MULTIPOLARITY! — this is the title of Constantin von Hoffmeister’s new book following Esoteric Trumpism. Although the term has also been used by the Identitarian Movement and similar groups, it is clear that this book revolves around Alexander Dugin and his political theory. Since Dugin’s early works were somewhat difficult to understand, it is helpful when others summarize and expand upon his theories. This is especially beneficial for newcomers.

Dugin also wrote one of the two forewords to the book. Interestingly, both forewords focus more on Donald Trump than one might expect. Dugin refers to his own article “Trumpo-Futurism,” which can be seen as one of several reconciliatory gestures towards Nick Land. This is surprising, as such references were not anticipated in the book. The second foreword also mentions other Großraum (large space)1 projects, such as China’s Tianxia concept,2 which adherents of the Fourth Political Theory should study more closely (and perhaps develop further with regard to countries like Singapore and South Korea).

It quickly becomes apparent that this book is far better structured and more focused on imparting knowledge than its predecessor.

The first main chapter of the book deals with ethnopluralism. Interestingly, von Hoffmeister primarily discusses Alain de Benoist’s softer version of the concept, highlighting that it can tolerate places like Düsseldorf’s Little Tokyo — now a famous tourist attraction for manga and anime fans. He then moves to Dugin’s further development of de Benoist’s idea. While de Benoist remains quite national in focus, Dugin applies the concept to international politics and large spaces.

Little Tokyo in Düsseldorf, Germany

Later in the book, von Hoffmeister addresses the harder-line demands for remigration and “foreigners out” (though Gigi D’Agostino is not mentioned) associated with Martin Sellner and his circle — but in less depth than his discussion of de Benoist. This emphasis aligns notably with Dugin’s focus on culture. (Martin Sellner, after all, shows little interest in culture — seeing a woke left-liberal as just as “authentically German” as a devout Bavarian farmer.) A key argument presented is that remigration is helpful and beneficial for multipolarity. This is logical: for example, Europe cannot be rebuilt as a Christian Western large space if a very large segment of its population now belongs to Islam due to migration policy. (On the other hand, remigration could ironically also assist other woke projects, such as gender ideology, by removing potential “enemies” of those movements. This presents a certain tightrope walk for conservatives.)

What is unfortunately missing is a weighing and reconciliation of the contradictions between de Benoist and Martin Sellner. To what extent are enclaves of non-European immigrants in Europe tolerable, under what conditions, and at what point should remigration be prioritized? Which non-Europeans are more tolerable in Europe — and which less so?

Remigration demonstration in Vienna, Austria

Unfortunately, such questions are not addressed. Instead, both concepts are presented and supported neutrally, leaving the reader to form his own opinion.

In Germany, there is unfortunately a group of Islam critics who see remigration as a way to save Western liberalism from Islam. (They also often wish to Westernize Islamic countries through war and other interventions.) Thankfully, Constantin von Hoffmeister is not one of these “neocons in a right-wing mask.” Instead, he acknowledges Islam’s significance and its legitimate living space. He simply does not want a mixture that would ultimately harm both cultures. This is a far more humane perspective than that espoused by many on the German Right — and one that deserves support.

The next chapter closely follows Dugin’s logic and outlines Halford Mackinder’s geopolitical theories. What stands out is that Constantin von Hoffmeister expresses far more disgust towards Mackinder than Dugin typically does, as Dugin usually treats Mackinder rather neutrally. But for a German author, this is not surprising since Mackinder’s geopolitical texts are also deeply racist pamphlets against Germans. The chapter touches on topics such as Ukraine and Iran. It concludes with a discussion of the internet as a geopolitical disruption and power shift. This point is especially interesting in connection with Dugin’s “Trumpo-Futurism” and the reference to Nick Land, who describes the internet as a disruptive force that shifts power away from the U.S. and towards China.

The next chapter is about Franz Boas, an anthropologist who criticized the idea of the West as the most developed culture and is therefore highly praised by the Left — but who is also extremely important to Dugin. There is a strong connection to the previous chapter as Mackinder did not count Germany and Russia as part of Western civilization but rather described them as barbaric threats to it.

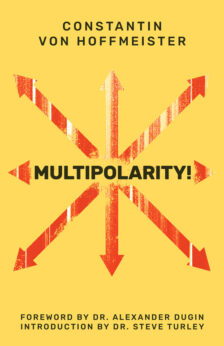

Almost directly following this, the next chapter is titled “Liberalism Is White Supremacism.” Although the title might initially sound “woke,” the chapter has nothing to do with Critical Race Theory or similar themes. It also does not dwell on ideas like “Whites secretly still hold all the power in the West,” which leftists often focus on. Instead, the chapter stays strictly in the realm of foreign policy. It begins with Rudyard Kipling’s poem “White Man’s Burden” and the thesis that “Western values” are essentially just the old racist colonial ideas dressed in liberal garb. And that is actually quite true. Liberal conservatives constantly rant about how “primitive” Islamic countries like Iran supposedly are and insist they should finally adopt “Western” influences. (While ignoring the fact that Khomeini’s advisors studied in Germany — i.e., they were already heavily influenced by the West.) Even in Western documentaries about otherwise “friendly” countries like Japan, one often hears a tone of condescension, where everything admirable about Japan is explained away as an attempt to imitate the West. (And in doing so, they ignore that Japan, especially among youth subcultures, produces a great deal of non-Western culture — and that Harajuku3 harbors more creativity than most Western metropolises.)

The White Man’s Burden

This racist attitude of “liberal Westerners” sometimes leads to truly bizarre assertions. For example, the Catholic German comedian Willibert Pauls once described communism as a “typically Asian concept of injustice inferior to the European intellectual tradition” — even though Karl Marx came from Trier, a German city.

In the next chapter, ancient Rome is highlighted as a positive contrast to today’s liberalism and the European imperialism of the 19th century. Ancient Rome, after all, demanded only loyalty to the emperor while generally leaving local cultures alone. Rome was also known for recognizing foreign gods as parallels or variants of its own deities, thereby granting other religions the same legitimacy as its own. The author then describes how the Soviet Union even encouraged ethnic consciousness in its provinces — something that later led to the fact that most non-Western leftists are just as nationally oriented as the Right (see, for example, North Korea or Cuba and figures like Ernesto Che Guevara). He also describes how Stalin distanced himself from Trotsky’s anti-traditional progressivism and once again supported religion and tradition (especially marriage). The author correctly observes that in Western Europe, the Americans destroyed much of traditional culture through their progressivism and consumer capitalism, which is why countries like Hungary, Poland, and the former East Germany are today far more conservative than the West.

This is followed by a chapter on Dugin’s “favorite philosopher,” Martin Heidegger. The author immediately corrects a common misunderstanding, especially among Sartre fans: Heidegger was far less liberal and individualistic than often portrayed in the West. He emphasized that one’s environment — including others and the surrounding world — exerts a profound influence on the individual. This also applies to Sartre himself, who often stressed how vital “being-with” is to human existence and how one can never fully escape the mental influence of others. All existentialists — including Kierkegaard and Nietzsche — are falsely portrayed in the West as radical individualists, and their collective dimension is denied. Some later existentialists like Simone de Beauvoir and Sartre are even misused to justify gender ideology. Interestingly, German feminist Alice Schwarzer, a former friend of Sartre and de Beauvoir, strongly opposes this appropriation and has written multiple times that neither de Beauvoir nor Sartre would have supported such “nonsense” as gender theory. Schwarzer, by the way, is now explicitly pro-Russian and has strongly criticized the West’s support for Ukraine.

The author rightly explains that Dugin brings the collective dimension of existentialism (that the “I” becomes itself only through the “You,” as existentialist Martin Buber put it) back into Western consciousness. The chapter also explains Heidegger’s critique of technology, especially his concept of the Gestell (enframing).

After this, the author turns to America, describing how the rise of multipolarity is leading to a loss of power for the U.S. and how the country is deeply nostalgic for its former dominance. One need only think of how many Westerners today worship the 1980s or 1990s as a lost golden age — and how many believe the machines in the first Matrix film were absolutely right when they said that the 1990s were the cultural peak of humanity. In this chapter, the author also discusses how America is being eroded by multiculturalism, immigration, industrial decline (the “Rust Belt”), and falling birth rates (a problem shared by Asia and Europe). He also notes how Western elites at times seem almost eager to “get rid” of their own people. Yet in the end, the author says that America could rebuild itself as a regional superpower — if it abandons the idea of global dominance. This chapter is likely the one most closely aligned with his Esoteric Trumpism.

In the following chapter, the author again criticizes White supremacist ideology and the Third Political Theory,4 and recommends Heidegger’s concept of Dasein as a better alternative to racialist ideas.

The next chapter is a critique of the Enlightenment and its anti-traditional tendencies (as seen in the Jacobins and their church desecrations), and a discussion of Guillaume Faye’s concept of Archeofuturism — a synthesis of futurism and Traditionalism — as a better alternative. A particularly striking argument is that the Middle Ages, with its belief in the immortal soul, valued the human being more. When one considers modern phenomena like biological experimentation, weapons of mass destruction, lobotomy, or the abusive use of psychopharmaceuticals to control people, there is something to this claim. Interestingly, the author advocates both a revival of Roman antiquity and a strengthening of Christian tradition.

He then turns to Africa and, with remarkable empathy, describes the problems and suffering caused there by colonialism. While many on the Right justify colonialism with arguments like “We could do it, so it was good,” or “We only civilized them,” or “But look how badly White people are treated there today,” the author shows real compassion and is willing to adopt positions uncharacteristic of the Right.

Instead of turning next to other cultural spheres — such as the Arab world, Confucianism, or the Indian tradition — the author shifts to Dugin’s daughter, Daria Dugina, and her philosophical positions on topics like racism and nihilism. On the one hand, this means that interesting questions — such as the future of North and South Korea (despite all sympathies for North Korea, South Korea is also interesting from a Traditionalist perspective, which creates a certain tension) — are left unaddressed. On the other hand, it is entirely understandable that the author would want to dedicate a chapter to her. I always found her very likable myself, and her death deeply affected me and even my otherwise quite apolitical girlfriend. Despite knowing almost nothing about Dugin or his daughter, she immediately urged me to write to him and offer condolences, solidarity, and help if needed. It comforted me later when Compact magazine in Germany allowed me to write an obituary for her. So I fully understand why Constantin von Hoffmeister would want to honor her memory and pay tribute to her.

Daria Dugina

After that, the author turns to Carl Schmitt’s thesis of the conflict between land and sea powers. As in Esoteric Trumpism, he argues that this distinction explains the ideological divide between Republicans and Democrats in the United States. Then comes a discussion of Hegel — though this time not about Trump “completing German Idealism” but about the concept of the Volksgeist (spirit of the people) and the rejection of Francis Fukuyama’s idea of the triumph of liberalism as “the end of history.”

This is followed by a chapter on Jean Raspail’s novel The Camp of the Saints, a book about a European refugee crisis that gained cult status among the German Right during the actual refugee crisis beginning in 2014 (alongside Michel Houellebecq’s Submission). Constantin von Hoffmeister, however, emphasizes a different aspect of the novel than its “prediction” of an immigration crisis. In the book, European elites are increasingly helpless in the face of the crisis — symbolizing the decay of Europe and its power. And this insight is absolutely correct. Take the Ukraine crisis, where Trump did more for peace on his own than all of Europe. Meanwhile, Europe ranted in a childishly immature way about how it was being perceived as irrelevant and even harmful by the rest of the world. Rather than admit failure and reconsider, European leaders preferred to escalate the war — even risking nuclear catastrophe. In doing so, the EU, once a “peace project,” made itself a global laughingstock. (As rightly pointed out by figures like Andrew Tate.) More generally, the European elite is embarrassing itself on the world stage. While the U.S. and China are making progress in AI research, Europe is introducing non-detachable bottle caps. It seems Nick Land was more right than we would like to admit when he said that the EU is merely a museum awaiting its well-deserved demise.

The author then returns to Guillaume Faye and argues that Faye’s Archeofuturism should be combined with Dugin’s theories in order to restore spiritual life force to Europe and lift it out of the “spiritual malaise” just described. Despite some problematic aspects of Faye’s vision (such as transhumanism), I find the idea of such a fusion quite good. Personally, I think one should also incorporate Mencius Moldbug’s neoreaction, as well as Nick Land’s theory of “templexity” (cities as time machines striving towards a state that is simultaneously past, tradition, and future).

In the following chapter, the author introduces Dugin’s concept of the “Archeomodern.” Archaeomodernism roughly means the survival of archaic thought patterns within modern systems. Dugin gave the example that many Russians saw the Soviets — and now see Putin — as a continuation of the Tsar, not as a new system.

Faye’s Archeofuturism is perfect marketing for today’s traditionalists and is well-suited to generating “hyperstitional” desires among ordinary people.

Towards the end, the book also touches on topics like the Iron Guard.

The book is very good and especially helpful for newcomers to the Fourth Political Theory. It is also commendable that the author tries to build bridges between Dugin and other European thinkers like Guillaume Faye — thus attempting to heal inner-Right conflicts such as the one between de Benoist and Faye.

The book is strongly shaped by the European New Right. Because of this, it does not fully meet Dugin’s claim of a “Fourth Political Theory beyond Left and Right.” There was potential to include left-wing critiques of technology, such as the Dialectic of Enlightenment5 (which, like Heidegger, sees Enlightenment as leading to inhuman technocracy). On the topic of multipolarity, one could have asked whether liberal concepts such as private law societies, Hans Hermann Hoppe’s theories, or Curtis Yarvin’s patchwork model could help realize it — and what the advantages or disadvantages of those approaches might be compared to New Right ideas.

Thus, the book remains more New Right than truly “beyond Left and Right.” A very positive aspect, however, is that it seeks to introduce European authors like Martin Sellner to a broader international audience.

The book is well-structured but often stays on a general level. It does not present any concrete proposals for political organization of a Eurasian large space. Nor does it engage with economic issues.

As already mentioned, the book also lacks a serious treatment of other regions such as Asia or the Arab world. Dugin’s view of postmodernity as both threat and opportunity is not explored. Nor is Julius Evola given much attention. (Unlike Dimitrios Kisoudis’s Goldgrund Eurasien, this book thankfully does not ignore Martin Heidegger in its discussion of Dugin.)

Compared to the author’s previous book, this one is far less emotional and more focused on the transmission of knowledge and ideas. Readers already familiar with Dugin’s work will find little new here. But as an introduction, the book is truly worth its weight in gold. People who want to explore Dugin’s work should probably start with Constantin von Hoffmeister’s book before attempting The Fourth Political Theory.

The essential concepts of Dugin and their history are explained very well.

(Translated from the German)

Order Constantin von Hoffmeister’s MULTIPOLARITY! here.

Footnotes

Translator’s note: Carl Schmitt’s Großraum theory proposes that the world should be organized into large geopolitical spaces (Großräume), each led by a dominant cultural-political power that excludes foreign interference. Instead of a universal liberal order, Schmitt envisioned a multipolar world where each large space reflects its own political values and civilizational identity.

Trans. note: China’ Tianxia concept envisions the world as a unified system with China at its center, where order and harmony are maintained through cultural influence rather than military domination. It sees all nations as part of a larger moral and civilizational hierarchy, guided by the central authority of a benevolent power rather than governed by equal, competing states.

Trans. note: Harajuku is a district in Tokyo that embodies Japan’s postmodern spirit — a vibrant stage where tradition transforms into futurism, and youth express ever-shifting identities in defiance of Western cultural conformity.

Trans. note: According to Alexander Dugin, the Third Political Theory refers historically to fascism/National Socialism as an alternative to liberalism (First Political Theory) and communism (Second Political Theory), but one that ultimately failed and must be transcended in favor of a Fourth Political Theory grounded in tradition, identity, and the sacred.

Trans. note: The book Dialectic of Enlightenment (1944), by Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno, argues that the Enlightenment’s pursuit of reason and liberation paradoxically led to new forms of domination through instrumental rationality, turning human beings into objects of control. It critiques modernity for reducing life to calculable systems, ultimately enabling totalitarianism, mass culture, and the dehumanizing effects of technological progress.