Dehumanizing the enemy, as harsh as the term may sound, has been one of the most common practices throughout human history. Dehumanizing does not only mean assigning inferior characteristics to an adversary (i.e., dehumanizing through sub-humanizing), but also includes attributing such despicable and reprehensible characteristics to the other that their elimination becomes legitimate and, in many cases, legal.

The recent Russian incursion into Ukraine under the pretext of de-Nazifying the territory is an example of this dehumanization, since no modern, liberal man wants to be a Nazi or have Nazis around, so cleaning up a space of Nazis is perfectly legitimate after the end of World War 2. Paradoxically, the pro-NATO side accused the Russian government of having practices similar to Nazism. Dehumanization versus dehumanization.

Civilization progresses in a similar way to the legitimacy that arises to combat dehumanization, but this is not arbitrary. Instead, it rather follows archetypal visions rooted in the deepest of human nature.

As humans moved away from hunter-gatherer and pastoral-horticultural economies and into the need for settlement, religious thought also underwent adaptations in the myths that fertilize and justify not only the evolution of ways of life but also the projects that men undertake. With the change in economy, cultures also mutated in the religious and mythological realms. Thus, the spiritualities that were once associated with the earth, the maternal, the horizontal, the sparsely mutable (lunar cycles succeeding incessantly for tens of millennia), the elemental beings, the primordial and the uncontrollable, came to be associated with the sky, the high, the patriarchal and hierarchical. As the earthly was progressively desacralized and the spiritual relegated to the firmament, it became necessary to resacralize the earth.

In the sky, humans found inspiration, an example to replicate on the surface of the earth. Celestial prototypes transformed into extraterrestrial archetypes (that is, outside of Earth) would henceforth direct human endeavors. Through the tale in which certain celestial deities implement order on the formless mass, acts of ordering pre-existing chaos, of the shapeless and undifferentiated, that is, the cosmicization of chaos, are translated as acts of Creation. In this way, pastoral settlements increased in complexity to transform into cities, taking space away from the chaos of the uncultivated, the unknown, and disordered, which also included those “savage” cultures lacking virtue that inhabited those territories.

With the celestial archetype of the Center as a guide, the city took on a preponderant role in culture, extrapolating its creative power beyond the borders of the known. The imperialism that arises from the city is different from the imperialism that arises solely from tribalism: while the former justifies its destructive power in Creation – the establishment of civilization – the latter practically has no further justification to do so because power grants the right. Rome was responsible for leaving the most enduring mark possible in each conquered space, that is, civilized, within the five million square kilometers of its empire, whether it be language, constructions, or legal systems – imposing its culture. On the other hand, the Mongol empire, by devastating every village, town, and city in its path, conquered about 24 million square kilometers that extended from the Far East to Eastern Europe. Unlike the Roman case, Mongol horsemen ended up assimilating to conquered cultures, acculturating themselves.

Each advance of civilization is an act of Creation. This is not, in some way, a kind of legitimization of the atrocities and destruction that imperialism, in its civilizing mission, incurs, but it serves, nevertheless, to understand the underlying desire of the advance of civilization: each bomb dropped, each government overthrown, each military incursion, each culture subjected to hegemony, each installation of a puppet government, arises as an act of Creation, because where there was once chaos and barbarism (that is, any form of culture that did not reflect the values of celestial archetypes – the civitas), there is now an extension of the city: the Cosmos.

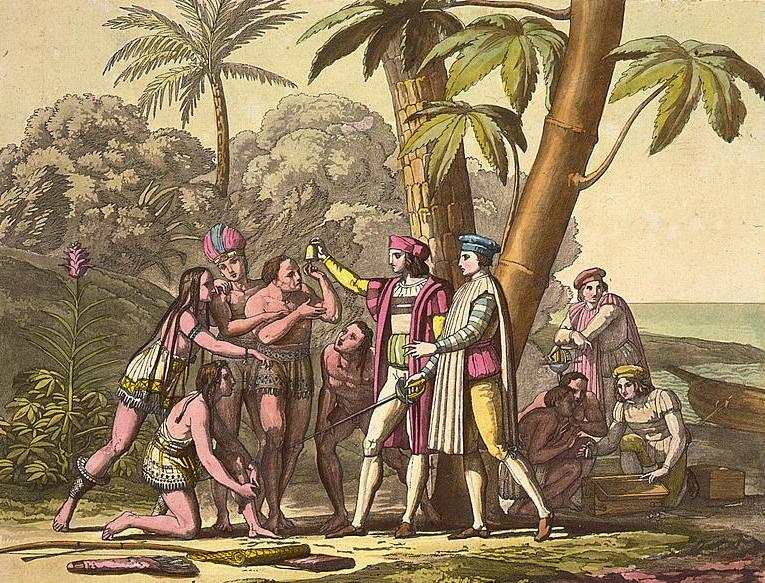

With the Cross as a symbol of the celestial virtue that sought to be reflected on Earth and of the Cosmocrator, European navigators led by Christopher Columbus took possession of the New World. This consecration of an unknown land – as an archetypal repetition – gave it a new birth, a baptism, to what was visible before the Old World. Unlike the other enterprises of European navigators of uncivilized cultures who ventured through America several centuries before Columbus, the Conquistadors were guided by the expansion of civilization. To the “savage” (that which is terrestrial but is outside of civilization) would come the Order that would show the way to civilization, first manifested as Christianity and then as Democracy and Human Rights.

For civilization, the mere existence of chaos and barbarism is sufficient justification for the advance of its cosmicization, those efforts invested in putting order where there is the desolation proper to the lack of civilization (e.g., Libya, Tunisia, Iraq, Egypt or Yemen). And dehumanization can always be employed for cosmicization; but whether this future cosmicization will be American, Russian, or Chinese remains to be seen.

Very well written. Indeed, the concept of “civilisation” tends to have an intrinsic expansionist drive in it, one based most often in material needs and desires but usually cloaked in a veneer of “humanitarian” goals

The National Socialists of Germany and the Imperialists of Japan, may, indeed, have sincerely believed that they were bringing Civilization to their enemies. The National Socialists, in particular, took Civilization to its logical conclusion– ad absurdum. And, the National Socialists, of course, have been resented ever since!