Cortés

Hernán Cortés was a character worthy of a Stevenson novel.

Born in 1485, just prior to Columbus’ first voyage, he experienced a childhood much like dozens of other larger-than-life characters in history, from George Washington to Teddy Roosevelt. That is to say: he was pale, sickly, and harbored unrealistic dreams of adventure. His parents, of impressive ancestry but less-than-impressive means, outlined a legal career for him, hoping that he would return the family to a position of wealth. However, Hernán hoped to follow in the martial footsteps of his father, an infantry captain who had led countless charges against the Moors. As he matured and became healthier, this conflict came to the surface; much to his parents’ disappointment, it became clear that he would not follow their desired path. Cortés was destined for a world not defined by statutes and contracts. In his youth, he was described as mischievous, arrogant, ambitious, energetic. Clearly his place was not in Spain, but somewhere wilder – somewhere he could impose his will upon the world.

In early sixteenth-century Spain, the obvious place for this sort of adventure was the New World. Fantastical stories about the untamed frontier had captured the Spanish public, and at only eighteen Cortés decided to make the journey to Hispaniola. Leveraging a family connection to Nicolás de Ovando, governor of the island, he became a citizen and began working as a simple notary in Santo Domingo. However, this position would not last; after volunteering for expeditions and distinguishing himself in the conquests of Hispaniola and Cuba, Cortés rapidly rose in the ruling class of the Spanish territories. By twenty-six he was secretary to the governor of New Spain, and magistrate of Santiago in the newly-acquired territory of Cuba.

The aggressive meritocracy which allowed Cortés to rise to power at such a young age is nearly unfathomable today, in our age of bureaucracy and corporatism. But this ruthless meritocracy was the primary draw of the New World in its early years. The same sense of do-or-die, intense competition would later animate settlers of the American frontier, civil engineers in the remotest jungles of the world, and test pilots for spacecraft; the lawless and unknown fringes always speak to enterprising individuals. The inherent meritocracy of these places is one of the many reasons that young men feel such a strong call to new frontiers; at the edge of the tamed and owned world, an ambitious individual can test himself against his peers and the world, risking everything in a truly open environment.

In the early sixteenth century, New Spain was this frontier – a budding nation where young talents like Cortés could test their mettle and quickly rise in stature. It was in this environment that Cortés excelled. His talents for leadership, rhetoric, and battle set the stage for the acts which would engrave his name in history.

These acts began in 1518, when Governor Velázquez made Cortés captain of an expedition to Mexico. Despite the trust conferred by this appointment, the relationship between Cortés and the Governor was one of extreme tension; Cortés had been romantically involved with two of Velázquez’s sisters-in-law and had recently married one, a situation which Velázquez resented strongly, despite his respect for Cortés as a leader. Thus, Cortés’ appointment as Captain-General was a begrudging rather than enthusiastic promotion.

After a few days, Velázquez’s personal vendetta overtook his professional consideration, and he changed his mind on the appointment. With Cortés’ preparations for the expedition barely underway, he revoked the charter and recalled the hopeful explorer.

But Cortés already had his sights fixed on Mexico, and he carried on undeterred, ignoring the Governor’s sanction. Hoping to preempt a more serious attempt at reigning him in, Cortés rallied six ships and 300 men in less than a month – an act of recruitment straight out of the pages of the Anabasis. This is where Cortés’ skill for rhetoric most clearly shines through; he proposed something impossible (even illegal), and yet men clamored to join his crew to seek glory in the untamed lands of Mexico. When Cortés’ fleet set sail in February of 1519, it was an act of open mutiny… but he continued nonetheless, captured by the potential for greatness.

When the conquistadors reached the shores of modern-day Mexico, they soon encountered another figure whose life deserves more attention: Gerónimo de Aguilar, a Franciscan priest who had partaken in an earlier, disastrous expedition along the Mexican coast.

Aguilar was one of just two survivors of this exceedingly unfortunate voyage, which had set sail some eight years prior. After a shipwreck, he and a handful of other survivors were taken captive by the Maya. There, most of them died of disease or were sacrificed. Before Aguilar’s scheduled execution, he and another (a sailor named Gonzalo Guerrero) managed to escape… only to be captured again, this time by a different Mayan tribe. For eight years he lived as a slave, learning the local language and customs. Guerrero did the same, eventually rising to a role of a war chief for the Mayan tribe that had captured both men.

In early interactions with the Yucatan natives, Cortés’ men heard word of their fellow bearded Spaniards, and made contact. They liberated Aguilar, and he immediately offered to join Cortés’ expedition as a translator.

During eight years of captivity and slavery, Aguilar had never faltered in his religiosity, nor in his observance of priestly duties. Upon meeting Cortés, he was able to correctly state the day of the week based on his schedule of prayer, which had never been broken. By this demonstration, Cortés knew that Aguilar had never “gone native”; that he was a Christian and a Spaniard still, and that he could be trusted to negotiate on his behalf.

Such was the caliber of men who set off for the New World.

Now with a translator and some initial skirmish successes, Cortés’ expedition reached Veracruz and claimed it in the name of the Spanish crown – officially placing the group under the jurisdiction of Charles V in order to circumvent any interference by Velázquez. This legal matter would not stop Velázquez from interfering later, but it gave the expedition a more official sanction as they prepared to march inland.

Through conversations with Aguilar and observation of the natives, Cortés began to understand the sheer scale of Aztec civilization, the vast hostile territory ahead – and therefore the Herculean task that lay past the sandy beaches of the Yucatan. His men, drunk on early success, would need motivation, commitment.

So, upon landing on the shores of Veracruz, Cortés made the decision that he would return “with his shield, or on it.” It was here that he issued perhaps his most famous order, one that has gone down in history as an example of pure commitment to one’s cause:

“Burn the ships.”

The conquistadors would return on native ships, or not at all. One can only imagine the impact of the scene, as the conquistadors’ only way home crackled and burned against the sunset, thousands of miles from home. Less than a battalion of men made camp on this strange and hostile shore, surrounded by enemies with no possibility of retreat.

The only way out was through. And Cortés certainly went through – he reached the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan in four months, a march characterized by constant battle and negotiation. This military conquest was, above all, an act of strategic genius; between powerful rhetoric and overwhelming force, Cortés’ detachment of 500 reached Tenochtitlan in a matter of months, recruiting on the way at least 1,000 native warriors.

Tribes encountered along the way were either subdued or turned against Aztec rule; the latter became an increasingly common occurrence as the Spaniards made their way toward Tenochtitlan. After repelling much larger forces in combat, Cortés would call for negotiation, where he made high promises: namely, freedom from the bloody yoke of Aztec rule. No more imposed human sacrifices, no more taxes paid to bloodthirsty shaman-rulers, no more taking of slaves and women. Instead, Cortés offered local freedom, fantastic cities, and eternal salvation. Perhaps some natives saw him as an emissary of Quetzalcoatl, with his new technology and strange religion; perhaps not. Either way, the Tlaxcala natives certainly saw his men as powerful fighters, and Cortés as a potent ally against the Aztecs. On the march to Cholula and then to Tenochtitlan, Cortés’ army snowballed in size and local support.

Historians tend to slander this element of Cortés’ expedition, pretending that he lied and cheated to exploit native divides. In reality, he simply offered a better deal than the Aztecs, with a strong assurance of success emphasized by the Spaniards’ shining armor and terrifying artillery. He had also gained the respect of many tribes, even those which initially opposed the Spaniards – something that is often difficult for today’s effete commentators to understand.

In battle after battle, the strange explorers proved themselves a formidable enemy – and not just due to their technology. While guns certainly made an impact on skirmishes with the natives, contemporary firearms were much more primitive than we tend to imagine. When guns and cannons were used in the New World, the conquistadors often managed only an initial salvo before the fighting became much more physical.

“The armor, the pikes, the Toledo steel blades, the discipline and know-how from decades of fighting the Moor… and above all, the bravery and daring…”

Bernal Díaz’s account of the conquest made it clear that while guns were useful, the Spanish almost always fell back to their swordplay and formation training. Even when “surrounded on all sides,” the Spanish repelled each charge, inflicting heavy losses with their superior tactics and arms. Díaz described these melees as “rather hot work”, leaving the bloody details to the reader’s imagination.1

It was in this “hot work,” these struggles of obsidian and steel, that Cortés’ soldiers proved their mettle – both to Cortés and to the Tlaxcala chiefs that witnessed their prowess. The Spaniard’s tactics, standard in Europe, were the result of centuries of brutal refinement, a crucible which had never formed in the New World. So, when natives launched dispersed, unarmored charges against the Spaniards, it quickly became clear that fighting was useless, and that allying with the Europeans would be far more advantageous than trying to defeat them.

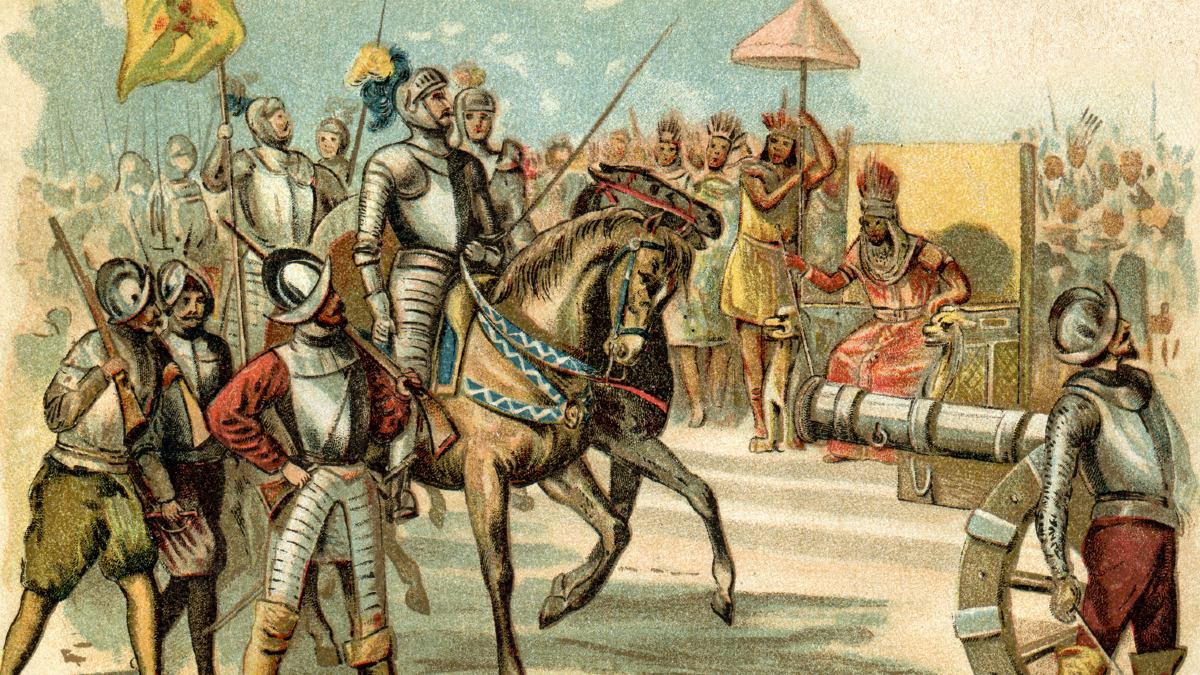

This was a strategy that the Aztecs themselves had been using for centuries: ‘We could crush you, but if you choose to join us instead of fighting, we’ll help you get rid of those other threats to your people.’ Cortés simply did it better. Thus, when he marched on Tenochtitlan to finally meet with Moctezuma, Cortés had behind him an army of Otomis and Tlaxcala fighters, led by Spaniards bearing arms which must have looked like magic to the Aztec capital’s populace.

Moctezuma cautiously welcomed the Spaniards into the city, hoping to keep them occupied for long enough to ascertain their weaknesses. This would prove to be a fatal mistake, as negotiations quickly broke down, with both groups becoming guarded in manner and speech. It became clear that the illusion of civility would soon be dropped. The only question was who would throw the first punch.

Cortés decided that he would act first. Despite being outnumbered and confined dangerously within Tenochtitlan – an island of some 200,000 people – he initiated a sudden coup, taking Moctezuma hostage. In one daring move, the Spaniards gained control over the entirety of the Aztec empire. Through bravery, cunning, and force of will, a mere 600 men had conquered millions.

~

However, this was by no means the end of Cortés’ struggle in Mexico. His feud with Velázquez soon returned to the forefront. Not long after Cortés took control over Tenochtitlan, the Governor’s fleet arrived in Mexico to arrest Cortés and his men for mutiny.

Cortés took some of his forces to meet Velázquez’s army, leaving only 200 men to control Tenochtitlan (and by extension, the entire Aztec empire). Outnumbered, outgunned, and running low on supplies, he nonetheless defeated Velázquez’s men handily.

In the aftermath, Cortés once again showed his rhetorical skill and personal magnetism: he convinced the force sent to arrest him to join him in conquering Mexico!

However, even with these additional men and supplies, securing the conquest of the Aztec empire would take many more months. Soon after Cortés’ newly-bolstered force returned to Tenochtitlan, Moctezuma was killed by his countrymen; in the chaos which followed, the Spanish were driven out by locals, in a wild battle mainly fought between a floating bridge and hundreds of war canoes. Díaz recounted it as a scene of pure havoc, something reminiscent of the Battle of Salamis – though with the Spaniards as the Persians, accosted on all sides by an ambushing enemy.

However, undeterred by their first and only true defeat, the conquistadors soon besieged, retook, and razed the Aztec city. When they marched on Tenochtitlan for the second time, they did so with a dozen brigantines and some 200,000 native allies, in what was likely the largest battle of the age.

The success of this siege finalized Spanish control of the Aztec empire, and Cortés received official permission from Charles V to rule this new territory. As governor, he went on to rebuild Tenochtitlan as Mexico City, converted thousands of natives to Christianity, and tamed the fractured world of sixteenth-century Mesoamerica in the name of the Church and the Spanish crown.

~

In order to settle political disputes with his countrymen, Cortés returned to Spain twice after his conquest of Mexico. Upon his first visit, he was received by Charles V with honor and distinction; the emperor granted him a coat of arms, official titles, and vast property in the new territory.

But on the second visit, he went unrecognized. After pushing his way through a crowd to speak with the King, the monarch did not recognize him, demanding to know who the man accosting His Majesty was. “I am a man,” Cortés answered, “who has given you more provinces than your ancestors left you cities.”2

This is the Cortés that the history books should remember.

Footnotes

1Díaz, Bernal, tr. by Lockhart, John Ingram (1844). The Memoirs of the Conquistador Bernal Diaz del Castillo, Written by Himself, Containing a True and Full Account of the Discovery and Conquest of Mexico and New Spain.

2Folsom, George (1843). The Dispatches of Hernando Cortés, the Conqueror of Mexico, addressed to the Emperor Charles the Fifth, Written During the Conquest, and Containing a Narrative of its Events.

My last name is Cortes.

Amazing read.

I would love to write a small serie of adventure novels about Cortes. Aside from the 2 books mentioned in the footnotes, are there more books you recommend to investigate about Cortes life and adventures?