoning that drowning men in fens to make the gods receptive to their entreaties might prove counterproductive (or at least unpopular) have embraced later and more intellectualized forms of paganism, being attracted to the ideas of the Neo-Platonists, Hellenistic mysteries, or, somewhat further afield, Hinduism. Others take a more comprehensive path, in keeping with ideas advanced by Traditionalists like Julius Evola, René Guénon, Mircea Eliade, and others. These theorists posited that there are primordial religious truths lost by an ever-more civilized humanity, but recoverable by differentiated individuals willing and able to explore beyond the bounds of convention. In brief, Evola believed that all existing religious traditions were too corrupted to operate within, while Guénon held that the esoteric truth was still present beneath exoteric forms. The latter converted to a Sufi sect in pursuit of this.

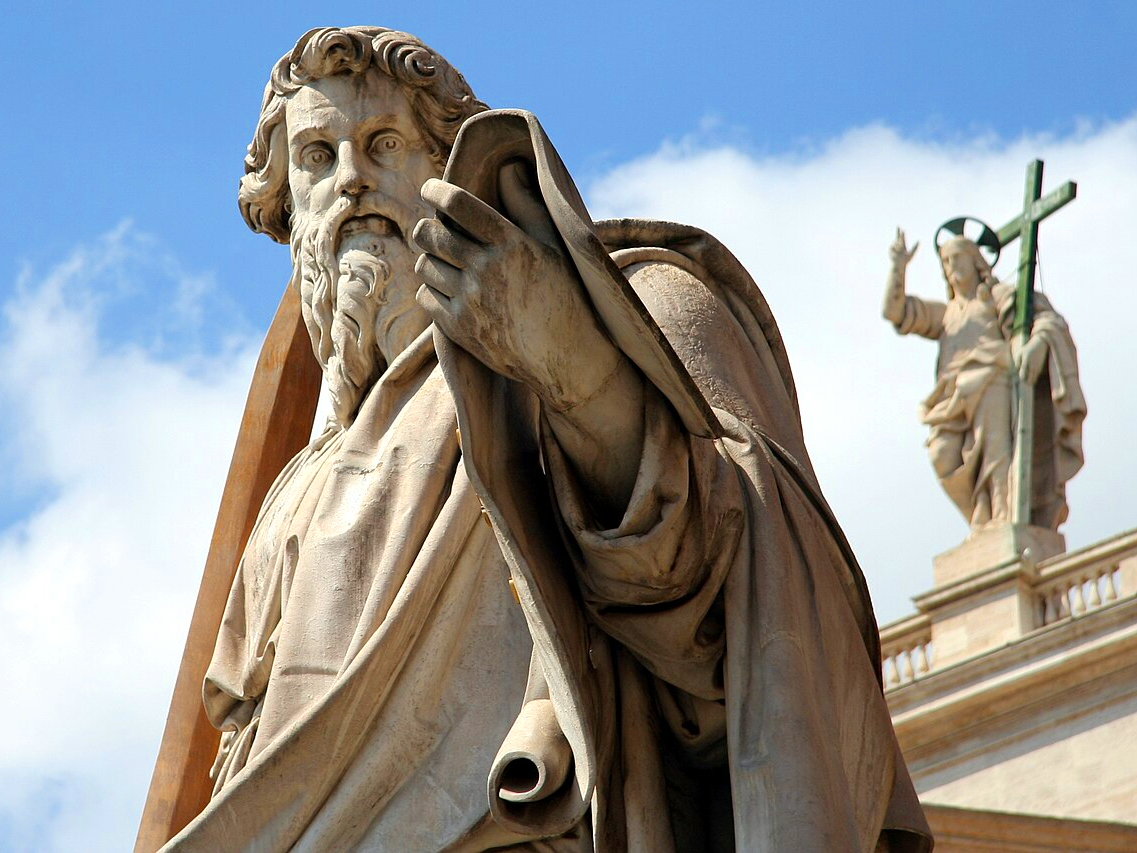

What is interesting is that while the Traditionalists generally rejected Christianity (Eliade was apparently Orthodox throughout his life, though he spent years studying Hinduism), Christianity anticipates and embraces something of their critique. The Apostle Paul, in the Book of Romans, is arguably the first theorist of the sort of decline noted by the much later Traditionalists.

1:20 For since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities — his eternal power and divine nature — have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that people are without excuse.

21 For although they knew God, they neither glorified him as God nor gave thanks to him, but their thinking became futile and their foolish hearts were darkened. 22 Although they claimed to be wise, they became fools 23 and exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images made to look like a mortal human being and birds and animals and reptiles.

Paul’s appeal here is to reason; the various nations of the Earth should have been able to deduce invisible realities from the visible evidence all around them. At one point they seemingly did have the sort of understanding he means, but then, due to pride, they fell away from it, and thereby into sin. But the possibility of arriving at some knowledge of God by way of reason is never ruled out. God, after all, never disappeared; men largely simply ceased looking for him save for those few moved to inquire into the higher things. Paul’s own experience as a Jew growing up in a major center of Hellenistic learning would have made him well acquainted with Greek philosophy. Tarsus was a major center of Stoic learning, among other schools, and Paul seems to have had as thorough a grounding in Greek culture as his own Jewish faith.

Paul’s missionary field was among those very gentiles among whom he’d spent his formative years. Speaking to the learned of Athens on the Areopagus, Paul gave this defense of his mission to the assembled pagans.

22 So Paul, standing in the midst of the Areopagus, said: ‘Men of Athens, I perceive that in every way you are very religious. 23 For as I passed along and observed the objects of your worship, I found also an altar with this inscription: “To the unknown god.” What therefore you worship as unknown, this I proclaim to you. 24 The God who made the world and everything in it, being Lord of heaven and earth, does not live in temples made by man, 25 nor is he served by human hands, as though he needed anything, since he himself gives to all mankind life and breath and everything. 26 And he made from one man every nation of mankind to live on all the face of the earth, having determined allotted periods and the boundaries of their dwelling place, 27 that they should seek God, and perhaps feel their way toward him and find him. Yet he is actually not far from each one of us, 28 for

“In him we live and move and have our being”;[d]

as even some of your own poets have said,

“For we are indeed his offspring.”[e]

29 Being then God’s offspring, we ought not to think that the divine being is like gold or silver or stone, an image formed by the art and imagination of man. 30 The times of ignorance God overlooked, but now he commands all people everywhere to repent, 31 because he has fixed a day on which he will judge the world in righteousness by a man whom he has appointed; and of this he has given assurance to all by raising him from the dead.’

He quotes Greek poets (Epimenides and Aratus) rather than Jewish scriptures and a careful reader will note that he calls here not for them to convert to his religion, but to return to their own. The idols that so repulsed Paul represented to him a rejection of something older and better, the primordial, authentic religion of the Greeks’ ancestors. The implication is that if they had the understanding of God that their forebears possessed, then Paul’s words would be manifestly true to them.

It should be noted that both the Christians and pagans of antiquity viewed an understanding of God rooted in pure reason or particular tradition as necessarily lacking. The most sophisticated and influential work related to this sort of knowledge of God in the ancient world was the Timaeus of Plato, which posited a serene and perfect Form of Good itself — the One (Τὸ Ἕν) — as the ordering principle of creation, a reality behind all realities. But this God as perfect idea, being perfect, must necessarily be indifferent to lesser beings, lest its perfection be compromised. Actual active creation was the province of a Demiurge, the exact nature of which is debatable, but in any case, these beings were not fit objects for worship; they could be pondered, but not reached. Later philosophers in the Platonic tradition would develop doctrines of super-rational ascension, but those post-dated Christianity. The Timaeus was influential in the translation of the Septuagint from Hebrew to Greek, less in terms of ideas than in the vocabulary that thereby entered the thought-world of Judaism. And it is here that the two worlds come together in the most profound way.

Both the Timaeus and Genesis posit a divine creator of all things, perfect and transcendent. But the God of the Israelites is also immanent, dwelling among His people. The God conceived of by Plato was pure being; the God of the burning bush who spoke to Moses declared in the Greek rendering of the scriptures “I am the Being ( Ἐγώ εἰμι ὁ ὤν).” Revelation was the missing element. This God, unlike the abstraction of Plato, made His presence known among men, and not just the initial desert tribe to whom He’d first made Himself known for His own reasons, but all men, by means of the atoning death of His Only Begotten Son.

Justin Martyr, himself a Hellene, called those Greek philosophers and spiritual teachers righteous who lived in accordance with the Logos. Clement of Alexandria created a school that taught worldly wisdom as a prelude to the Divine. Lactantius cited Vergil and the Sibyls as prophets of the gentiles who nonetheless understood something of the divine dispensation to come. They praised Zeno and Socrates as later Christians would praise the sober lives and wise doctrines of Confucius and Lao Tzu. Pace Nietzsche, the Church came not to invert the values of paganism, but to restore them to their original place, and to fulfill their promise.

The rightist instinct to RETVRN to older forms is a sound one, especially from the starting point of our degenerate age. But we must be thorough in our task. To arbitrarily grasp at the Age of Vikings or Homeric Heroes is to settle for a degraded part rather than the eternal whole. Yes, something of the religion of your ancestors is found in the Sagas and the Vedas. But the story will never be complete — and never right — without the final WORD.