The stage of existence, vast and foreboding, witnessed the birth of a titan – a man destined to duel with the monstrous apparition of Being itself. He was christened Robert E. Howard. A son of the untamed Texas frontier, he greeted the world on the frost-anointed morning of January 22, 1906. Fostered by a mother whose intellect was as potent as a wizard’s elixir, Howard embarked on a journey into the wild frontiers of imagination – a journey that would leave indelible marks upon the annals of fantasy literature and true American culture.

His tales, tempestuous as the primordial oceans, were deeply rooted in the soil of existential inquiry. Like a seasoned adventurer, Howard plunged into the cavernous abyss of existential dread, wrestling with its monstrous denizens. From this epic conflict, he forged tales that mirrored the profound philosophical musings of Martin Heidegger, the intrepid explorer of Being. Howard’s sagas, etched in the timeless stone of human contemplation, resonated powerfully with Heidegger’s dissections of existence and mortality.

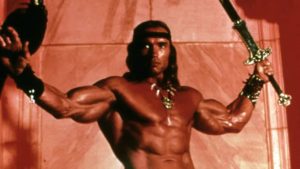

Among the legion of Robert E. Howard’s imaginative prodigies, the figure of Conan the Barbarian dominates the stage like a towering colossus of old – his broad shoulders casting a shadow that stretch far into the horizon of literary history. With his indomitable spirit and relentless vigor, Conan is the embodiment of Heidegger’s profound philosophical concept of “being-in-the-world.”

To comprehend the depth of this Heideggerian concept, one must embark upon a voyage into the stormy seas of existential philosophy. The notion of “being-in-the-world” suggests that our existence is not merely an isolated entity, confined within the skeletal walls of our physical form. Instead, it is intrinsically linked to our interactions and engagements with the world around us. It acknowledges that our individual being is inextricably entwined with the world in which we exist.

Heidegger’s philosophy rejects the Cartesian idea of a separation between the subject and the world. Instead, it proposes a sort of co-being with the world. Conan, too, lives as part of his world, not as a separate observer but as a participant, clashing with the barbaric chaos of his realm. He thrives amidst the turmoil and strife, asserting his existence in a world indifferent to his mortality.

This ties into another aspect of Heidegger’s philosophy, the concept of “being-towards-death.” Heidegger held that an awareness of death gives life a sense of urgency and authenticity, a driving force behind our existential striving. Conan, with the shadows of death ever-looming, danced constantly on the precipice of mortality. Yet, instead of shying away from the always-present grimace of death, he met it head-on with a defiant roar. Conan’s life was a perpetual storm battering against the cliffs of mortality – an embodiment of Heidegger’s “being-towards-death.”

In the primal landscape of the Hyborian Age, Conan’s words rang out with raw existential truth: “I live, I burn with life, I love, I slay, and am content.” This crude but potent declaration was a clarion call of Heidegger’s concept of “being-there.” Conan did not merely exist – he was intensely alive, unabashedly asserting his presence and significance in the indifferent void of the cosmos. His declaration personified the heart of Heidegger’s “being-there” – the ceaseless affirmation of one’s own existence, one’s own “being-there” amidst the whirlwind of the world.

So it was that Conan the Barbarian, with his wild and tempestuous life, encapsulated the Heideggerian concepts of “being-in-the-world,” “being-towards-death,” and “being-there.” The fierce Cimmerian did not just live – he wrestled with existence itself, gripping it in a bear hug of defiant affirmation. His life was a dance on the edge of the existential abyss, a dance that mirrored the philosophical explorations of Martin Heidegger – a testament to the undying spirit of mankind in the face of the eternal void.

However, the philosophical jewels within Howard’s tales spanned far beyond the rugged, high-born realm of the bronze-skinned Cimmerian. From the somber wanderer Solomon Kane, a man driven by a relentless pursuit of justice and ensnared by the unforgiving jaws of existence, to the brooding Kull of Atlantis, a king wrestling with the ethereal nature of power and the shifting sands of civilization, Howard’s characters sailed along the existential maelstrom embodied in Heidegger’s philosophy.

Solomon Kane, the relentless wanderer cloaked in Puritan resolve, was more than a stalwart champion with sword and flintlock at his command. He was a man ensnared in the tumultuous seas of his own being, impelled by an unyielding urge to seek justice, a grim specter striding forth against the blood-tinged backdrop of disorder and lawlessness. His terse utterance, “Men shall die for this,” from the tale “Red Shadows,” was not the mere vow of an avenger. It resonated with a deeper meaning, reverberating within the existential chasms of his existence, and hinting at Heidegger’s notion of “thrownness.”

In Heidegger’s existential framework, “thrownness” encapsulates our unexpected entrance into a world not of our choosing, a world fraught with pre-existing societal scaffolds, cultural codes, and prevailing values that shape and mold our lives before we even grasp the reins of our own destiny. This concept encapsulates our fundamental lack of dominion over our roots and the circumstances of our birth. Kane, shrouded in his unwavering ethos of morality and justice, seemed to embody this Heideggerian concept. He found himself hurled into a world teetering on the border of malevolence, and he devoted his very essence to pulling it back from the brink. Such is the path of Solomon Kane, reflecting a man thrown into the existential battlefield, his soul alight with the flame of duty.

The philosophical breadth of Howard’s tales, however, did not end at the gloomy trails of Solomon Kane. It extended across the stormy seas, beyond the veil of time, to the melancholic throne of Kull of Atlantis. Kull was not a king insulated by the ornate trappings of power; he was a king haunted by its ethereal nature and the fleeting illusion of civilization.

In “By This Axe, I Rule!,” Kull ponders his existential predicament, noting, “Rush in and die, dogs – I was a man before I was a king.” His words betray an acute awareness of the transient and illusory nature of power, an awareness that deals with the profound emptiness lurking beneath the glittering surface of his kingship. This introspection resonates with Heidegger’s critique of inauthentic existence, where societal norms, expectations, and roles often lead us away from our authentic selves, burying our personal aspirations and desires beneath the weight of collective structures.

Thus, whether through the death-haunted wanderings of Solomon Kane or the introspective broodings of Kull, Howard’s characters are far more than mere heroes of pulp fiction. They are the embodiments of Heidegger’s existential philosophy, their struggles a sign of mankind’s ceaseless quest for authenticity and meaning amidst the stormy seas of existence. Their stories remain, their battles etched in the annals of literary history, ever reminding us of our own “thrownness” into the world and our perpetual exertions against the existential tide.

Howard’s life, like a comet streaking across the cosmic stage, was a poignant mixture of brilliance and brevity. His self-inflicted shotgun death at the age of thirty marked the final scene in his personal narrative of “being-towards-death” – a philosophical reality he explored with a raw intensity in his tales. As Heidegger famously mused in his seminal work Being and Time, “As soon as man comes to life, he is at once old enough to die.” Howard’s life and tragic end, thus, embodied this disquieting concept, leaving behind a legacy resounding with echoes of existential contemplation.

In the ceaseless campaign against their impending mortality, the heroes forged in the crucible of Howard’s imagination blaze with a soaring spirit, standing as mighty torchbearers in the face of existential darkness. Each character, shouldering the colossal weight of his existential plight, fought his battles with the raw valor and primordial resolve of an ancient demigod, channeling the unadulterated essence of mankind itself.

Just as Heidegger’s philosophical ideas were forged in the dense, shadowy quietude of Germany’s Black Forest, the rugged wilderness of Howard’s native Texas served as an equally profound backdrop to his own existential journey. Both landscapes, fraught with their unique trials and tribulations, were arenas for the grand theater of existence. Heidegger, with his Black Forest pathways disappearing into the mist, and Howard, with his sun-scorched Texan plains stretching beyond the horizon, found themselves at the mercy of their landscapes’ unforgiving and stoic beauty.

In a ghostly farewell, Howard conveyed a sentiment soaked in fatalistic resignation. His words, haunted by sorrow and exhaustion, unveiled an intimate familiarity with the anticipation of mortality. This relentless, shadowy companion had etched its presence deep into the heart of his existence, much like the arid expanse of Texas had shaped the contours of his life. This profound recognition served as his own final salute to Heidegger’s “being-towards-death” and a stark acknowledgment of his own place within that austere philosophical landscape. The untamed expanses of the Texan landscape and the brooding mystery of the Black Forest were mere mirrors, reflecting the shared existential struggle of Howard and Heidegger in their respective corners of the world.

In the end, Robert E. Howard, in his life and through his pantheon of characters, embodied the core principles of Heideggerian existential philosophy. His heroes grappled with their own mortality, illustrating the concept of “being-towards-death.” Yet, they also shone with the defiance of the eternal flame, exemplifying the iron will to confront the dread of existence and carve out their own authentic paths. Howard might not have directly engaged with Heidegger, but his characters’ trials and tribulations reflect a deep engagement with themes central to Heidegger’s philosophy – making his tales an enduring testament to mankind’s relationship with the existential abyss.

Earlier today a friend mentioned that she had heard the term Sturm ud Drang on TV news.

With the connotation that it meant “tempest in a teapot”.

My response was that they have no idea what it means.

And then this evening I happened across this article.

I sent her some quotes and tried to convey that “I live, I burn with life, I love, I slay, and am content.” is closer to the point.