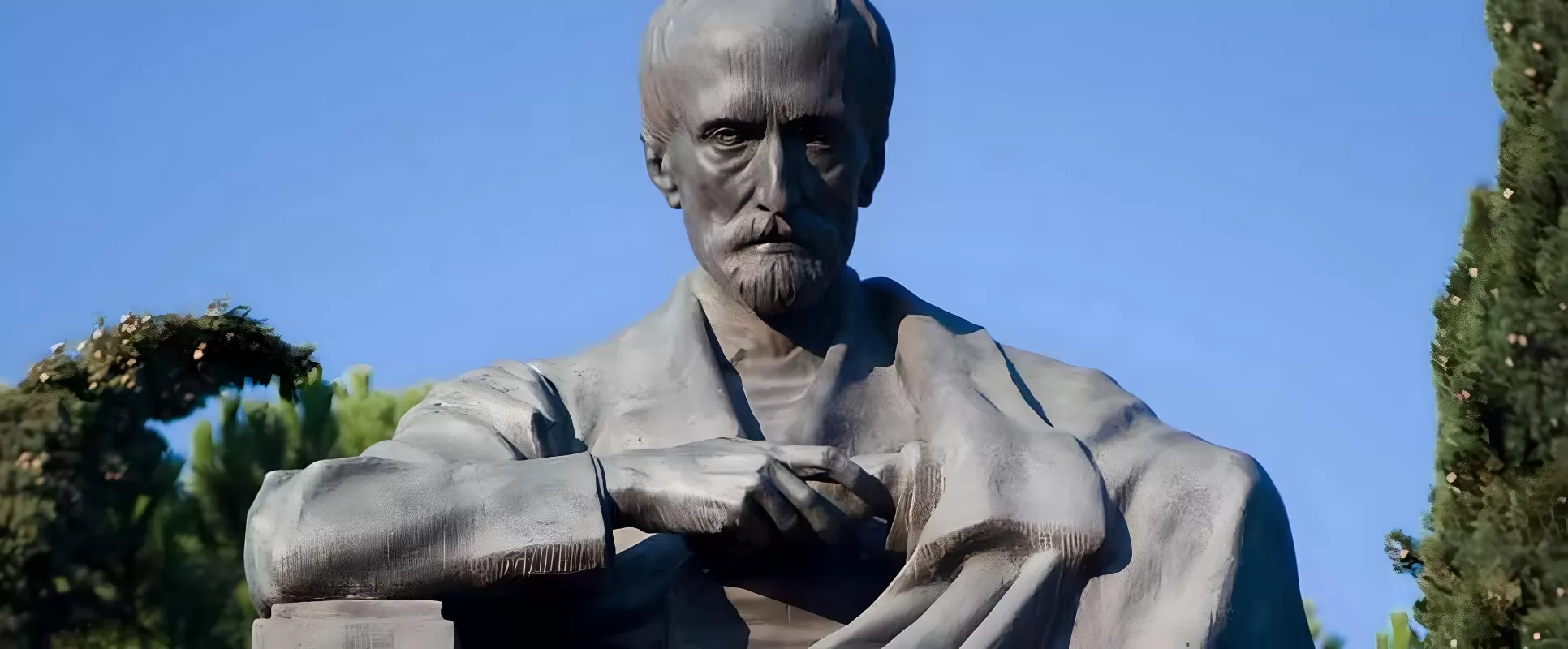

Let us continue our story for the readers of Arktos Journal about the political-philosophical views and political achievements of the Italian intellectual and political figure Giuseppe Mazzini (1805–1872).

During his stay in France, Mazzini founded the political organisation Young Italy (Giovine Italia), which can be considered the first modern Italian political party. Young Italy had its own newspaper, a propaganda machine, and crucially, the ability to convey its message to its target audience (the Italian middle class) and coordinate national liberation activities in Italy. It was then, in 1831, that Mazzini wrote his most famous early work – the ‘Manifesto of Young Italy’. The idealistic nature of the Manifesto is expressed by the author almost immediately: ‘Great revolutions are the work of principles, not bayonets.’ Mazzini asserts that to achieve a tangible, material victory, it first needs to be won in the minds and hearts of people, on a moral level. To attain freedom for nations, it is paramount to first propagate its principles. According to Mazzini, this is a lengthy process: as the human intellect is not capable of immediately grasping the principles of freedom, people need to be gradually introduced to these ideas through regular enlightening work. It is a task for many, united by one lofty goal.

Mazzini proclaims three principles essential for Italy’s development and prosperity: unity, freedom, and independence. In doing so, he contrasts the Young Italy movement both with those who are willing to sacrifice the country’s independence from foreign powers for the sake of uniting Italian lands under the singular will of a tyrant, and with those who, fearing violence, are not ready to fully unite Italian lands, settling instead for expanding the borders of one of the numerous Italian states. Mazzini opposes any compromises dictated by fear. The only authority he recognises in the Manifesto is the ‘will of the nation’.

Mazzini ponders how one can create a unified, free, and independent Italy. He counters those who, disbelieving in the very possibility of a popular uprising in defence of their own rights and freedoms and in the awakening of the people’s free self-awareness, advocate violent resistance using the same methods employed by tyrants to subjugate the nation. ‘They fail to comprehend that 26 million people, drawing strength in the pursuit of a noble cause and possessing an unyielding will, are invincible’, writes Mazzini. Are those advocating forceful methods truly prepared to die themselves for the liberation and unification of Italy? The author of the Manifesto doubts this. Those who call the people to the barricades usually stand aside themselves or, in other cases, things do not proceed to any tangible actions because the grandeur of the task intimidates even the potential organisers of the revolution. They do not believe in the people and wait for foreign aid. The ‘people of the future’, destined to create a united Italian state, must learn from the mistakes of the past. ‘They’, ‘people of the past’, with whom Mazzini debates in the Manifesto, are the Carbonari, a group of revolutionaries who formed an organisation of a Masonic type, aiming to fight for constitutional reforms.

Mazzini asserts that the past should have taught Italians that freedom never comes on the bayonets of foreigners. For him, a true revolution is a clash of principles and convictions, a war of the masses. Only committed idealists living by the idea they propagate can be the inspirers of a revolution. ‘Italy knows this; she understands that the secret of strength lies in faith, that genuine benevolence is sacrifice, and the right way is to prove one’s power’, writes Mazzini. The ideas and aspirations of Young Italy must be organised into a unified system; Young Italy should become a new element of national life, capable of creating a unified Italian state in the nineteenth century. In this process, Mazzini assigns a special role to literature, which must become the ‘moral clergy’, giving shape to true principles.

In a later work, Philosophy of Music (1836), Mazzini, in addition to literature, focused closely on Italian opera. Mazzini’s message was embraced by his contemporary composers, particularly Giuseppe Verdi, in whose operas Macbeth and Ernani one can discern motifs resonant with the nationalistic resurgence of the Risorgimento. Beyond Verdi’s works, who incidentally corresponded with Mazzini, one can highlight Gioachino Rossini’s operas The Italian Girl in Algiers, Moses in Egypt, and William Tell as compositions in which the calls of the Risorgimento are clearly audible – advocating national liberation, freedom, and resistance against foreign invaders and oppressors. (Gossett P. ‘Becoming a Citizen: The Chorus in “Risorgimento” Opera’, Cambridge Opera Journal, Vol. 2, No. 1 [March, 1990])

Reflecting on foreign policy, Mazzini believes that Italians should not focus on events in Europe, except in instances from which they can derive specific positive experiences and lessons in combatting humanity’s oppressors. Both pity and the assistance of other nations should be rejected by the Italians. According to Mazzini, Europe has yet to truly discover the nature of the Italian people. Ultimately, Italy will have to present to its foreign adversaries all the crimes committed against her. ‘We will tell the nations: these are the souls you bought and sold; this is the land you condemned to isolation and eternal servitude’, concludes Mazzini’s Manifesto.

The Manifesto, with all its revolutionary fervour and idealistic drive towards a new, freer, and fairer world, was timed with the foundation of the movement and the eponymous newspaper. Between 1831 and 1834, it published a series of writings that detailed the political stance of the early Mazzini. One of the most significant publications of this kind is the article ‘From the Collaborators of “Young Italy” to Their Compatriots’ (1832). In it, the Italian thinker elaborates on his views concerning the optimal form of political power, defending a republican position in contrast to both absolutist and constitutional monarchies, and championing principles of universal suffrage, social justice, and a rejection of privileges.

According to Mazzini, the key to the success of any revolution is the concentration of the maximum number of people’s efforts towards a unified goal. A revolution cannot succeed if it lacks a symbol, a purpose, and a vision of the future. Mazzini proclaims this symbol to be the republic. The Italian people possess a positive historical memory of the republic. Specifically, Mazzini references the experience of Renaissance city-states. The philosopher saw numerous advantages in the Italians’ history of republicanism; however, the long-standing existence of many independent states within the same territory, each with their own traditions and, in the later stages of the Risorgimento, views on their role in a unified Italy, posed significant challenges to the country’s unification process. It is necessary to convince the Italian people of the veracity of republican principles and, in line with the broader European trajectory of historical progress, make a historical leap through a single revolutionary uprising.

Thus, Mazzini champions the republic as the main objective. He disputes with proponents of a constitutional monarchy, viewing it as a ‘transitional form of governance’ from absolutism to freedom. His argument is that by recognising a monarch, power and the right to rule are granted, allowing them to decide on matters of war and peace and appoint governments. Moreover, the principle of inherited power remains, which is incompatible with the principles of equality and equal rights. Mazzini asserts that Young Italy should not count on alliances with any monarchs but instead should ‘raise the flag of the Italian people’, call it to battle, abolish all privileges, and make the principle of equality a religious symbol. Only in this way can monarchs and their aristocracy be defeated. ‘We are people of progress; we look to the future and aim for independence, regardless of our age, status, or the place where we live’, states Mazzini.

The method Mazzini promotes involves identifying the true principles and then, by spreading them, applying them to all significant areas: politics, economics, science, and more. Mazzini formulates the motto of the republican movement as: ‘Freedom in everything and for everyone. Equality in rights and duties, both social and political. Association of all nations, all free people, in a mission of progress that encompasses all of humanity.’ This formulation can be taken as a guiding principle for Mazzini.

It is interesting to see how Mazzini elaborates on the motto he proclaims. ‘The people form the foundation of the social pyramid… This is what unites all of us; it is the collective multitude that inspires us when we think and talk about the revolution and the rebirth of Italy’, writes Mazzini. By ‘the people’, he means the ‘total amount of human beings making up a nation’. The philosopher notes that a multitude of individuals does not constitute a nation unless they are governed by a single law for all, unified principles, and are bound by a common fraternal tie. ‘A nation is a word denoting unity: unity of principles, objectives, and rights’, Mazzini concludes. According to the philosopher, this type of societal relationship brings a multitude of people to homogeneous unity. Otherwise, what exists is not a nation, but a mob, an assembly of barbarians, temporarily united by the task of conquest, plunder, and robbery. A nation purposefully pursues shared goals of improvement and development in all forms of socially significant activity. The path to nation-building lies through the association of individuals. Mazzini introduces the antithesis of association: dissociation. The latter manifests when there is internal conflict between various social classes, as well as old and new orders. Mazzini cites examples of dissociation from the times of the fall of the Roman Empire: praetors against senators, plebeians against patricians, Christians against pagans, and philosophers against adherents of religious cults. Dissociation, according to Mazzini, is one of the conditions enabling a revolution.

Mazzini frequently revisits the issue of privileges: ‘When the equal distribution of rights is not a universal law, castes arise, along with privileges, domination, slavery, and dependence.’ Equality is essential for achieving social harmony, which is a condition of association. From Mazzini’s perspective, morally, all people are equal from birth. All individuals are equally predisposed to follow progressive tendencies if guided by true principles. There exists only intellectual inequality amongst people (this, according to Mazzini, is natural), from which a nation can derive advantage if utilised correctly. All other forms of inequality are a matter of law and can be addressed by society through legislation.

As a result of his contemplation, Mazzini comes to the following conclusion: ‘Equality, liberty, and association – only these three elements can forge a true nation.’ He defines a nation as ‘a multitude of citizens, speaking the same language and united under equal social and political rights, for the singular aim of growth and progressive improvement in all types of societal activity and societal forces.’ A nation is the sole legitimate sovereign; any power not emanating from the nation should be deemed usurped.

According to Mazzini, the will of the nation, as expressed by representatives elected for that very purpose, must be the law for all citizens. ‘One nation, one national representation’, Mazzini proclaims. This national representation should be elected not based on any form of census (whether property-based or any other) but on the will of all citizens. Every national representative should partake in elections. If an individual abstains from participating in elections, he does not have the right to call himself a citizen. Thus, according to Mazzini, the duty of national representatives is to enhance and manage societal forces to create conditions conducive to the common good. All societal institutions established must foster principles of social equality without jeopardising political equality. In Mazzini’s view, people’s representatives are obligated to become guardians of freedom, harmoniously balancing the quest for an individual’s freedom with the pursuit of the entire society’s progress.

Between 1831 and 1834, Young Italy operated underground, with Mazzini directing it from France. In 1833 and 1834, the revolutionaries attempted to incite popular uprisings in Savoy and Piedmont but were unsuccessful. After several years of wandering France and Switzerland, Mazzini settled in London in January, diving back into revolutionary activities with renewed vigour. He gradually garnered international fame, and his ideas gained traction amongst like-minded individuals from different countries. Young Italy evolved into Young Europe: organisations advocating Mazzini’s principles were established in Germany, Poland, Switzerland, and even Turkey.

Mazzini was even being discussed in the British parliament – the exposure of his correspondence by British authorities, which led to the disruption of a liberal uprising in Bologna, became public knowledge, making the Italian thinker a hero to English liberals. In 1848, Mazzini arrived in Milan, which had rebelled against Austrian dominance. Soon after, the Sardinian monarch, Charles Albert, launched a full-scale national liberation war against the Austrian Empire, facing a devastating defeat. Mazzini, joining forces with Giuseppe Garibaldi, fled to Switzerland.

At the same time, tensions escalated in Rome – the city’s inhabitants were outraged by the stance of the Pope of Rome, who backed the rule of the Austrian Habsburgs over Italian territories. In November 1848, open unrest began in Rome. The Pope fled the city, seeking refuge in the fortress of Gaeta, which was under the control of the Sicilian Bourbons. Garibaldi arrived in Rome…

On 9 February 1849, a republic was declared in Rome. Mazzini arrived in the city and was soon elected a member of the triumvirate, that is, one of the three alongside Carlo Armellini and Aurelio Saffi, rulers of the young state. The Republican government proclaimed the Pope of Rome was divested of temporal power, and the property of the Catholic Church was nationalised.

Mazzini tried to implement reforms he had long envisaged, but fate granted him only a few months – by July, the French army, called upon by Pope Pius IX, entered Rome, and Mazzini was again forced to flee to Switzerland.

The Roman triumvirate was the peak of Mazzini’s political career. Following unsuccessful uprisings in Mantua and Milan in 1852 and 1853, respectively, as well as the failure of a series of revolutionary demonstrations in Genoa, the thinker, once a central political figure of the Risorgimento and whom the formidable Austrian Chancellor Clemens von Metternich called ‘the most dangerous man in Europe’, merely became an observer of the forthcoming events of the much-desired unification of Italy…