When nineteenth and twentieth century nationalism is discussed, a picture is often painted which has been cherry-picked and grossly distorted. Public schools and mainstream media across the now multicultural West teach us from childhood on that one nation emerged on the scene with a raging racial megalomania. We are told that a few key players possessed some sort of magnetic power, for they were somehow able to hypnotize millions of people and magically set them on some sort of crazed frenzy of maniacal madness. If we peer behind the curtain, however, we can see that pan-ethnicism was the true trend of the day. In fact, it is difficult to find any ethnic group in Europe that was not operating with the best interest of their own ethnic group in mind.

It should be shocking to anyone who has a cursory understanding of world history that this even bears affirming, but race and ethnicity are not figments of our imagination, they are biological realities. There is more to ethnicity than race alone. Language and other elements of culture separate one ethnic group from another. Indeed, modern genetics confirm what is clearly visible to any naked eye – that there are many ethnic groups found among Europeans. Phenotypic variation (facial features and other physical characteristics) varies by geographical origin on the European continent. The same is true for human beings on all continents. Historically, all humans were consciously aware of the uniqueness of their groups, that which made their group special and unique as compared to others.

With the overturning of the old traditional order during the Age of Enlightenment, revolutionaries began doing away with European royalty one royal family at a time. This, coupled with industrialization which made traditional livelihoods redundant and urbanization the new ‘normal’, it is no wonder that people looked around themselves to search for the familiar. The political Nationalist Era correlates with the cultural Romantic Movement which was a collective celebration of ethno-cultural roots. Amidst political upheaval, some ethnic groups sought to unify small independent states into larger nations for their own protection against larger neighbours. There is an unfortunate tendency to view the events that would unfold in the twentieth century out of context, ignoring the very recent unifications of Germany and Italy. But, it is still more of an injustice that other pan-ethnic movements of the same era are completely left out of the story altogether.

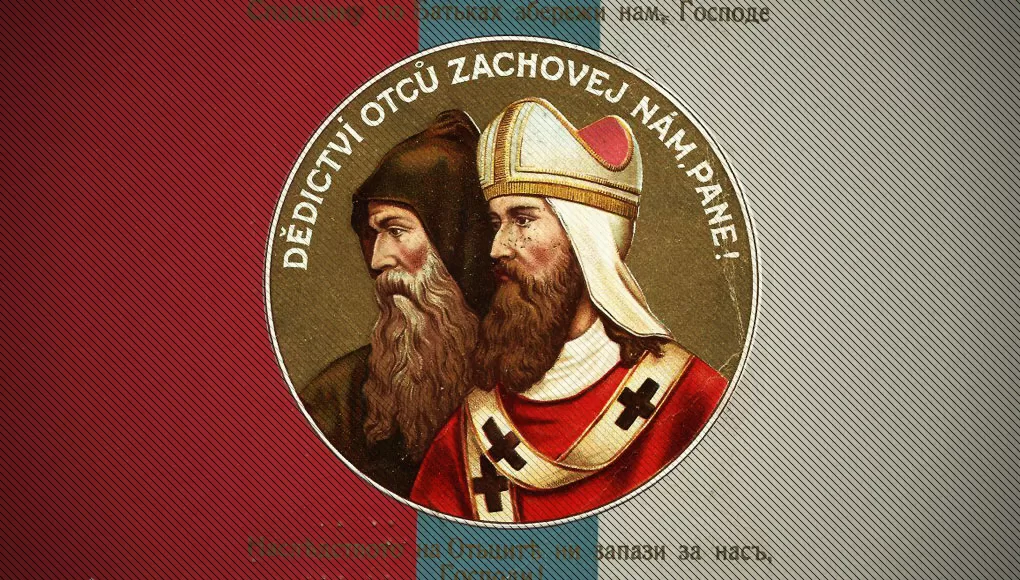

The Slavic situation, which in many ways parallels the German one, has been wholly overlooked in the Western interpretation of history. While pan-Germanism has been described as maniacal expansionism, there has been a corresponding failure to recognize that pan-Slavicism predated pan-Germanism. Indeed, in many ways pan-Germanism seems to have arisen as a direct response to the political and territorial aims of pan-Slavicism. Historians consider the 17th century priest, Juraj Križanić (born circa 1617 AD), as the first pan-Slavicist. He was a Croat by birth, but is most well-known for his desire to unite all the disparate Slavs into one entity under Russia. His own region in south-eastern Europe faced constant threat from ongoing invasions by the Turkish Muslims. To the West, Protestantism was catching on in German-speaking states. Križanić urged a unification between the Catholic and Orthodox Slavic factions to create one super-state in defence of competing regional factions. When a group of people find themselves under direct threat, it is natural for them to seek alliances with their kinsmen and to forge bonds based on shared ethnic heritage and cultural values in order to ensure their survival and longevity.

The pan-Slavic dream did not die with Jurag Križanić. Indeed, the song continued to be sung and the drumbeat only grew louder as time moved on. In 1848, almost one hundred years before World War II, Count Valerian Krasinski, a Polish aristocrat living in exile for having participated in a failed Polish uprising against Austria-Hungary, penned his book Panslavism and Germanism. Krasinski’s passion for his homeland and kinsfolk resonates through the pages. He says that, at the time of his writing, ‘the whole of Europe is agitated’ due to the political situation on the continent (p. 1). How familiar that sounds to us today. He goes on to speak of the dream of a Poland restored to self-autonomous rule.

One important element of Krasinksi’s tone is that despite the fact he writes in exile, his nation ruled by foreign forces, he speaks with a burning optimism that his dream will become a reality. He counters the notion that an independent Poland exists only in the realm of ‘Utopia’ (fantasy), and insists that the momentum for Polish independence is now more powerful than ever. His words are inspiring to ethnic Europeans facing attacks on our culture today whether or not we claim Polish heritage ourselves. He says (abridged):

We Poles, thank God, have never despaired of ultimately attaining that object, although we had no other means to rely upon than the sacredness of our cause and Divine Justice; for the sympathies of [other] nations, however strongly expressed had always proved nothing but empty sound. This faith remained unshaken under the most adverse circumstances. … It is true that all our efforts to emancipate our country, from a foreign yoke, had hitherto been unsuccessful. … They have proved however to the world that Poland was not dead; and that the Polish giant, prostrate under the oppression of the spoliating powers, who had vainly imagined to have assassinated him was, like Enceladus under Mount Etna, emitting flames and causing earthquakes. …

We do not entertain a doubt that Poland will soon be restored to a national existence, but it is impossible to foresee in what form and under what circumstances this now unavoidable event will be accomplished; whether it will resume its station amongst the independent countries of Europe, or become an important part of a great Slavonic state! Whether her future destiny shall be to form a barrier between Russia and the rest of Europe, or a vanguard of the united Slavonians against that same Europe! (P. 2–4)

It is interesting to compare the Polish Krasinski’s ideas a full two centuries after the Croatian Križanić’s. Both saw their nations nestled between larger intimidating factions whose actions on the geopolitical stage rendered their nations vulnerable. Both saw a unity of the Slavonic peoples as a vehicle for survival against competing ethnic groups. It is also interesting that two centuries later, Russia was seen as a potential friend or potential menace to other Slavs. Krasinski sees Polish survival as being possible under two scenarios: with Poland as a sovereign nation and a bulwark against Russia, or with Poland in a pan-Slavic union with Russia. How could Krasinksi have foreseen that a few decades later their neighbour to the West would see herself as the bulwark between Russia and the rest of Europe? More sobering, though, is the reality that Poland did indeed become one of many nations absorbed into a ‘great Slavonic state’, the United Soviet Socialist Republic, when the German bulwark against Bolshevism failed to hold the line against Marxist aggression. What Krasinski’s discussion does make clear, however, is just how complex the situation on the ground was in Central Europe at the time he was writing. Nothing arises out of a vacuum. Thus, the conditions described by Krasinski in 1848 are relevant to the events that would unfold in the following century.

It turns out that 1848 was a momentous year for pan-Slavicism, and Krasinski was not alone in his activism. The Slavic Congress was held in Prague that year, and it housed meetings for representatives in all regions of Slavonic-speaking Europe. For perspective, the unification of Germany occurred in 1871. The unification of Italy had begun earlier in the century, but was also completed in 1871. We can see that the post-war depiction of a Germany with a maniacal obsession with ethnicity is unfair when one looks at the concurrent ethno-national movements preceding and occurring concurrently with Germany’s own drive for unification of the German-speaking peoples. The desire for ethnic preservation and protection of ethnic Germans was equally felt among Slavs, Italians, Celts, and others throughout Europe. The International Celtic Congress held their first conference in 1901. And let’s not forget the World Jewish Congress, founded in 1936.

While modern Westerners are lulled into a feeling of complacency as we become minorities in our own homelands, anyone who takes the time to look carefully at how we got here can see plainly that the ethnic component in our own identities has been surgically removed. While they tell us that ethnicity is imaginary and protecting one’s own kind is racist, they blatantly lie about the unfolding of history. That natural drive to secure homelands and protect one’s own people asserted by Germany was, in fact, the Zeitgeist of the day for many European groups at that time.

Unfortunately, Slavic ethnic nationalism was co-opted by the Bolshevik movement. Interestingly, the Soviet movement is described as ‘antifascist’ in an article called ‘The Prospects of “Pan-Slavism”’ by George C. Guins, published in 1950. Antifa (Antifascist Action) was a political organization founded to promote Bolshevism in the West in the 1930s. Again, nothing arises out of a vacuum. Antifa is still active and making headlines today as they violently oppose any ethnic Europeans who dare to raise their head and speak out for national protectionism. What we are dealing with today is directly related to political happenings decades or even centuries ago, but we have been purposefully blinded to this.

Today, it is important for ethnic Europeans to recognize the plight that we all face and not let old rivalries cause bad blood between various European ethnic groups. However, we do have to look at those events in order to understand the events of the past. While we can consider former conflicts as the squabbling of sibling rivalry, we cannot look fairly at history and understand how it influences the present if we fail to look at it at all. Taking a critical position of nationalism, an American sociologist named Herbert Adolphus Miller said in his ‘Nationalism in Bohemia and Poland’, published in The North American Review in 1914:

No one can foretell the future political organization of Europe. Traditions, alliances, and antipathies will continue to exert an influence more or less in harmony with the past. There are, however, certain elemental states of mind whose development made the war upon which Europe has entered almost inevitable and which will continue to assert themselves until a political organization in harmony with their demands is accomplished. This war has been called a conflict of races – Pan-Germanism versus Pan-Slavism. The fundamental cause of the antagonism between these two peoples is neither racial nor economic; it is psychological. We call it Nationalism.

Nationalism is the struggle of a group to preserve its own individuality. It is even more elemental than religion itself, and, as in the case of the early Christian church, its growth to gigantic proportions has been fostered by the blind stupidity of rulers who could not see that the way to make it grow was to try to crush it. It is akin to patriotism, but draws its lines according to the group consciousness for a common language and traditions, or the feeling of unity of blood through some common ancestor. It does not correspond to national boundaries, but rather to historic or even imaginary boundaries. It is sentimental rather than rational. In fine, it is the revolt of a people conscious of its unity against control by influences trying to annihilate this consciousness. (P. 879)

Leave it to an American academic to simultaneously recognize that nationalism is ‘the struggle of a group to preserve its own individuality… against control by influences trying to annihilate this consciousness’, whilst condemning this desire as psychologically irrational. Removed from the action on the ground and separated from their own ethnic roots, most Americans simply could not wrap their heads around what Central Europeans were experiencing. Great Britain, an island with no immediate territorial threat to the borders of their nation, had only the economic standpoint to consider. Indeed, by 1959, barely a decade after World War II resulted in an Allied-supported Bolshevik victory, The Polish Review published an article asserting that ‘One of the most important of the nineteenth century intra-Slav gatherings, the one in Prague May 1948, has been overlooked and completely forgotten’ (Kimball and Zakrzewski, p. 91). Why has it been forgotten? Could it be that the same forces that hurl the words ‘white supremacy’ at anyone with white skin who dares to defend his ethno-culture are behind the transformation of Europe into the new U.S.S.R. and America into the racially ambiguous world capital of materialism?

At the time of this writing, the past few weeks have seen the so called ‘Yellow Vest Uprising’ spread from France to elsewhere in Europe. As I was writing this piece, I was sent a video discussing a small group of Canadians donning yellow vests and taking to the streets to protest the signing of the UN immigration pact. In both France and Canada, alternative media and private citizens are asserting that the yellow vest protests are directly related to mass immigration, while the mainstream media reports only their economic motivations. Yet, even among those who understand that unrestricted immigration has gone too far, most are afraid to stand up to it on ethnic grounds.

It is time to remember that we ethnic Europeans are a legitimate ethnic group with the same right to protect our homelands as any other ethnic group in the world. In fact, ethnic Europeans are sub-divided into many unique ethnicities – all of which are in danger of being lost forever if ethnic integrity is not maintained in our own sovereign nations. I urge every person who reads these lines to echo the words of Count Valerian Krasinski as he confidently asserted that the cause of his Polish brethren was sacred and that Divine Justice was on their side. His voice calls out from the pages and through time: ‘Poland is not dead!’

And I say to you that as long as there is breath in our bodies, the West lives! That American sociologist, Miller, was correct when he ascribed nationalist political rumblings to psychological factors, but not in the way he thought. There is a psychological war being waged to lobotomize ethnic Europeans and switch off our natural inclination to ‘preserve our own individuality against control by influences trying to annihilate this consciousness’. So we have no choice but to awaken the sleeping giant that resides in each and every one of us. We must speak. We must not be passive as our own kind are funnelled toward the horrors we see unfolding in South Africa today. The contrived genocide of our own people is in progress as we speak. And, only we have the power to stop it. But I echo Krasinski’s plea to his countrymen over a century ago when he urged his readers never to entertain any doubt that their nation would be restored to sovereignty. It took about a century and a half for his dream to come true, but today Poland is standing as a bulwark against the European Union’s Soviet-esque designs. Let all of us ethnic Europeans stand with her, shoulder to shoulder, and assert our divine right to protect and preserve our homelands.

Works Cited

Guins, George C. ‘The Prospects of “Pan-Slavism”’. The American Journal of Economics and Sociology 9.4 (1950): 439–444.

Krasinski, Valerian. Panslavism and Germanism (1848). London: Thomas Cautly Newby, 1848.

Miller, Herbert Adolphus. ‘Nationalism in Bohemia and Poland’. The North American Review 200.709 (1914): 879–886.

Petrovich, Michael B. ‘Juraj Krizanic: A Precursor of Pan-Slavism (CA. 1618–83)’. The American Slavic and East European Review 6.3/4 (1947): 75–92.

—. ‘The Slavic Idea of Juraj Križanić’. The American Slavic and East European Review 6.3/4 (1947): 75–92.

Zakrzewski, Stanley Buchholz Kimball and Jakub. ‘The Poles at the All-Slavic Conference of 1848’. The Polish Review 4.1/2 (1959): 91–106.

You continue with nationalism without being aware where the Germans come from or where the term Bohemia comes from, or Poland and what number state it is for whom? You should definitely read the chronicle of Dalimil if you want to know more.

Nationalism is also “grace” that can be extended only within a people. We all know, what we mean by a term, and even a joke. The opposite is the spectacle playing out in America’s Joke Congress between Ihlen Omar and American Jews, neither of which can discriminate between “Islamophobia” and “anti-Semitism” while America surrenders to the Taliban. In the more general pre-Darwin sense of the term, both terms refer to a race. Neither are American. They are immigrants. The disaster is that 3,000 Americans were mass murdered on 9-11 and we spent over a trillion dollars losing the longest war we ever fought simply because America is no longer a nation state and none of our leaders, including Donald Trump, really know what they are talking about when they talk about anything. A republic cannot be an imperial “world policeman”. Our Founders knew that and said so at a time when Americans did know what they were talking about. The Poles have their own sense of the world and I can understand how Pilsudski feared a Fourth Partition as well as Bismarck’s disparaging verdict on Poles. But, that’s just an understanding. It is not being a Pole. Pilsudski stopped the Eastern Reds in 1921. Poland, stop the Western Reds now!