In the vast tapestry of time, few threads are as vibrant as that of June 6, 1944. That day, etched in the annals of history as D-Day, witnessed an armada of unmatched power, forged in the foundries of the United States and its allies, surging across the tumultuous waters of the English Channel towards the storm-lashed shores of Normandy. Yet, the tapestry, spun by the Fates, holds different shades of interpretation for different beholders. Viewed through the eyes of two distinguished right-wing thinkers, Jean Thiriart and Francis Parker Yockey, D-Day emerges as the threshold of an eclipse, a twilight of Europe’s independence and the awakening of an unchecked American dominion.

Thiriart, a vociferous advocate of pan-European unity, dreamt of a Europe that stretched her influence from Vladivostok to Dublin. Yet, his vision was ensnared in the creeping tentacles of American and Soviet ideologies, reaching into the heart of Europe. To him, D-Day signified more than a mere military operation; it was the spark that ignited the wildfire of American influence, a blaze that would eventually consume the entire continent.

Running parallel to this narrative was Yockey, a lawyer turned ideologue from America. In his magnum opus, Imperium: The Philosophy of History and Politics, Yockey dissected the decay of twentieth-century Western civilization. He too saw the American and Soviet impositions as the corrosive elements gnawing at Europe’s cultural backbone and political lifeblood. To Yockey, D-Day was not a victory for democracy but a harbinger of an American empire that threatened to topple Europe’s cultural identity and political sovereignty.

“The ‘liberties’ of the liberators”

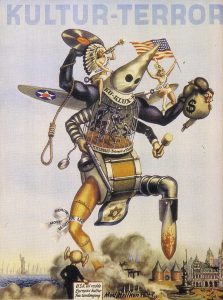

The currents that ebbed and flowed across Europe in the wake of D-Day were far-reaching and profound. As the Allies took their first tentative steps onto European soil, the toxic fumes of American influence did not retract with the cessation of gunfire. Rather, they transformed into a persistent cultural and political presence. The American way, an elixir of consumerism, liberal democracy, and individualism, was methodically distilled into the veins of a battered Europe. The traditional values, collective and ancestral, embedded in the bedrock of European societies, were gradually washed away by the tide of this new ethos, forever altering the landscape of the continent.

Europe, once the cradle of mighty empires, was demoted to a mere puppet on the world stage, waltzing to the tempo set by its American puppeteers. Its rich cultural legacy and identity were consumed by the ravenous maw of American pop culture, rendering Europe a dimmed reflection of its past grandeur. Europe’s intellectual fabric, interwoven with philosophical discourse and artistic innovation, was increasingly overshadowed by the metallic grind of American modernity. Thiriart and Yockey, witnessing this transformation, recognized D-Day as the bell tolling the beginning of an era where Europe was no longer the master of its destiny.

Thus, D-Day emerges akin to a mighty blade wielded by a warrior, gleaming with triumph on one side, casting a foreboding shadow on the other. The rising tide of American influence, much like a storm looming over a battlefield, was seen by Thiriart and Yockey as a threat to Europe’s sovereignty and cultural legacy. This presence, a direct consequence of D-Day, stripped Europe of its autonomy, much like Conan the Barbarian striding from primeval savagery into sophisticated decadence. The dawn of this day thus initiated the process of Americanization, irreversibly altering the socio-cultural landscape and steering the course of Europe’s history towards a future dominated by external influence.

History is not merely a record of triumphant cries and glorious victories. It also captures the subtle yet profound shifts in ideologies and cultural transformations. D-Day stands as not merely a military maneuver of colossal scale, but as an emblem of the dramatic shift in Europe’s cultural and geopolitical standing.

In the wake of the Normandy landings, the pillars of Europe – its governance and societal structures – were subtly yet systematically molded in the image of its liberator. The agents of American influence infiltrated every corner of European life – economics, politics, and culture. The Marshall Plan, while a salve for the ravages of war, also smoothed the path for the seeping of American-style capitalism across the continent. The ostensible success of this model, and its ideological seduction, accelerated Europe’s march towards Americanization.

Francis Parker Yockey stood as a lone sentinel, casting a discerning eye over the grand chessboard of global ideologies. Within the labyrinthine depths of his prose, he crystallized the ideological chasm that yawned between Europe and America – two landmasses bound by the chains of history, yet driven apart by the currents of ideology. Yockey, like a bard singing a ballad of clashing titans, presented a vivid portrayal of these opposing ideals, stirring the cauldron of thought and introspection with his powerful words. Cloaked in the mantle of a philosophical poet, Yockey penned a saga of confrontation between two giants, each reflecting disparate realities and values. Europe, with her ancient roots dug deep into the fertile soil of tradition, order, and socio-political stability, stood as the embodiment of hierarchy, duty, and responsibility. On the opposing end, America, the energetic offspring of the Enlightenment, was painted in the vibrant hues of equality, rights, and ceaseless flux, a monument to capitalism, materialism, and the rule of money.

The essence of Yockey’s ideological perspective can be distilled into this potent passage from Imperium:

Two ideas are opposed – not concepts or abstractions, but Ideas which were in the blood of men before they were formulated by the minds of men. The Resurgence of Authority stands opposed to the Rule of Money; Order to Social Chaos, Hierarchy to Equality, socio-economic-political Stability to constant Flux; glad assumption of Duties to whining for Rights; Socialism to Capitalism, ethically, economically, politically; the Rebirth of Religion to Materialism; Fertility to Sterility; the spirit of Heroism to the spirit of Trade; the principle of Responsibility to Parliamentarism; the idea of Polarity of Man and Woman to Feminism; the idea of the individual task to the ideal of ‘happiness’; Discipline to Propaganda-compulsion; the higher unities of family, society, State to social atomism; Marriage to the Communistic ideal of free love; economic self-sufficiency to senseless trade as an end in itself; the inner imperative to Rationalism.

Thiriart’s and Yockey’s critiques sprang from this painful witnessing of Europe’s unique identity and sovereignty fading away. They saw a Europe shaped not by its own historical roots and cultural essence but by an imported ideology, estranged from its soul. This disconnect, this sense of cultural dislocation, was a wound that traced its first cut to D-Day.

Both men, in their unique ways and in their days, yearned for a Europe that could assert its sovereignty, unfettered by the ideological chains of both the United States and the Soviet Union. They dreamt of a Europe that stood tall, projecting its values and ideals, instead of mirroring those of an external power. However, the specter of D-Day, and the resulting American occupation, cast a long, dark shadow over these aspirations.

Very good contribution indeed. Yet it is worthwhile to point out that American influence did not just begin with the landing in Normandy in 1944. As a matter of fact, American influence began about half a century before. It was much reinforced when the first American soldiers marched ashore in 1917. US movies and music (jazz and swing) were crucial in further increasing this influence, reaching far into the fibers of the European cultural tapestry.

Great article. Especially poignant was the fact that America’s entry into WW2 comes at a time when Western Europe was too bombed out and burned up to resist Washington’s rules and influence.

It’s also interesting that Jean Thiriart had a great influence on many men who survivor the inferno of WW2: Léon Degrelle – former Belgian SS officer and SS general – talks about Thiriart and agrees with the pan-European perspective.

The only thing uniting “America” is Germanophobia. Nothing else!