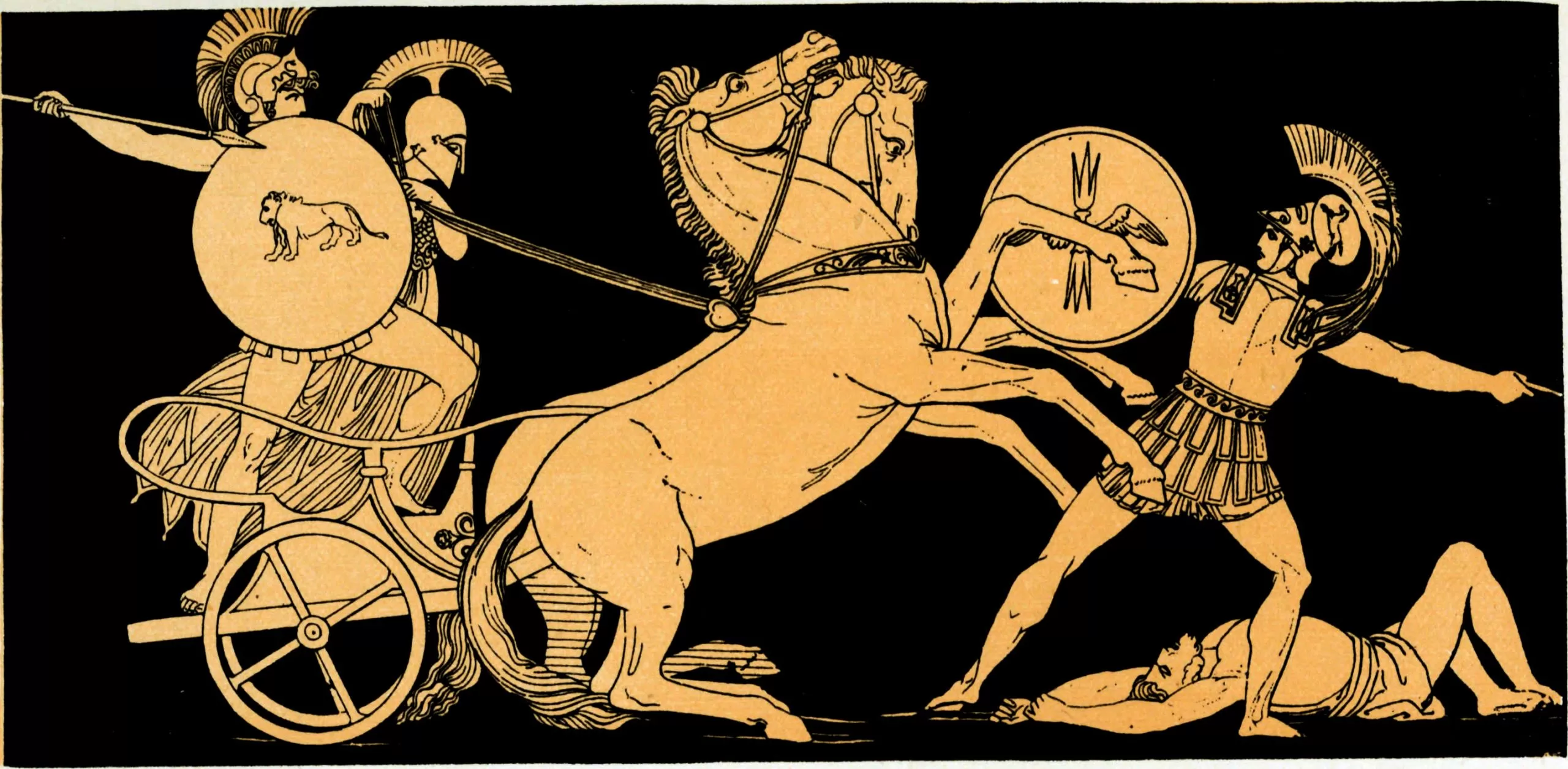

The Greek Mythical Ages are the most interesting. The Golden Age fell from Prometheus sharing fire with man. The Silver Age seems worse than the Bronze Age in many ways. It is unique that Greek Myth has five Ages — Vedic and Roman accounts both lack the Heroic Age, the only Age said to be better than its predecessors. The Heroic Age started with the Mycenaean Culture and ended with the Trojan War. Understanding the Heroic Age is the key to freeing the Hero subsumed in the Trader.

The Vedic Yugas may have longer timelines than the Greek Mythical Ages, and the Romans mistakenly tried to combine them based on similar forms. It is important to remember that this era was around 1600 to 1100 BC, long before the Hellenistic Period or Rome. It is also likely that this culture was a synergistic combination of various peoples from the north and south — likely encompassing both remnants of Corded Ware, Yamnaya, and Bellbreaker cultures fused with Minoans, among others. Proto-Indo-European elements at this time were already many thousands of years after the fracture from whatever origin was shared between Proto-Indo-European offshoots and India, with other PIE offshoots layering in.

Many miss that the “Greeks” of the Iliad encompassed many demarcated peoples with changes over hundreds of years, likely influenced by advanced trade civilizations south of them, which also seeded their fall. By the time of the Trojan War, the Peloponnese was inhabited by Achaeans, and the Dardanians ruled Troy. Location on the Eurasian continent does not necessarily denote ethnos or new ethnogenesis because many were in constant flux and movement, which is common with more complex groups.

Helen of Troy was said to have had three sons with Paris, who died, but one daughter named Helen is unaccounted for. A woman named Hellen birthed Dorus, the founder of the Dorian people during this exact same timeframe — this represents surviving Dardanians, and there are other mythological accounts of surviving lines I will get to in the next article to show a common theme. The Dorians later conquered mainland Greece during the Greek Dark Ages. They founded post-Lycurgian Sparta, Macedon, and many other Greek nations in the archaic period as a Spiritual atavism of the lost Heroic Age. In fact, Athens was, during that time, the only non-Dorian part of mainland Greece.

It is fateful that Lycurgus founded his precepts in the Iliad itself, reviving the Heroic natural order without over-litigation, individual aggrandizement, or material decadence, allowing the Hero’s spiritual synergism to continue. Bonding his people to his life-giving laws would take more than words on paper because over-litigation only creates a Stasis of Forms. Lycurgus had them swear to his precepts until his return from visiting the oracle but instead sacrificed himself to bind them by blood to his people. The Life Giver enacted a culture of self-sacrifice that transmuted the death sentence of the Iron Age back into an isolated form of the Heroic Age for another half-millennium, even if not like the original Confederation of the Mycenaeans.

When Plato wrote of a Philosopher King, he was writing of the past already embodied in post- Lycurgian Sparta — the unique civilization of the Iron Age that fused the best aspects of Barbarism and Civilization. The archetype of Lycurgus was unique, and it is no accident that the Life Giver enabling Heroic cultural synergism is not the archetype of a warrior or general. His precepts allowed their living culture to change over time without over-litigation that strangles people in a mechanized form applied to all as interchangeable parts. This starkly contrasts the negative feedback loop in the Iron Age of the Hero subsumed in the Trader — a warrior rising up for a short timeframe only to further along the same zeitgeist. The self-sacrificing philosopher king destroys the age he comes into and allows a warrior culture to grow synergistically. The self-aggrandizing warrior, though great, is part of the curse of his times because he is meant to uphold a culture created by the Life-Giving King of Kings.

Napoleon was an amazing man and warrior, there is no doubt about this, but he did not change the age — he was sacrificed to it, and his life force propelled it unknowingly. Within the zeitgeist, we see the warrior constantly trying to break the chains of the age by over-blanketed litigation to combat huge disparities and decadence — the Stasis of Forms creates a need for increasing itself. Barbarians and warriors picked up a fragment of the Heroic Age — trial by combat and dueling opposing over-litigation. Napoleon had reverence for these heroic traditions along with Western counterparts of their revolution since the US even legalized dueling until the Civil War. The last gift Napolean commissioned for his son was dueling pistols. His heir’s inheritance ending up in a merchant’s museum is a microcosm of the Hero subsumed in the Trader of the Iron Age along with his lasting legacy of legal code.

Many constantly look to the archetype of the warrior to save us again and again without realizing that they are unwittingly strengthening our chains. Yes, they are impressive men who inspire a desire for the return to the Heroic, but this does not come in isolation, which the Stoics also missed. While this warrior archetype does transmute the death throes of his people for a short while if he is self-sacrificing or destroys his people if he is self-aggrandizing, he does not end the zeitgeist. The warrior/general archetype upholds any order (and not all order is heroic). He does not destroy the age or create a new form of the Heroic Age — the general that charges into battle in front is a Leonidas, not a Lycurgus. Though great, he is not meant to be the King of Kings.