Family Predates State

The foundation of social order is the family, which precedes the State, being a society in microcosm. Consequently, the family has social rights and duties that are independent of the State.1 Private property is the means by which the father provides for his family, and ensures the well-being of his offspring – those who ‘continue his personality’. The hearth predates the State, and the State assumes its natural function in defending those families that have combined to form a community,2 which is reflected as literally a ‘commonwealth’. The State intervenes when necessity dictates, but when the social organism is properly functioning, ‘paternal authority’ is not required to be subjected to State authority. The child takes its place in society as a member of a family.3 The family is the fundamental social organ from which the social organism is built. ‘The socialists, therefore, in setting aside the parent and setting up a State supervision, act against natural justice, and destroy the structure of the home’.4 It is indeed the family that one sees as the primary obstacle to the Socialist state, as much as for the ‘inclusive economy’ of the global capitalism’, both aiming at the destruction of the organic bonds through feminism, and other aberrations that have been promoted by the oligarchic Foundations and think tanks. One sees no difference between the oligarchic and Bolshevik attitude towards family bonds: both aim to replace parents with the workplace crèche.

Organic State

The organic state, literally the body politic, where a community is regarded as analogous to the human organism, is integral to the traditional ethos, which was continued by the Church from Classical times. Hence, the corpus, or body was formed as an association among trades and is along with the family unit the basis of the law of subsidiary which was developed from the Church. The corporation now assumed in popular language to be a reference to a business entity, was the corpus, the body that represented sundry interests, while the family was its own corpus, or organ of the greater social organism. The corporation flourished as the guild in the Gothic epoch. The Church as the custodian of this organic social doctrine kept the principle alive through the tumults of revolution and industrialism, and reminded states fragmented by class and hedonism of that traditional social ethos with encyclicals such as Rerum Novarum. When the aftermath of World War I accentuated the chaos of the modern world, Corporatism became a worldwide movement that challenged Capitalism and Communism for political supremacy. Church Social Doctrine was the primary inspiration, and many states embraced the Idea, as previously mentioned. Leo wrote of the organic state:

The great mistake made in regard to the matter now under consideration is to take up with the notion that class is naturally hostile to class, and that the wealthy and the working men are intended by nature to live in mutual conflict. So irrational and so false is this view that the direct contrary is the truth. Just as the symmetry of the human frame is the result of the suitable arrangement of the different parts of the body, so in a State is it ordained by nature that these two classes should dwell in harmony and agreement, so as to maintain the balance of the body politic. Each needs the other: capital cannot do without labour, nor labour without capital. Mutual agreement results in the beauty of good order, while perpetual conflict necessarily produces confusion and savage barbarity.5

The fragmentation of the organic social order – the ‘body politic’ – through class conflict and egotism, causes ‘confusion and savage barbarity’ to the extent that it is a social cancer, a social pathology, insofar as the cells and organs of the social body are at war among themselves. Capitalism and Marxism are literally social pathogens. Pope Leo specifically alludes to the social pathogens that destroy the organic state, and the need to restore tradition:

When a society is perishing, the wholesome advice to give to those who would restore it is to call it to the principles from which it sprang; for the purpose and perfection of an association is to aim at and to attain that for which it is formed, and its efforts should be put in motion and inspired by the end and object which originally gave it being. Hence, to fall away from its primal constitution implies disease; to go back to it, recovery. And this may be asserted with utmost truth both of the whole body of the commonwealth and of that class of its citizens – by far the great majority – who get their living by their labour.6

The position Leo counsels to ‘restore’ society, is fundamentally, inescapably, Rightist, in the true sense.

Leo considered it the role of the Church to act as the ‘intermediary’ in drawing ‘the rich and the working class together, by reminding each of its duties to the other, and especially of the obligations of justice’.7 It should be kept in mind that it was not the place of the Church to assume the role of a Government; hence the Church did not assume temporal authority, but was intended as the spiritual and moral authority guiding states. The Church offered ‘charity’, especially throughout the Medieval epoch, before being crushed by the Reformation and the triumph of the bourgeoisie. As for the enacting of the Social Doctrine politically, that was the responsibility of the State and of lay activists. The Church only advised in terms of what the attitude of the proprietor and the worker should be in the hope of achieving reconciliation. The spiritual impulse was expected to be the guide to right conduct.

The following duties bind the wealthy owner and the employer: not to look upon their work people as their bondsmen, but to respect in every man his dignity as a person ennobled by Christian character. They are reminded that, according to natural reason and Christian philosophy, working for gain is creditable, not shameful, to a man, since it enables him to earn an honourable livelihood; but to misuse men as though they were things in the pursuit of gain, or to value them solely for their physical powers – that is truly shameful and inhuman.8

In discussing the duty of the State in ensuring the welfare of all the citizens of the community, Leo proceeds to examine this in the context of society as an organism:

There is another and deeper consideration which must not be lost sight of. As regards the State, the interests of all, whether high or low, are equal. The members of the working classes are citizens by nature and by the same right as the rich; they are real parts, living the life which makes up, through the family, the body of the commonwealth; and it need hardly be said that they are in every city very largely in the majority. It would be irrational to neglect one portion of the citizens and favour another, and therefore the public administration must duly and solicitously provide for the welfare and the comfort of the working classes; otherwise, that law of justice will be violated which ordains that each man shall have his due. To cite the wise words of St. Thomas Aquinas: ‘As the part and the whole are in a certain sense identical, so that which belongs to the whole in a sense belongs to the part.’ Among the many and grave duties of rulers who would do their best for the people, the first and chief is to act with strict justice – with that justice which is called distributive – toward each and every class alike.9

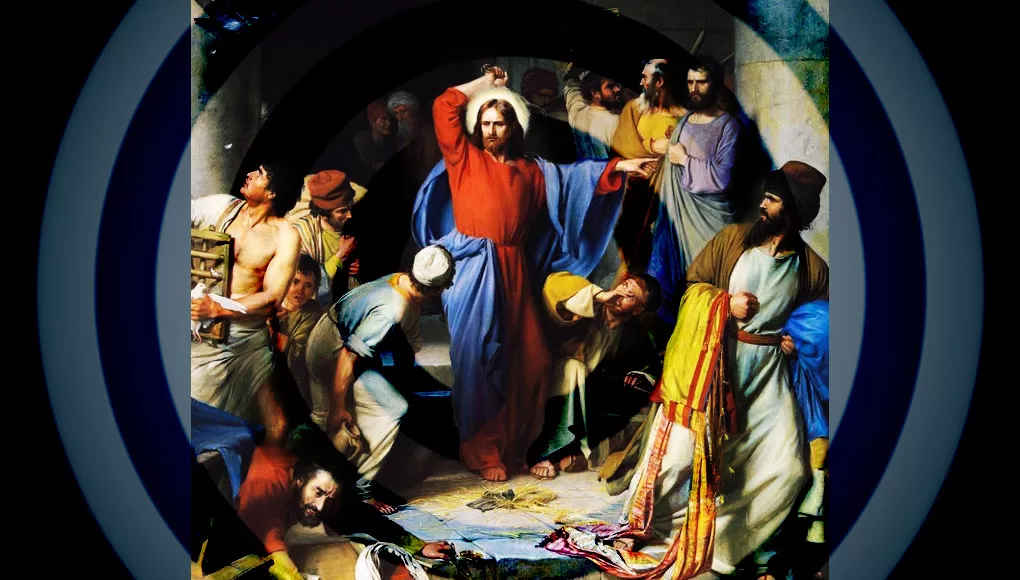

Leo draws on Church lore in showing how the organic state is part of the traditional legacy of the Church. Indeed, it can be seen in the Bible where the early Church is described as an organism, the Body of Christ:

For the body is not one member, but many. If the foot says, ‘Because I am not a hand, I am not a part of the body,’ it is not for this reason any the less a part of the body. And if the ear says, ‘Because I am not an eye, I am not a part of the body,’ it is not for this reason any the less a part of the body. If the whole body were an eye, where would the hearing be? If the whole were hearing, where would the sense of smell be? But now God has placed the members, each one of them, in the body, just as He desired. If they were all one member, where would the body be? But now there are many members, but one body. And the eye cannot say to the hand, ‘I have no need of you’; or again the head to the feet, ‘I have no need of you.’ On the contrary, it is much truer that the members of the body which seem to be weaker are necessary; and those members of the body which we deem less honourable, on these we bestow more abundant honour, and our less presentable members become much more presentable, whereas our more presentable members have no need of it. But God has so composed the body, giving more abundant honour to that member which lacked, so that there may be no division in the body, but that the members may have the same care for one another. And if one member suffers, all the members suffer with it; if one member is honoured, all the members rejoice with it.10

‘No matter what changes may occur in forms of government, there will ever be differences and inequalities of condition in the State’, Leo wrote, thus rejecting the impersonality of liberal egalitarianism. 11 The state needs to ensure however that no component of it is deprived. This is really a matter of organic health, for it does not profit the social organism, like any organism, when one part of it is withering. If the cells or organs of any organism are in ill-health then the whole organism suffers and might die. Leo explains the duty of the State toward the well-being of the constituent parts:

[I]t is the business of a well-constituted body politic to see to the provision of those material and external helps ‘the use of which is necessary to virtuous action.’12 Now, for the provision of such commodities, the labour of the working class – the exercise of their skill, and the employment of their strength, in the cultivation of the land, and in the workshops of trade – is especially responsible and quite indispensable. Indeed, their co-operation is in this respect so important that it may be truly said that it is only by the labour of working men that States grow rich. Justice, therefore, demands that the interests of the working classes should be carefully watched over by the administration, so that they who contribute so largely to the advantage of the community may themselves share in the benefits which they create – that being housed, clothed, and bodily fit, they may find their life less hard and more endurable.13Whenever the general interest or any particular class suffers, or is threatened with harm, which can in no other way be met or prevented, the public authority must step in to deal with it. … The limits must be determined by the nature of the occasion which calls for the law’s interference – the principle being that the law must not undertake more, nor proceed further, than is required for the remedy of the evil or the removal of the mischief.14

It is interesting to note that Leo appealed to patriotism towards one’s homeland as an element in ensuring the health of its constituents, ‘that the members of the commonwealth should grow up to man’s estate strong and robust, and capable, if need be, of guarding and defending their country’.15

Socialism aims to eliminate all but the hands from the social organism; Classical Liberalism, all but the head. Both aim to dismember the social organism in favour of the supremacy of one component. Leo while primarily addressing the needs of the working class, nonetheless rejected the notion of ‘equality’; that had manifested as a bloody, hellish slogan since the French Revolution, proceeded by socialism, and bloodier still under Bolshevism thirty years later. It was private property that needed distributing, not eliminating, and no solution was to be found in coveting what rightly belonged to others by appropriation in the name of ‘equality’. It is a reminder that the greed of the bourgeois can be just as manifest in the proletarian:

Most of all it is essential, where the passion of greed is so strong, to keep the populace within the line of duty; for, if all may justly strive to better their condition, neither justice nor the common good allows any individual to seize upon that which belongs to another, or, under the futile and shallow pretext of equality, to lay violent hands on other people’s possessions.16

Notable however is also this comment: ‘[I]f all may justly strive to better their condition’. Rerum Novarum is not an apologia for capitalist exploitation; it is the answer to it, of more value than Das Kapital, The Communist Manifesto, or the works of Lenin or Trotsky. Leo, when addressing strikes and the increasing violence of the labour movement, as injurious to both proprietors, the trades and the social order, clearly stated that the causes are most likely to rest with social injustice and that these must be addressed a priori: ‘The laws should forestall and prevent such troubles from arising; they should lend their influence and authority to the removal in good time of the causes which lead to conflicts between employers and employed’.17 Human beings should not be used as ‘mere instruments for money-making. It is neither just nor human so to grind men down with excessive labour as to stupefy their minds and wear out their bodies.’18

While the individual personality and the family are the building blocks of the social organism that should not be imposed upon unnecessarily, the State maintains the authority to intervene when there is a social pathogen.

Rulers should, nevertheless, anxiously safeguard the community and all its members; the community, because the conservation thereof is so emphatically the business of the supreme power, that the safety of the commonwealth is not only the first law, but it is a government’s whole reason of existence; and the members, because both philosophy and the Gospel concur in laying down that the object of the government of the State should be, not the advantage of the ruler, but the benefit of those over whom he is placed.19

Work was ordained by God according to the Christian ethos, and is part of the universal condition of the human creation. Whether work is undertaken menially or mentally it is still part of the same divine order. The proprietor had a duty to be ever-mindful of this.

His great and principal duty is to give every one what is just. Doubtless, before deciding whether wages are fair, many things have to be considered; but wealthy owners and all masters of labour should be mindful of this – that to exercise pressure upon the indigent and the destitute for the sake of gain, and to gather one’s profit out of the need of another, is condemned by all laws, human and divine. To defraud any one of wages that are his due is a great crime which cries to the avenging anger of Heaven.20

The earnings of the labourer are ‘sacred’ and must not be confiscated by unreasonable means, including usury. ‘Lastly, the rich must religiously refrain from cutting down the workmen’s earnings, whether by force, by fraud, or by usurious dealing’.21

Usury

It was the Church that led the fight against usury until Reformation eminences gave it scriptural justification and turned traditional Social Doctrine on its head, in favour of capitalism. The 12th Canon of the First Council of Carthage (345) and the 36th Canon of the Council of Aix (789) declared usury reprehensible. The Third Council of the Lateran (1179) and the Second Council of Lyons (1274 condemned usurers. The Council of Vienne (1311) declared the defence of usury a heresy.

The Church teachings on usury (defined as a loan bearing any interest) were codified in an encyclical in 1745 by Benedict XIV, after consulting with many knowledgeable Churchmen.22 The first principle of the encyclical is:

The nature of the sin called usury has its proper place and origin in a loan contract. This financial contract between consenting parties demands, by its very nature, that one return to another only as much as he has received. The sin rests on the fact that sometimes the creditor desires more than he has given. Therefore he contends some gain is owed him beyond that which he loaned, but any gain which exceeds the amount he gave is illicit and usurious.23

Naturally, it would be regarded today as a joke at best if one were expected to make a loan without interest. But then the joke is on those in debt, individuals, families, communities, nations, the world. And it becomes a perverse joke when there is destitution and even starvation, although the production of food and other essentials of life are abundant. It is the phenomenon called ‘poverty amidst plenty’. During the Great Depression, while masses went hungry, governments across the world ordered farmers to destroy crops and livestock to maintain price levels. John Hargreave, leader of the Depression-era Greenshirts for Social Credit, drawing on newspaper reports, listed dozens of occasions when produce was destroyed by State decree.24 It is this situation for which Father Coughlin demanded a remedy, and one which was not forthcoming from the much acclaimed New Deal until the USA went into a war-economy. Father Denis Fahey wrote extensively about the banking system.25

Whether secular authorities upheld the Church doctrines on usury was another matter, and there were many ways to circumvent the Canonical teachings.26 With the Reformation the ‘modern’ conception of banking arose, where usury was described as a ‘progressive’ form of commerce, and money-lending was upheld as a ‘service’, as argued by the French jurist Molinaeus in his 16th century Treatise on Contracts & Usury, a book that the Church tried to ban. In England Jeremy Bentham wrote A Defence of Usury, while other economic theorists such as Ricardo and John Stuart Mill stated there should be no limits on contracting parties.27

Property as a Social Function

The question that Social Doctrine asks of private property is: to what use is it put? This also includes the use of money; hence the matter of usury:

The chief and most excellent rule for the right use of money is one the heathen philosophers hinted at, but which the Church has traced out clearly, and has not only made known to men’s minds, but has impressed upon their lives. It rests on the principle that it is one thing to have a right to the possession of money and another to have a right to use money as one wills. Private ownership, as we have seen, is the natural right of man, and to exercise that right, especially as members of society, is not only lawful, but absolutely necessary. ‘It is lawful,’ says St. Thomas Aquinas, ‘for a man to hold private property; and it is also necessary for the carrying on of human existence.’ ‘But if the question be asked: How must one’s possessions be used? – the Church replies without hesitation in the words of the same holy Doctor: ‘Man should not consider his material possessions as his own, but as common to all, so as to share them without hesitation when others are in need’.28

The Social Doctrine does not require giving until one’s family is destitute, but maintains that once the needs of the family are well cared for, the excess should be distributed rather than accumulated.29 The Social Doctrine is then anti-Capitalist, yet upholds the ‘sanctity’ of private property. Pius XI in Quadragesimo Anno commented:

Property, that is, ‘capital,’ has undoubtedly long been able to appropriate too much to itself. Whatever was produced, whatever returns accrued, capital claimed for itself, hardly leaving to the worker enough to restore and renew his strength. For the doctrine was preached that all accumulation of capital falls by an absolutely insuperable economic law to the rich, and that by the same law the workers are given over and bound to perpetual want, to the scantiest of livelihoods. It is true, indeed, that things have not always and everywhere corresponded with this sort of teaching of the so-called Manchesterian Liberals; yet it cannot be denied that economic social institutions have moved steadily in that direction.30

Social Doctrine repudiates the accumulation of capital whereby oligarchic wealth in perpetuated and ceases to have a social function. The answer of Socialism, is an ‘equally fictitious moral principle that all products and profits, save only enough to repair and renew capital, belong by very right to the workers’.31 The third option is again the wider distribution of capital:

[T]he riches that economic-social developments constantly increase ought to be so distributed among individual persons and classes that the common advantage of all, which Leo XIII had praised, will be safeguarded; in other words, that the common good of all society will be kept inviolate.32

One might hope that since 1891, or 1931, a lot more about economic function had been learnt. Yet no economic proposition like the raising of the minimum wage causes such an outcry of hardship from employers, other than the outcry from both employers and employees when there is a suggestion that welfare benefits be raised in accord with rising costs of living. If production is not consumed, then it is pointless, and this cannot be done with insufficient purchasing power. The Socialist answers: raise taxes. Again, the problem of production and consumption and the lack of purchasing power, the problem of distribution, is not solved. Pius XI advocated profit-sharing, which has not only a material, but a moral-ethical purpose:

To each, therefore, must be given his own share of goods, and the distribution of created goods, which, as every discerning person knows, is labouring today under the gravest evils due to the huge disparity between the few exceedingly rich and the unnumbered propertyless, must be effectively called back to and brought into conformity with the norms of the common good, that is, social justice.33

To this could be added the Social Credit formulae of a National Dividend, given to every man, woman and child as a shareholder in a ‘common-wealth’, making up the shortfall in purchasing power (Social Credit’s A+B Theorem)34 inherent in the system. It is in this manner that the problem of capital accumulation can be solved while not only maintaining but increasing private property. It is why many Catholics such as the Pilgrims of Saint Michael were inspired by Social Credit, and priests such as Denis Fahey and Coughlin sought similar ways to eliminate usury from the banking system.

References

1Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum (12).

2Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum (13).

3Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum (14).

4Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum (14).

5Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum (19).

6Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum (27).

7Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum (19).

8Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum (20).

9Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum (33).

10I Corinthians, 12: 14-26

11Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum (34).

12Thomas Aquinas, ‘On the Governance of Rulers’, 1, 15 (Opera omnia, ed. Vives, Vol. 27, p. 356); cited by Leo.

13Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum (34).

14Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum (36).

15Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum (36).

16Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum (38).

17Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum (39).

18Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum (42).

19Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum (35).

20Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum (20).

21Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum (20).

22Benedict XIV, Vix Pervenit, ‘On Usury & Other Dishonest Profits (1745).

23Benedict XIV, Vix Pervenit, (1).

24See: Bolton, Opposing the Money Lenders, (London: Black House Publishing, 2016), pp. 102-104.

25Denis Fahey, The Mystical Body of Christ & the Reorganisation of Society (Cork: The Forum press, 1945), passim.

26K. R. Bolton, The Banking Swindle (London: Black House Publishing, 2013), p. 76.

27Bolton, Opposing the Money Lenders, p. 4.

28Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum (22).

29Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum, ibid.

30Pius XI, Quadragesimo Anno (54).

31Pius XI, Quadragesimo Anno (55).

32Pius XI, Quadragesimo Anno (57).

33Pius XI, Quadragesimo Anno (58).

34This mystic Theorem is actually quite rudimentary. Dr. Oliver Heydorn, a Catholic and one of today’s most cogent exponents of Social Credit explains: A = All payments made to individuals (wages, salaries, and dividends); B = All payments made to other organisations (raw materials, bank charges, and other external costs). ‘Now the rate flow of purchasing power to individuals is represented by A, but since all payments go into prices, the rate of flow of prices cannot be less than A plus B. Since A will not purchase A plus B, a proportion of the product at least equivalent to B must be distributed in the form of purchasing power [National Dividend] which is not comprised in the description grouped under A’. Oliver Heydorn, Social Credit Economics (Ancaster, Ontario, Canada. 2014), p. 149.