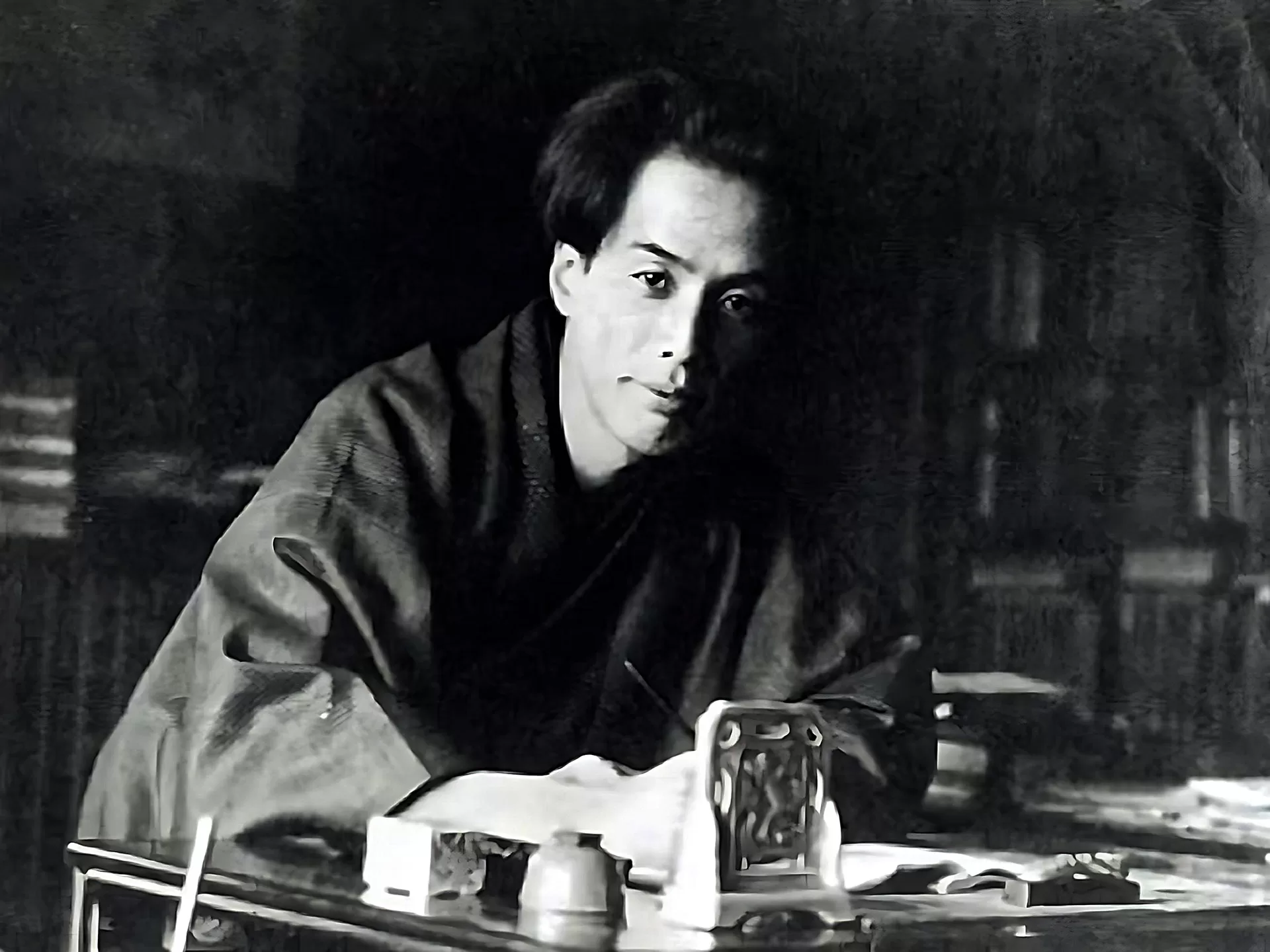

We live in a society in which language is no longer valued simply for its beauty or lyricism. In the modern era, especially in progressive Western society, language is valued mainly for its utility. Indeed, certain progressives espouse the notion that language has value only insofar as it is of use. This is a form of literary Puritanism. Even in the arts, there is little consideration for aesthetics. Beyond stripping words of their beauty and meaning, forcing them into the fields of utility, what is the favored use of these words by our modern progressive elites? To advance a thoroughly re-written narrative beginning with their own year zero. To erase history. To dilute the purity of culture and degrade tradition. Language itself has become weaponized for the sort of fetishistic utility that is lauded with a nearly religious fervor. In his philosophical treatise, Sun and Steel, the novelist Yukio Mishima wrote, “Words are a medium that reduces reality to abstraction for transmission to our reason, and in their power to corrode reality inevitably lurks the danger that the words will be corroded, too.” This corrosive propaganda has no use for beauty without meaning – for beautiful words to exist for their own sake.

There is great power that exists in meaningless beauty. From this beauty without the constraints of utility, poetry is born, and the artist is free to proclaim whichever truth or falsehood he likes, and an ugly truth or beautiful lie can come into being. It is only because words have become useful – that is, words have been transported from the realm of art into the arena of action – that they are presently considered violence by some. These people mistake their thin skin for sensitivity, perceiving slights and offenses at every corner. “Healthy” has been redefined as “sick until proven otherwise.” Indeed, they have infected society with their monomania. The society they champion decrees that words have the power to wound, and so they perceive themselves as wounded, and, as a result of their tantrums, the voices of the ancients are silenced. Because few of their opponents have the courage to stand up to this army of the deluded, and often even go so far as to indulge them, they shriek louder than ever.

When the voices of history can no longer resound, society does not necessarily choose new ones from what is beautiful or noble. When all social laws, such as class, hierarchy, and manners, are stripped from a society, that is, when the voices of the beautiful and the timeless have either been allowed to die out or else have been silenced, and when people are so preoccupied with the present that they forget the past and the future, when progressivism, obsession, and radicalism are roaming around like owls in the night, all of life is suppressed in its new hopes and activities. Material and social progress for its own sake has resulted in cultural stagnation. When the natural, improving will of human nature has fallen into such a state of mire and inactivity that it cannot be moved any further, people somehow continue to describe such a society as civilized. Academics make the “ironclad” observation that civilization is inherently progressive, characterizing the past as regressive, a cold appraisal of the so-called “civilization” of the general public, leaving little room for it.

The progressive upheavals in the literary and ideological world in recent years have made many of those involved in them extremely impatient. In a nasty way, it could be said that the word “modern,” which is often seen in association with the word “civilization,” means nothing more than “hasty and impatient.” From the same point of view, it is often easier and more accurate to interpret “we moderns” as “we hasty and impatient people.”

In such a situation, modern man is compelled to rebel against something to which he has been submissive. When he does rebel, however, he often forgets that this rebellion is the first step towards his own reflection – or, more practically, the improvement of his life. He rebels without understanding that which he has chosen to rebel against. With this, much modern art and literature aims at destroying for the sake of destruction, entirely forgetting that there is such a thing as destruction for the sake of creation, as done by such great artists as Caravaggio and Dalí. No, the progressive artist denies the validity of the classics, decrying them as “problematic” when viewed through the lens of modern sensibilities. Such an egotistical mindset is so absorbed in its own eternal present that there is no mindset in the world more hasty and impatient. This is not to say that such a mindset is entirely negative, for truly great art can be born from the deepest nihilism found in an eternal present. Osamu Dazai’s novel The Setting Sun comes to mind as an especially poignant example, written in the bombed-out ruins of postwar Tokyo. However, he did not style himself as a role model, nor did he paint an eternal present as desirable. “I am afraid because I can so clearly foresee my own life rotting away of itself, like a leaf that rots without falling, while I pursue my round of existence from day to day,” he wrote of such conditions. He broke with tradition in order to portray the sprawling hell of unconquered progress. But when an artist has such a mindset, he must realize that today’s art is the foundation of tomorrow’s art – that rebellion against conventional theories and customs is one way to create a new theory, a new custom. Civilization brings with it destruction. The problem lies in believing that this is the only form of creation.

Some may say that the above example is far from being “modern.” But let us consider a man whose work is, for example, writing poetry, who notices that his nervous system is more acute than that of conventional people, and he knows that this is one of the characteristics of modern man, and that he, along with these people, is in the unhealthy state which has been fostered by modern civilization. The same is true for the people of the past. Up to that point, fine. If, at that time, he quickly realizes that the qualification of a modern man is the keenness of the nerves, and he feels as if he is a successful candidate for an entrance examination who joyfully throws himself into the crowd of successful candidates – even though he is, in fact, a failure. But, he will be able to say to himself, “I am not a failure.” If they were to rely on their infirmity and pride themselves on it, and even more so, if they were to take various measures to promote their infirmity and press it to even further extremes, what would happen? We are presently seeing the results of such unfettered monomania. If, moreover, the so-called “new poetry” and “new literature” cannot be produced otherwise, then such poetry and such literature must be produced by those of us who, like myself at least, desire health and decent lives, and who seek to improve ourselves and our own lives as much as possible. It is no honor, in any sense of the word or for any man, to share the weaknesses of the times.

Hasty and impatient minds! I sometimes wonder if such a hasty mind is not one of the most striking characteristics of the modern American mind in particular. In the old days, man sought refuge in religion, and America, in particular, was founded on Puritanism, which has devolved into the neo-Puritanism that is progressivism. From the onset, the nation discarded the beautiful faith that had been practiced for centuries for their new form of zealotry. Today, it is a country that surpasses all other nations in the solidity and depth of its national organization. Therefore, if there is anyone there who truly harbors doubts about the relationship between the state and the individual, his doubts or defiance must be deeper, stronger, and more acute than those of any other country who harbor the same doubts. The progressive movement has been of such a nature that it must turn its spear against the established power of the state for the very same reason that it has tried to rebel against all old morality, old ideas, and old customs. But what have we heard from them? There, too, a cursing, compassionate haste has risen up in their minds, avoiding deep, strong, and painful consideration, and already they have a tendency to laugh at those who are serious about their faith and their art, in the same way as they laugh at wives who are considerate of their husbands, at husbands who are faithful to their wives, and at those who are not thin-skinned. More than any, they despise those who seek refuge in beauty. These hasty and impatient minds seek to elevate the mediocre as laudable.

“Those without a reason for existence are worthless,” the poet and translator Takashi Akutagawa wrote. A hasty mind is a mind without purpose. It is a mind that, in order to go from the top of this mountain to the top of the next mountain, has taken its feet off the ground in a single bound, without taking the path that it should naturally take. This is the most dangerous thing of all. A mind that has lost its purpose will bankrupt the meaning of a man’s life. If a man is to consider the problems of life, he must despise the practical problems that make up the content of his own life, and through sheer momentum, he must then come to despise the self, itself. It is already a contradiction, ridiculous and tragic, that a man who despises himself should think about life. What can we learn from such people? What beauty is to be gained from such an existence? What edification can come from their creation? This is why some, such as I, criticize their writing as cheap confession and imaginary skepticism.

When these “artists,” who lack the knowledge that is the basis of all their actions and the policy of all their speculations, try to discuss even the slightest matter, they are met with errors of observation, contradictions in reasoning, and a myriad superimposed contradictions. One is that they see the temporary state as a permanent tendency, and the other is that they consider the local aspect as the essence of the whole. If such a hasty mind, with its contempt for the self, its pride in sharing the weaknesses of the times, were “modern,” or if so-called “moderns” had such a mind, we should rather retreat and rely on the fact that we are more “non-modern” than they are. We should be proud of it. Then, with the least haste and impatience, we should follow through on our efforts to improve our own lives as quickly as possible, to unify them and to make them more beautiful.

I am not here to discuss the meaning and qualities of civilization, but if we call the above state of affairs a true civilization, then the “civilization” that is the pride of modern man is not a civilization at all. Everyone desires freedom. Obedience and self-control are human virtues, but the desire for this freedom to govern one’s own life is rarely too strong among the masses. Those who even remotely agree with Carlyle’s observation that history is only the biographies of great men cannot possibly deny the great authority of this desire and its majestic triumph. The desire for freedom is not merely the desire to free the individual will from political or economic bondage, but the desire to create, develop, and govern his own future by his own strength. It is the desire to be one’s own sovereign and to use the whole of one’s faculties for oneself. The most intense of these desires is the genius. Genius is, after all, nothing other than the power of creativity. The history of the world is, in short, the story of the ever-changing evolution of this fierce personal desire for independent creation. If you think that is a lie, just try to erase all the heroes of genius from the history of the world. All that remains is an ugly, ordinary corpse, which is beyond even my imagination.

The desire for freedom, however, is always hated like a scorpion and feared like the devil in a progressive society that has already formed an onerous law of death. Those who wish to create their own heaven and earth against a society that binds the rights of the individual with the ersatz laws adopted by various progressive factions must first of all adopt an attitude of defense and take aggressive action. When the encirclements are finally restrained, they will rebel against them and destroy them. Those progressives who force their increasingly demanding restrictions on the public, as well as those who disagree with such restrictions but nonetheless allow themselves to be bound by the ropes of so-called respectability, who devour sleep in the narrow prison cells which they have allowed to be built, will here persecute our brave invaders with all their might, with all their strength, with all their blood, and with all their hearts. Thus, life is a perpetual battlefield. Society battles the individual, the young battle the old, progress battles conservatism, and cowards battle those who refuse to be silenced by them. Those who win are transformed into stars in the heavens of history, and the radiance of their genius shines through the ages. Those who are defeated and covered with earth will remain in unceasing bitterness, making those who feel compassion for them weep for eons. Those who win are few, but those who lose are many.