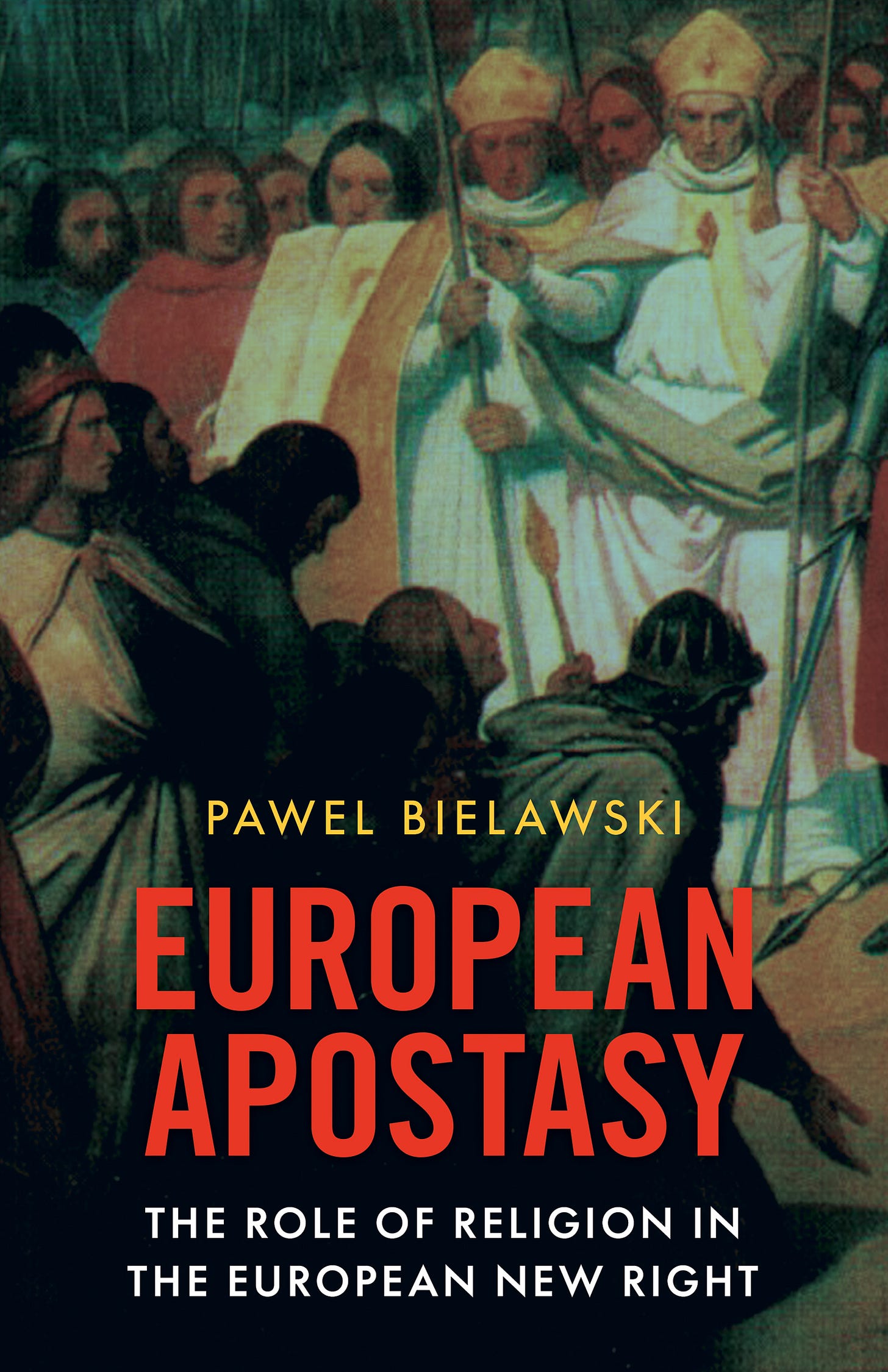

In European Apostasy, Pawel Bielawski delivers a meticulously researched, intellectually rigorous, and refreshingly honest study of the ideological foundations of the Nouvelle Droite (French New Right), with particular attention to the role of religion in the movement. This book is nothing short of a landmark contribution to the field of political theology and the intellectual history of European conservatism. It succeeds not only as a work of scholarly inquiry but as a profound meditation on identity, culture, and the spiritual trajectory of Europe in the modern age.

At the heart of Bielaawski’s study is an exhaustive examination of Alain de Benoist, the principal thinker and enduring voice of the Nouvelle Droite. The book functions as both an intellectual biography and a critical exegesis of de Benoist’s vast corpus, tracing the philosophical, theological, and political contours of his thought from his early years through the establishment of GRECE (Groupement de recherche et d’études pour la civilisation européenne) and beyond. Bielawski’s decision to focus primarily on de Benoist is both practical and justified, as no figure better encapsulates the complexities and contradictions of the movement.

What distinguishes European Apostasy is its layered, interdisciplinary approach. Drawing from political science, philosophy, religious studies, and history, Bielawski refuses simplistic or polemical treatments of his subject. This alone is a welcome departure from many previous English-language analyses of the Nouvelle Droite, which have tended to flatten the movement into caricature, often framing it as nothing more than an intellectual façade for fascist revivalism. Bielawski’s work, in contrast, approaches the material with methodological integrity and an openness that allows the ideas to speak in their own terms before subjecting them to critique.

The core thesis of the book is provocative and daring: that religion — specifically the rejection of Christianity and the revalorization of paganism — is not a marginal feature of the Nouvelle Droite, but its animating spiritual axis. Bielawski demonstrates how de Benoist views Christianity not only as alien to European identity but as the source of the egalitarianism and universalism that underpin both liberalism and socialism. In contrast, paganism is celebrated for its ethnic particularism, polytheism, and affirmation of immanence and difference. These religious dimensions are shown to be the metaphysical bedrock upon which the movement’s political and cultural critique is built.

One of the book’s many strengths is the clarity with which Bielawski maps out the ideological anatomy of the Nouvelle Droite across theological, philosophical, and political levels. His breakdown of these domains — while never reductive — makes the book accessible even to readers unfamiliar with the movement. The analysis of the Nouvelle Droite’s “political theology” is particularly illuminating, revealing how concepts such as desacralisation, secularisation, and the myth of progress are reinterpreted through a Nietzschean and Schmittian lens. In this reading, modernity is not a break from Christianity, but its secular continuation, a claim that flips Enlightenment historiography on its head and lends coherence to the Nouvelle Droite’s seemingly paradoxical critique of both religion and secular liberalism.

Equally noteworthy is the chapter on Islam, which treats the topic with a surprising nuance. Rather than resorting to the usual civilisational clash narrative, Bielawski examines the Nouvelle Droite’s ambivalent stance on Islam as both a threat and a potential ally in the critique of liberal modernity. It is precisely this kind of unflinching engagement with difficult and controversial topics that gives the book its intellectual gravitas.

The book’s methodological chapter is also a masterclass in academic self-awareness. Bielawski explicitly situates his work within the “political science of religion,” a relatively underutilised field that allows him to probe beneath surface-level political programs and into the realm of metaphysical commitments and value systems. His engagement with the work of Arthur Lovejoy, Quentin Skinner, and Hans-Georg Gadamer ensures that the study remains critically reflective throughout. By acknowledging the dangers of retrospective imposition and interpretative bias, Bielawski sets a high bar for academic integrity and offers a compelling case for how intellectual history should be done.

Though this is a work of scholarship, European Apostasy is never dry. Bielawski’s prose — thanks in part to Jafe Arnold’s lucid translation — is consistently clear, precise, and elegant. He brings to life the intellectual milieus of post-war France, from the militant energies of the Fédération des étudiants nationalistes (FEN) to the metapolitical ambitions of GRECE. His portrayal of Alain de Benoist’s intellectual development — particularly the influence of Nietzsche, Carl Schmitt, and the early New Right thinkers like Dominique Venner — is both sympathetic and critical, striking a balance that few scholars achieve when writing about ideologically charged subjects.

The comprehensive bibliography and extensive references make this book not only a study but a valuable research tool for future scholars. Of particular note is Bielawski’s engagement with Francophone and Polish scholarship, which is too often neglected in Anglophone academic discourse. By bringing these voices into dialogue with the broader literature on the European New Right, the book bridges intellectual divides and expands the conversation in meaningful ways.

Critics may object to Bielawski’s refusal to condemn or endorse the Nouvelle Droite outright. Yet this is precisely the book’s strength. In resisting the temptation to moralize, Bielawski models a form of scholarship that prioritizes understanding over judgment. This is not to say the book is neutral or without normative implications; rather, it invites the reader to confront the ideas on their own terms and to grapple with their internal coherence and external consequences.

European Apostasy is essential reading for anyone interested in the intersections of religion, politics, and European identity in the 20th and 21st centuries. It will appeal to scholars of political theology, students of European intellectual history, and even those in religious studies seeking to understand how metaphysical systems influence political ideologies. At a time when Europe is once again dealing with questions of cultural identity, religious heritage, and political sovereignty, Bielawski’s book offers a crucial perspective on one of the most significant and controversial movements shaping that debate.

In sum, European Apostasy is a tour de force of intellectual history — thorough, balanced, and deeply thought-provoking. It sets a new standard for the study of the European New Right and establishes Pawel Bielawski as a serious voice in the ongoing discourse on religion and politics in Europe. Whether one agrees with the Nouvelle Droite or not, this book makes one thing clear: the movement deserves to be studied with the seriousness its ideas demand — and Bielawski has done just that, and more.

Order European Apostasy here.