Today in the West, we find ourselves on a dangerous precipice. Many of us see our nations changing in ways that are destructive if not terrifying for the direct threats currently leveled at our ethno-culture. We find our means to speak out in defence of our very ethnic existence curtailed by social factions pushing the notion that recognizing our own unique status as an ethnic group and wishing to preserve and protect our ethno-culture is somehow racist. As is natural, a reactionary movement has burst onto the scene, known in America as the ‘Alt Right’ (a social phenomenon); in Europe, meanwhile, any individual or group that bears any semblance of ethnic pride or nationalist leanings is labelled ‘far-right’. Any time a group of people is singled out and marginalized, unless the domineering force has managed to subdue and subjugate the group entirely, there will be a reactionary rebellion.

Contents

Recognition of the need for nationalism is growing throughout the West on both sides of the Atlantic. The election of Donald Trump demonstrated that ethnic-Europeans in the United States very much reject the liberal direction our country has taken. Some level of nationalistic revival has occurred here in the States, demonstrated by Trump’s ‘Make America Great Again’ slogan. However, the second half of the 20th century saw Western nations overrun with cultural Marxist ideology that have eroded the cultural continuity that America once had. And, while conservative Americans look at liberal Europe with disdain, America’s situation is every bit as precarious due to demographic shifts thrust upon us by cultural Marxist social engineers. Now that the emotional outburst of the reactionary Alt-Right has broken onto the scene, it is important to dig deeply into cultural histories to evaluate who we are as a people and what it is that we want. For, a movement based solely on reactionary emotion will be hollow and can fizzle out as quickly as it began. Thus, it behooves us to look closely at the Age of Nationalism in Western history to find grounding and direction.

My biggest criticism of the Alt Right is that it seems largely rooted in emotional reactivity. It arises in a generation of individuals rightly rebelling against the liberal indoctrination which demonizes them, but they themselves lack any grounding in the ethno-culture they claim to be standing up for. In fairness, this is not necessarily the generation’s fault. Our societies have seen a steady decline in cultural identity ever since the mid-20th century. Hollywood, news media, and academia seem to be dominated by, essentially, a cabal of Bolsheviks who are hell-bent on tearing down Western cultural foundations. These people have used their positions of influence to bring corrosive messages to impressionable young adults and manipulate them into thinking that ethnic-displacement is somehow ‘social justice’. Therefore, we’ve now got a fresh crop of young ‘white people’ who recognize the injustice of the liberal attacks on whites, but who lack the grounding in their own history, heritage, and culture that ancestors had just two or three generations ago. Looking toward the nationalist movement of the 19th and early 20th centuries can give us guidance on how to proceed. For, in many ways, we are currently living in a dystopian nightmare brought on by the Marxist demolition of European ethnic-nationalism.

The Romantics’ Rejection of Urban Values

In order to understand what ethnic-nationalism means, we must look back in time to the 19th century. Remember that the prior century had seen the overturning of the traditional order. The American and French Revolutions at the end of the 18th century forever crippled the institution of monarchy in the West. The Industrial Revolution in the early 19th century drastically changed life for a majority of Westerners. Where the economy had traditionally been largely agrarian-based, mechanization meant that fewer hands were needed to run farms. Simultaneously, the boom of machinery meant that factory work became a mainstay of working class employment. In addition, locomotion became much easier with the railways making long distances more easily traversable by land, while steamships made transatlantic crossing quicker and more affordable. Those physically able to go where the work was, did so. Thus, urban centers boomed in both Europe and the Americas.

The Romantic Movement was a reaction to, and in many ways a rejection of, the values of the Enlightenment and industrialization. Urbanization had brought with it filth, poverty, crime, squalid living conditions – the poor standards of living highlighted by Charles Dickens in his novels. But the movement to cities and emigration abroad was affecting European society in another way. Observers today often note that mass migration adversely affects the home countries of migrants due to what is called ‘brain drain’. This is effect on a home-nation where its talent is lured away to other countries and put to use overseas instead of at home. A different but comparable phenomenon affected Europe in the 19th century. The depopulating of the countryside meant that Europeans were no longer engaging in age-old customs that had previously gone on since time immemorial. Agriculture-based societies are always much closer to both nature and their ancient root culture. Thus, many beliefs and practices that had been ongoing since the Pagan Era were still in place in rural Europe. In many ways, these beliefs, practices, traditions, customs, stories, and songs are what had always made up the national character of Europeans.

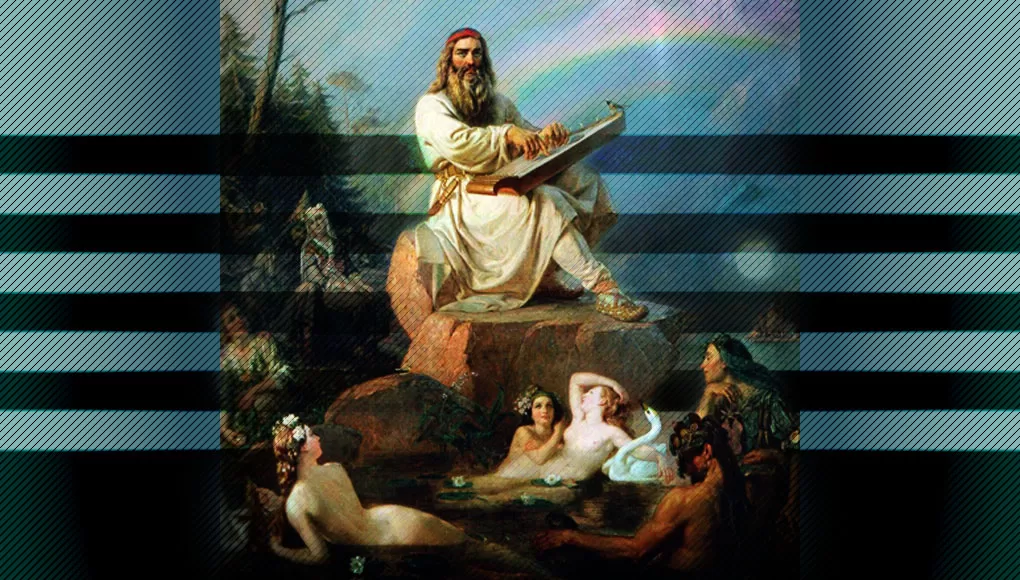

The Romantic Movement was comprised of people who saw the value in rural life and recognized that something beautiful was on the verge of being lost. Thus, creatives like poets and painters poured their energy into celebrating the beauty of nature and of their own ethnic heritage. In the midst of this momentum came the birth of the discipline of Folklore. Recognizing that it was the people who carried on the culture, and that these people were losing what had previously been thought to be unloseable, many individuals took it upon themselves to traverse the countryside and record the beliefs, customs, and stories of their own folk before they were lost forever.

The Building of Nations

Although sense of ethnic identity and loyalty to one’s folk is nothing new, the concept of ‘nationalism’ in the modern sense was born in the 19th century. As mentioned, revolutions of the prior century (and yet more that would ensue) overturned the traditional order of monarchy. Medieval Europe consisted of kingdoms, duchies, principalities, and at times, of empires. These terms for a country are obviously built upon the old hierarchy of nobility, wherein one’s direct allegiance was to the noble overlord – a remnant of the medieval model of feudalism. While some modern nations, like the United Kingdom, can claim a centuries-old establishment, other European nations like Germany and Italy are very new. In those regions, kings of smaller states, dukes, princes, barons, etc., still held autonomous control over their land. The unifications of Germany and Italy were momentous events, and they did not occur quickly or without controversy. Indeed, Bavaria, as an autonomous kingdom of its own, did not wish to join the new state of Germany. And, to this day there are cultural dissidents in Northern Italy who see themselves as culturally distinct from Southern Italians. This is why regional independence movements spring up around Europe here and there even now – which is not to say that unification was a negative thing, but simply that, like all political events, it was not completed without controversy and arguments both for and against.

In addition, many nations that we now think of as culturally unique and autonomous had long been subjugated to other nations. For example Finland is ethnically distinct from other Scandinavian countries that have a Norse mytho-linguistic background (in the Teutonic branch of the Indo-European language family), whereas Finland is of the smaller European language family, the Finno-Ugric language group, which is not of Indo-European origin (it is related to the Saami and Hungarian languages). Many Westerners today forget, or simply do not know, that Finland was a vassal state of Sweden for some 600 years until it won independence at the outset of the 20th century. Likewise, the nation of Norway had been under Danish rule for over 400 years, only gaining independence in the early 19th century. But, even more people are not aware of the important socio-political role that folklore played in the establishment of these and other nations.

Returning to the example of Germany, the socio-political climate surrounding German unification of the 19th century has been forgotten in recent years. German speakers in these disparate smaller kingdoms and duchies sought to unite into one nation for the kind of protection and other benefits that a nation-state can offer. So while Finland and Norway were seeking to separate from a neighbouring governing entity, Germans were seeking to unite ethnic Germans into a single state. These political initiatives were occurring simultaneously with the cultural movements discussed above. And, unlike today, politics, culture, and ethnic identity were not seen as mutually exclusive. Thus, the culture of the ‘folk’ was celebrated and used to remind people that they possessed a unique ethnic identity worthy of distinction and autonomy. In Finland and Norway, this conception was used to differentiate them from their powerful neighbors as their own unique cultures deserving of their own governing authority; while in Germany, celebration of folk culture was used to remind German-speakers in many small states that they do, indeed, share one unified German culture.

Nurturing Folk Identity

One important aspect of nationalism is the concept of ‘folk’. In an age where certain agendized factions have orchestrated the planned demographic change of Western nations and subsequently used their cabal over academia and media to repeat the messaging that ‘we are all one race’ and ‘white people have no culture’ to the point of mass psychological conditioning, is it any wonder that no concept of ‘the folk’ exists anymore? But, in the past, there had been a recognition that people who share genetic and cultural similarity to oneself were their own folk. This is an extension of the conception of ‘kith and kin’ and ‘clan and tribe’. Modern historians have tended to look unfavourably on ethno-nationalism and to deride it as somehow ‘racist’, when these are the very concepts by which virtually all East Asian nations and Arab nations, not to mention Israel, understand themselves today. It was the goal of reviving and celebrating their own folk that was the impetus for Finns and Norwegians to cast off others who sought to rule them; and recognizing shared folk culture allowed small German states to unite into modern Germany.

Intentionally produced disconnect from identity, culture, and heritage, has rendered a generation of ethnic-Europeans who lack an interest in their ethnic culture while it has been replaced by various surrogates like vapid materialism or various American cult-like religious sects which, like Islam, place a universalist ideology over ethnic identity. While European society was largely Christian in the 19th century, the mindset of Europeans was far less ethno-masochistic than what we see today. Whereas European nationals are socially conditioned with very liberal values, European-Americans are conditioned to view history with a revisionist lens that disparages indigenous European ‘pagan’ culture. The original European nationalists held a worldview that is in direct opposition to both of these forms of modern ethno-masochism.

In his article ‘Norwegian National Myths and Nation Building’, Dag Thorkildsen explains that the very concept of a nation is ‘related to birth and descent’ and ‘the classic idea of a homeland’, and explains that, unlike today, that in the 1800s ‘patriotism was a virtue of the inhabitants’, (p. 263). He discusses the ‘ethno-symbolic’ view of nationalism which ‘stresses the importance of symbols, myths, values and traditions in the formation and persistence of nationalism’, (p. 264). But, when looking at European nationalism with even a cursory glance, we find it is the ancient, primal symbols of European culture that are always the images used in any successful nationalist movement. And, likewise, the myths always used to encourage ethno-national identity are always indigenous European myths and legend that originate in the land of the folk themselves; i.e. European pagan mythos and symbolism are always drawn on to revitalize our folk spirit. Indeed, the European nationalist parties and movements with the greatest momentum today are still using ancient European runic symbols and imagery.

But the area that was especially useful in engaging the hearts and minds of the folk, uniting them in their shared heritage, and infusing energy into political nationalism was the cultural emphasis on indigenous European folk culture. Thorkildsen says that while the political movement was underway, ethnologists and folklorists ‘searched for folk legends, fairy tales, folk songs and folk music’, (p. 266). Thoskildsen explains that in order for it to be viable that ‘Christianity needs to be national’, and that, rather than a homogenizing of world cultures under a universalist form of Christendom, Norwegian nationalists rather believed that ‘the spirit of the Creator manifests in the spirit of the people’, (p. 267). In other words, the indigenous ethno-culture of a folk-group should not be rejected by Christians, but rather the Christians should see the value in their own pre-Christian culture because the manifestations of their own culture are valid a manifestations of the divine. Therefore, we see European Christians in the 19th century embracing a synthesis of distinctly European culture (rooted in our pagan past) with Christianity – whereas today’s would-be nationalists in the United States have been recruited into a problematic version of Christianity that shuns and rejects our indigenous European roots. By the same token, many modern European nationals often seem disconnected from both ethnic-identity and any semblance of spirituality whatsoever.

To further emphasize the point, Thorkildsen explains that loyalty to national identity ‘does not primarily stem from religion, but from the nation’s heroic and glorious history, from the people you are related to, and from the emotions – in other words, the love of country and nature. The role of Christianity is reduced to a part of the historical and cultural heritage’ (p. 270). This is important because, as he asserts, ‘cultural nationalism cannot be held separate from political nationalism; they are entwined one with the other’, (p. 270). Yet, here in the United States, there seems to be an emphasis by political elites to drive home a universalist religious identity intermixed with American conservative politics rather than any emphasis on our ethno-cultural roots – and European politicians are now denying that Europe has any ethnic identity at all.

In the case of Finland, we see that indigenous Finnish culture played an integral role in Finnish nationalism. In his book, ‘Folklore and Nationalism in Modern Finland’, William A. Wilson asserts that Finland likely would not have achieved independence at all had it not been for the publication of the Finnish mythic epic, ‘The Kalevala’. Wilson gives us some quotes by others who have studied Finnish nationalism:

- ‘Finnish nationalism as a purposeful doctrine was formulated largely under the inspiration of folklore studies’.

- ‘The Finnish nation was conceived in and born of folklore’.

- ‘The Kalevala has been and still is the abode of the Finnish national spirit’.

- ‘[The Kalevala] can be called the independence book of the Finnish nation’. (Wilson, ix)

But, what may be even more revealing about the processes behind their nationalist awakening is the cultural conditioning that Finns were subjected to. As explained above, Finns descend from a completely different ethnic background than other Scandinavians. Swedes, Danes, and Norwegians share a Norse-Teutonic cultural background with closely related languages and mythos. The Finns hail from a Finno-Ugric mytho-linguistic group and are genetically distinct from Norse. Under Swedish domination, educated Finns were conditioned to speak Swedish and even identify ethnically as Swedes. According to Wilson, Finns began to speak in terms of ‘we Swedes’ and ‘our ancestors, the Goths’. The Goths were a Norse-Teutonic ethnic group, neighbours to the Finns but distinct from them. This is essentially the same kind of erasure of identity that we see elites pushing on ethnic-Europeans today. Today we see conditioned drones parroting ‘we are one race, the human race’ and ‘I am a citizen of the world’. But, this is nothing new. Prior to this, our students have had it droned into their heads that ‘European culture has Greco-Roman origins’, and that our values are ‘Judeo-Christian’. As scholar Stephen Flowers points out in his ‘The Northern Dawn: A History of the Reawakening of the Germanic Spirit’, Northern European culture has its own distinct culture; moreover American government is based on English common-law which has Anglo-Saxon, Germanic, origins. The notion that Northern European culture (and thereby, the colonies founded by Northern Europeans) owes its existence to other cultural origins is not only incorrect and ethnically offensive, but it is an example of this kind of cultural conditioning that attempts to erase an ethnic group’s identity in order to brainwash a population into loyalty to the dominant cultural colonizer.

A Way Forward

The missing element that is essential for a true ethnic-revival is to follow in the footsteps of the original nationalists and promote cultural revival alongside our political struggle. This is, of course, much easier for European nationals who are still living on their ancient home soil. Europeans have inherited a landscape dotted with ancient sacred sites, cultural folk festivals still appear throughout the year far and wide, and regional cultural practices still thrive. Americans, and others in former European colonies, do not have such so easy a path to a meaningful ethno-culture now that our national demographics have been so drastically altered. But all is not lost.

Revisiting the points above, it is important to elevate the status of ethnicity. Americans have been led down a destructive path of ethno-masochism which demonizes and belittles our European cultural origins. There must be a concentrated effort to understand that the divine is manifest in the culture of the people and therefore a syncretic fusion may occur between the Christian mindset and our indigenous European roots. European nationals seem to have no problem with this understanding. Americans must take a hard look at the version of religion that has been pushed in this nation and start questioning the motives behind it.

But what to do when a nation such as the United States does not share one unified cultural origin? Scholar Jennifer Cash discusses the role of folklore in nation-building in her book, ‘Villages on Stage: Folklore and Nationalism in the Republic of Moldova’. Although she seems to make every effort to take the typical liberal academic approach which seeks to separate folklore from ‘the bad kind of nationalism’, her thesis focuses on the role that folklore played in the building of national identity for the new nation of Moldova. The reasons for a ‘multi-ethnic’ society in Moldova are different than those bringing about the same results in the West today. Cash explains that ‘in the past 250 years alone, the Ottoman and Russian empires, Romania, and the Soviet Union have all governed portions of the territory now encompassed by Moldova’s borders’, (p. 23). We know that the Ottoman Empire and the Soviet Union both made excessive effort to acculturate the regions they subjugated. Moldova’s crossroads location, history of foreign domination, and status as a new autonomous nation all created a unique problem for identifying what is Moldovan cultural identity.

Cash reminds us that ‘folklore, in its guises as academic discipline, subject matter, and performance genre, has been implemented in nation-building and nationalist movements since the eighteenth century. During the twentieth century, states of all political orientations used folklore … to build images of the nation. … Folklore, as is especially visible in folkloric performance, identifies the content of national identity, asserts dominant values, constructs relations with other nations, defines boundaries for including social groups within the nation and excluding them from it’, (p. 12). Well, this is very revealing considering that the West today lacks any cultural interest in our own folk culture and is concurrently grappling with lack of cultural identity whilst being simultaneously told that borders are racist and all groups are welcome. In the case of Moldova (and other examples in history), a cohesive sense of ethnic identity was encouraged by a ‘state-wide system of folkloric festivals’ which are ‘responsible for constructing relations of hierarchy between the village, the region, and the nation’, (p. 18). Therefore, Moldovans dug deep to find distinctly Moldovan culture and then made the effort to celebrate it, thereby distinguishing and elevating their own ethnic identity.

America’s holiday traditions were largely based on ancient European folk customs. Today our town squares have to fight for our Christmas trees, a direct attack on European Yuletide folk custom. We see less and less town-sponsored Easter-egg hunts. And, in my formerly 90% ethnic-European suburban neighbourhood, the decimation of the presence of white children (while the demographic prevalence of non-white children has greatly increased) has rendered Halloween trick-or-treating virtually non-existent. One hundred years ago, most American towns and cities still erected May poles at May Day. Now the occurrence is near-extinct. All of the examples listed here stem from Northwestern European cultural origins and were so widespread in the United States due to the truth that we were once essentially a Northern European ethno-state. Now that the ‘melting pot’ has done its job, our identity has literally been melted away, and it shows in the erosion of our own folk-culture.

If we, ethnic-Europeans, wish to survive, it is crucial that we double down on our ethnic identity. European nationals must assert their right to embrace, preserve, and protect their indigenous cultures just as East Asians and other ethnic groups do today. For ethnic-Europeans in the colonies, the roadmap may be more difficult – especially in the United States where ‘white identity’ is simultaneously co-opted by a both liberal aggression and problematic form of religion which intentionally severs us from our ethnic-European origins. Americans and other colonials must do some serious soul-searching. European culture clubs and social groups should become a mainstay in white-American society. We must reject cultural Marxism on both sides of the Atlantic, and American Christians must seriously consider how they can synthesize their faith with our ancient ethnic heritage. Self-hate and erasure of culture is how ethnic-genocide is completed, and it has been long underway in the West. The answer is a double-fisted grasping-on to our indigenous European ethno-cultural roots, just as all ethnic groups should do, and nurturing a love and celebration for our own unique ethnic identity. As the first nationalist movement demonstrates, our ancient heroes are ready and waiting to sound the trumpets of ethnic revival! All we must do is look to our own past, embrace it, celebrate it, and let the voices of our past guide us toward the future.

Bibliography

Blanning, T. C. W. The Romantic Revolution: A History. New York: Randomhouse, 2011. Print.

Cash, Jennifer R. Villages on Stage: Folklore and Nationalism in the Republic of Moldova. Zurich: Lit Verlag, 2011. Print.

Flowers, Stephen. The Northern Dawn: A History of the Reawakening of the Germanic Spirit. North Augusta, NC: Arcana Europa Media LLC , 2017. Kindle Book.

IHMS, M. Schmidt. ‘The Brothers Grimm and Their Collection of ‘Kinder und Hausmarchen’’. Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory 45 (1975): 41–54.

Thorkildsen, Dag. ‘Norwegian National Myths and Nation Building’. Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte 27.2 (2014): 236–276.

Williamson, George S. The Longing for Myth in Germany: Religion and Aesthetic Culture from Romanticism to Nietzsche. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

Wilson, William A. Folklore and Nationalism in Modern Finland. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1976. Print.

[…] View Reddit by Swillyb0b – View Source […]

There’s so much truth and common sense spoken in the words of Carolyn Emerick that only a people gone mad and heading towards even more madness cannot stop to listen to them.