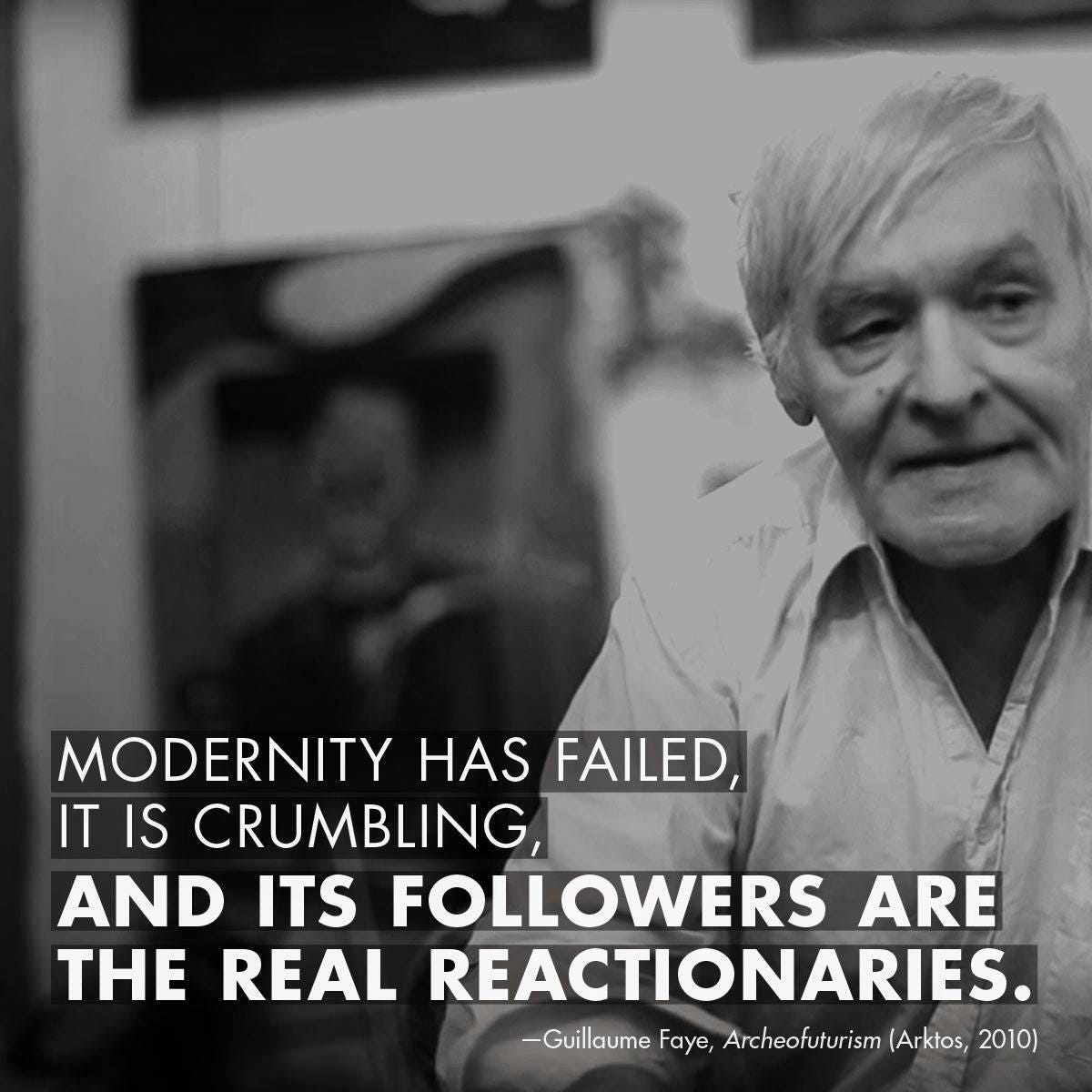

In his seminal work Archeofuturism: European Visions of the Post-Catastrophic Age (1998), the French philosopher Guillaume Faye (1949-2019) posits that radical thought is a thought aimed at the foundation of things and phenomena, capable of initiating an ideological storm and leading to a re-evaluation of the values of the era in which it was born.

Such a definition fundamentally contradicts the popular perception of the radical as an ‘extremist’ who reflects a thoughtless and uncompromising adherence to a particular idea, usually entirely utopian. This modern perception of radicalism as an irrational pursuit of meaningless rebellion, devoid of deep existential content, can, of course, not be considered satisfactory. Radicalism, as depicted by the adepts of modernity and the Enlightenment, is skeletal and dogmatic — essentially, a caricature of a genuine intellectual revolution.

Faye, on the other hand, points out that radical thought is heterotelic — it contains within its essence an internal dynamism, allowing for a diversity of outcomes and results and not affirming anything unequivocally. According to the French thinker, the arsenal of radical thought in the twentieth century includes Friedrich Nietzsche, Julius Evola, Martin Heidegger, Carl Schmitt, and Guy Debord. These thinkers aimed to re-evaluate the dominant worldviews, creating their own critical concepts and in no way sparing the modern world. They called for a radical restructuring of the very models of thinking about it. In this lies their exceptional value both for contemporaries and for ideological successors.

‘Philosophising with a hammer’ paved the way to a new sensation of life, a new perception of the past, the present, and the forthcoming. True radical thought is an attempt to feel out new (or well-forgotten old) types of world sensation, capable of lending strength in the present and preparing for the future — ‘for that which is to come’.