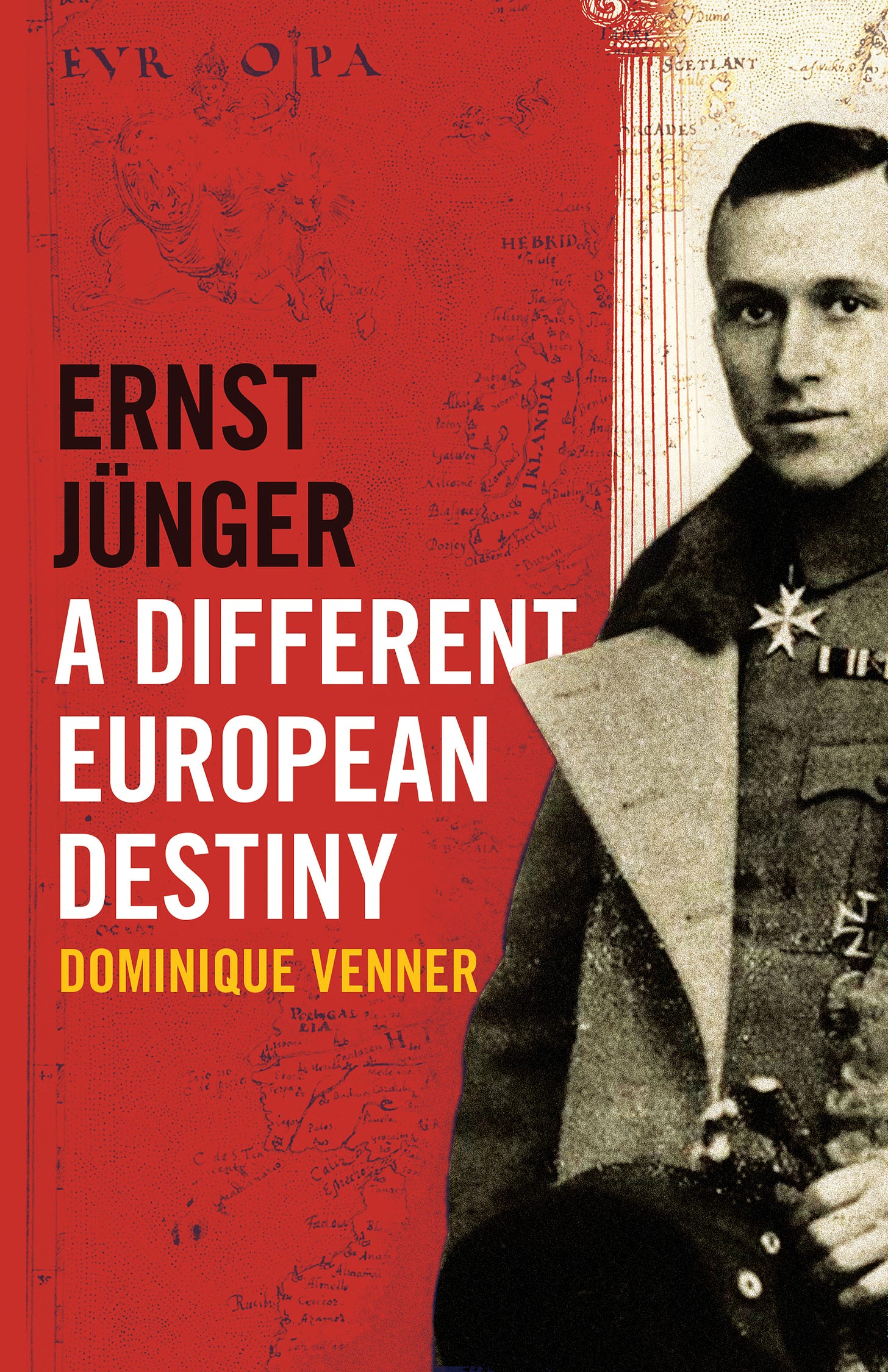

Ernst Jünger is celebrated in France yet scorned in Germany and Austria. But why is that so? In his 2008 book, recently translated into English by Arktos Publishing, French national revolutionary and historian Dominique Venner explains why the German war hero and conservative revolutionary Ernst Jünger is not only a monumental figure of the 20th century — serving as a seismograph of its immense upheavals — but also a guide towards a different European destiny.

Across 212 pages, Venner, who chose voluntary death in 2013 as a signal against Europe’s decline, not only provides insights into the numerous stages of Jünger’s life but also places them in their political and historical context. The Germanophile Frenchman focuses on the early works of the writer, who last resided in Wilflingen, which are particularly interesting for revolutionary nationalists. Venner traces Jünger’s journey, captivated by war, from his brief stint in the French Foreign Legion (African Games), his heroic service as a stormtrooper in World War One (Storm of Steel), to the rise of National Socialism and World War Two.

Venner highlights the vitalist worldview of the Nietzschean and revolutionary nationalist, who, as a staunch Prussian, preached the myth of service to the state and the total mobilization of all Germans through the military (The Worker), aiming to enable Germany’s renewal. For this, Jünger even sought an alliance with the Soviet Union to overthrow the bourgeois-liberal order. Jünger aspired to a national revolution and, in contrast to the scientifically social Darwinist myth of race, he embraced the Prussian myth of the state.

According to Venner, Jünger was aware of the German resistance’s activities but refused to participate. During World War Two, Jünger primarily served as an occupation officer in Paris, where he pursued translating his works into French and maintained connections with the Parisian intelligentsia alongside his military duties. The end of World War Two, marked by the death of his son Ernstel and Germany’s collapse, was a total catastrophe for Jünger, profoundly altering his life. Venner sees this transformation reflected in the figure of the Waldgänger (forest walker), which Jünger introduced in 1951 as a symbol of total resistance. This figure, akin to Martin Heidegger’s critique of technology, opposes the perilous development of a hyper-technologized world and advocates the individual’s total resistance against a criminalized society.

Venner concludes his portrayal of Jünger with the figure of the Anarch in Jünger’s novel Eumeswil. This character seeks only to rule over himself and, as a cold, indifferent observer of events, becomes the antithesis of globalists who seek to rule over everything.

Venner’s work is of interest to anyone wishing to explore Ernst Jünger’s writings from a patriotic perspective. Particularly striking is the national-revolutionary, martial, and pagan lens through which Jünger’s work is viewed, emphasizing its immanent-Dionysian thought. However, due to the book’s scope, the Christian-Apollonian aspects of Jünger’s later works are not addressed. For those wishing to understand Ernst Jünger, the Conservative Revolution, and above all his influence on France, this book is indispensable.

Buy Ernst Jünger: A Different European Destiny here.