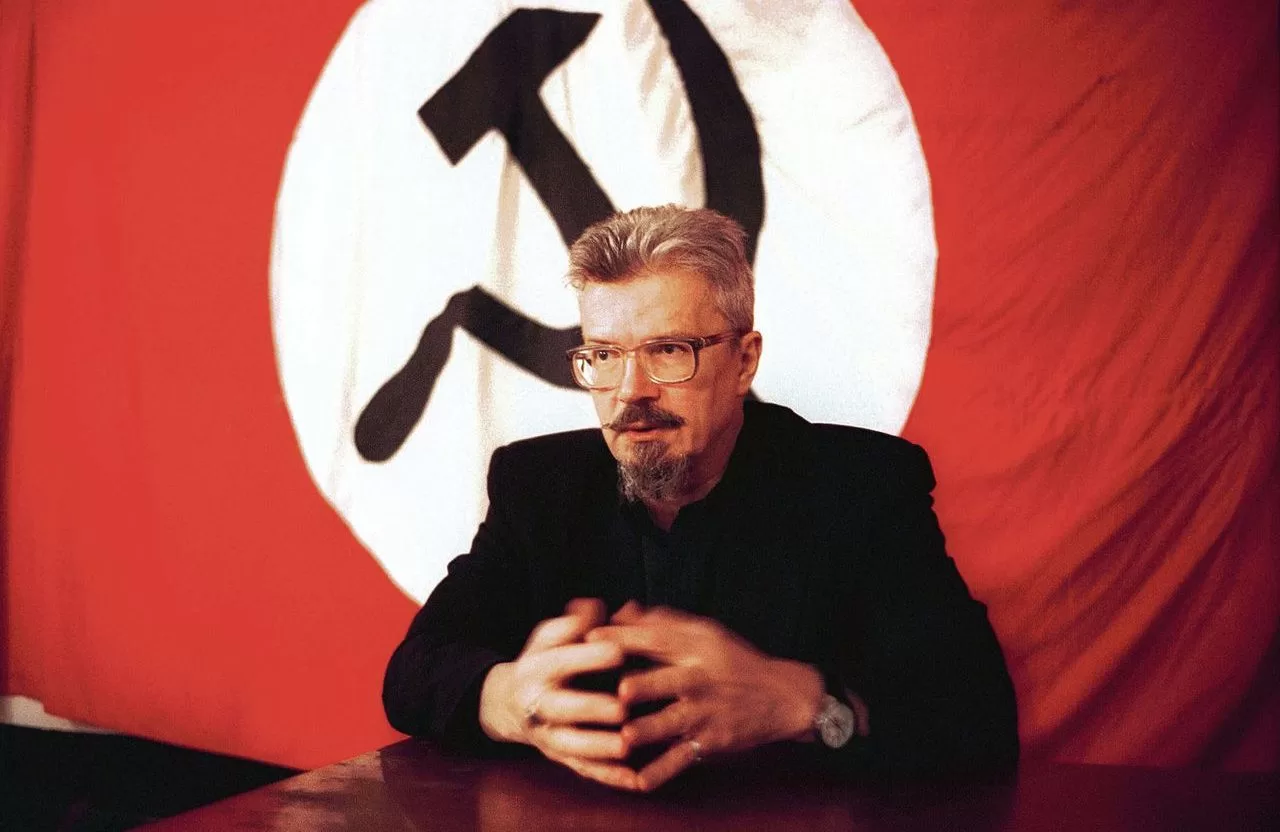

The majority of the New Right is at least rudimentarily familiar with the philosophy of Alexander Dugin. However, Eduard Limonov, who worked with Dugin for decades, is almost absent from the discussion. Nevertheless, he too developed an interesting philosophy that is certainly worth a look.

The first fundamental thing that can be said about Eduard Limonov is that fashion, youth culture, politics, and philosophy are inseparable in his work. His National Bolshevik Party was thus not meant to be a party like the AfD (Alternative for Germany) but rather a mix of political party, ‘punk group’, and avantgarde. This influence also partially spilt over into the early texts of Alexander Dugin and is, for instance, a reason why Dugin’s ‘Arctogea Manifesto’ concludes the ‘list of most significant philosophers’ with John Lydon from the Sex Pistols.

Direct Predecessor of the Identitarian Movement

The second point is that Limonov uses an extremely personal, emotive style that quickly builds a closeness with the reader and therefore often uses tools like anecdotes. Hence, Limonov’s style is the complete opposite of Alexander Dugin’s, who often writes so academically dryly that one only grasps his meaning after the third reading.

The downside, however, is that Limonov did not really think through much of what he demanded. This is particularly noticeable on the topic of the economy. For instance, he quite rightly complains that work in principle is ‘rubbish’ and that workers have to lead a dreary life as ‘wage slaves’. Yet he does not mention automation but instead suggests at one point that in order for people to work less, there should be a voluntary agreement to consume less.

Libertarian Totalitarianism?

Limonov’s fundamental thesis is that he views modernity as a process in which the world is increasingly technologised, quantified, and regimented in a way that can be easily controlled from above — similar to Ted Kaczynski, René Guénon, Theodor Adorno, and Martin Heidegger. This process makes the world more efficient and safer. However, it also ensures that the world becomes ‘more boring’; man becomes more alienated from his life and from others, and traditional systems such as the family are devalued, undermined, and degenerated into mere instruments of state power. Directly tangible effects of this process are, above all, the exploitation of workers, as well as the modern school system, which only drills children into obedience.

Hence, the choice between capitalism and communism plays a secondary role. Capitalist states would preach the free market but not live it. Instead, the same ‘control structures’ have been established in the West as in communism, with the difference that the West, instead of the state, prefers some international mega-corporations and destroys the economic freedom of all others to their advantage.

A consequence of this is that there are private companies in the West but, with few exceptions, no visionary entrepreneurs who shape the company through their own spirit. Instead, companies have devolved into stock corporations, whose ownership is so fragmented that it is no longer clear for whose benefit a company still exists.

Dictate of Economic Efficiency

The Great Man theory, on the other hand, assumes that some outstanding individuals influence the course of history through their ideas and actions, while the masses are just a ‘lethargic heap of disinterested fools’ who only jump onto a ‘train’ as followers.

This special individual who directs history is the radical outsider apart from the masses. He does not care what the common people think of him and instead lives only according to what he believes to be right. The reference to Nietzsche’s Übermensch (overman) is obvious here.

Culture-Creating Geniuses

According to Limonov, these people represent the precursor of the Nietzschean Übermensch described above. And such a group of pariahs, according to Limonov, are the punks to whom he particularly addressed himself — but at the same time, all kinds of radicalism, whether left-wing, right-wing, religious, or anarchist in motivation.

This could now be interpreted very individualistically. However, this is not entirely true. The individualism that is typical of Western states today is, for Limonov, a sick consequence of modernity, born out of fear of syphilis and other diseases. Instead, humans need the community to unfold their potential and freedom. Limonov develops a concept that roughly reminds one of the typical New Right communitarianism and communes of left-wing anarchists and hippies, as well as Jack Donovan’s idea of the ‘new barbarian tribes’. One should imagine the ideal commune in the Limonovian sense as a kind of large family where everyone is either related or married to each other.

Everyone Should Be Married to Everyone

This demand for free love was the main reason why Alexander Solzhenitsyn was hostile towards Limonov. Indeed, from a Traditionalist point of view, this can be delicate. However, Julius Evola has referred to both marriage and the orgy as legitimate traditional forms of sexuality and partnership. Terence McKenna, who, as a hippie, advocated free love and drugs, had a worldview very similar to Traditionalism.

However, Limonov saw the fundamental prerequisite for a community as the willingness to fight for one’s loved ones and family and possibly to die for them. Limonov formally calls this conscription. However, typical of his anarchist manner, he rather means the idea of a militia, as it is realised in the USA, particularly through the Second Amendment. According to Limonov, when individuals are allowed to own weapons and organise and defend themselves, it ensures that they develop a healthy mistrust of central authority.

The Collapse of Globalism

This would be the endpoint of modernity and the centralised state. In the ensuing chaos, people would reorganise themselves into nomadic groups and small village communities. A variety of voluntary associations with the most diverse cultures and ways of life would emerge, living freely on their own. And these would organise themselves like former principalities into a new ‘feudal’ Russia.

It is evident that Limonov’s philosophy is much more chaotic and ‘destructive’ than that of Dugin and most of the New Right. Therefore, it will not be an option for many to adopt his system wholesale. However, Limonov managed to develop an extremely dynamic philosophy from a Traditionalist or conservative point of view. And precisely because many conservatives are sinking into prudishness, humourlessness, philistinism, and hostility to life, it is worth looking at Limonov’s philosophy of extreme, chaotic freedom as an antidote.

Limonov was an utter, disgusting degenerate. How anyone can take that clown seriously is just beyond understanding.