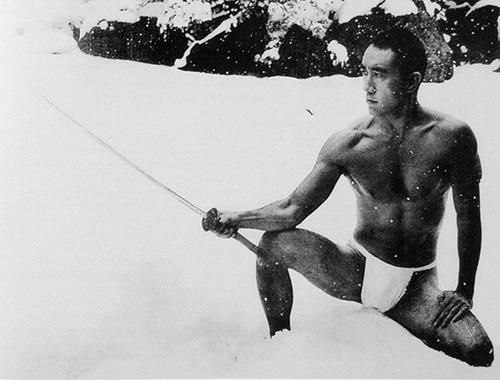

Let us continue the reasoning started in my previous article for Arktos Journal based on the discussion by the Japanese writer Yukio Mishima (1925–1970) of the classic samurai treatise Hagakure (‘Hidden by the Leaves’) (葉隱) in the 1967 essay ‘Hagakure nyūmon’ (‘My Hagakure’) (葉隠入門), in which Mishima identifies three key philosophical intentions of Hagakure — the philosophy of love, the philosophy of action and the philosophy of life and death.

Having paid sufficient attention to the philosophy of love, let us focus the present discussion on the philosophy of action. Starting the discussion about this in his essay, Mishima points out that the philosophy of Hagakure is a philosophy of absolute subjectivity that overcomes any objectivity: ‘As a philosophy of action, Hagakure values subjectivity. It considers action to be a function of the subject and sees death as the outcome of the action. The philosophy of Hagakure offers a standard of action, which is an effective means of overcoming the limitations of personality and subjugating oneself to something greater. However, nothing could be further from Hagakure than Machiavelli’s philosophy in which a person freely combines element A with element B, or force A with force B. Jōchō’s philosophy is highly subjective: there are no objects in it. This is a philosophy of action, not a combination of different elements or forces.’

The total subjectivity of the individual, assumed by Hagakure within the framework of what Mishima calls the philosophy of action, is interpreted by the Japanese writer in terms of faith, preparation and determination. He quotes the following saying of Jōchō from the first book of Hagakure:

Among the scrolls hanging on Naoshige-sama’s wall was a scroll with the words: “Important matters should be treated lightly.” Upon seeing this scroll, Master Ittei added, “Non-essential matters should be taken seriously.” Among human affairs, no more than one or two can be called important. They can be understood if you think about them throughout the day. It’s about thinking about your affairs in advance and then dealing with them easily when the time comes. Dealing with an event is difficult if you haven’t thought about it before, because you can never be sure that you will succeed. If you think about everything in advance, you will be guided by the principle: “Important things should be treated lightly.”

Mishima gives the following comment to this testament of samurai wisdom:

Faith is determination. Determination must be tested daily for many years. Obviously, Jōchō makes a distinction between “great faith” and “small faith”. In other words, a person must deeply feel the foundations of his faith in order to act effortlessly and spontaneously at the moment of making a decision. A “small faith” is a system of views on the trivia of everyday existence.

Prosper Mérimée (French writer, historian and philologist of the 19th century) once remarked:

In fiction, not a single detail appears by chance. Even a casually mentioned glove plays an important role.’ This is not only true of novels. When we live and enjoy life, we look at the smallest details, reason and draw conclusions. Otherwise, the foundation of our lives will be destroyed and even our “great faith” will be questioned.

So, when the Englishmen drink tea, the pourer always asks each person what to pour first, milk or tea. From the outside, it may seem that it does not matter at all, because in the end it still turns out to be tea with milk. However, this little thing clearly reveals the character of a person: some Englishmen are convinced that first you need to pour milk and then tea, while others prefer to pour tea first and then milk. Therefore, if the pourer does not take into account the opinion of a particular person, the latter may see this as a violation of his global principles.

When Jōchō says that ‘important things should be taken lightly’, he means that a tiny ant hole can destroy a huge dam. Therefore, a person should pay great attention to his daily beliefs, his ‘small faith’. This is a good lesson for our troubled times, when people value only ideology and do not take into account the trivia of everyday life.

Thus, the Hagakure philosophy of action presupposes total awareness and no less total control over oneself and one’s manifestations — not only in deeds, but also in thoughts and intentions. What Mishima calls ‘small faith’ — the familiar aspects of our daily lives that may seem insignificant but form the foundation for our inner stability, which is the key to future victories and achievements.

This is inextricably linked to the aspect of subjectivity that we are talking about — because only a harmonious person can be his own measure, his own core and foundation, and, accordingly, an absolute subject. Harmony, in turn, is unthinkable without the components of ‘small faith’ that shape our life world. At the same time, the ‘small faith’ is only a prerequisite for stable and unshakeable adherence to the principles of the ‘great faith’, to which the action of the absolute subject should be directed, which, in turn, should be ready to show total determination. Hagakure claims:

The basic principle that a person should be devoted to day after day is that one must die in accordance with the Way of the Samurai. The Way of the Samurai is first of all the understanding that you do not know what may happen to you in the next moment. Therefore, you need to think about every unforeseen opportunity day and night. Victory and defeat often depend on fleeting circumstances. But in any case, it is not difficult to avoid shame — it is enough to die. You need to achieve your goal even if you know that you are doomed to defeat. Neither wisdom nor technique is needed for this. A true samurai does not think about victory and defeat. He fearlessly rushes towards the inevitable death. If you do the same, you will awake from a dream.

Mishima comments on this saying of Jōchō:

A person can make a decision quickly because he has been preparing for this for a long time. He can always choose a course of action, but he cannot choose the time. The moment of decisive action looms in the distance for a long time, and then suddenly approaches. Isn’t life, in this case, a preparation for these decisive actions, which, perhaps, fate has prepared for a person? Jōchō stresses the importance of acting without delay when the time is right.

‘The action without delay’ that Mishima writes about is an extremely significant aspect of Hagakure’s philosophy of action. At the same time, we are not talking about recklessness, which the Japanese writer emphasises — because when you live consciously, you constantly prepare your heart and mind for a variety of possible circumstances. When these circumstances occur (regardless of their nature), you can act as quickly as possible, because nothing can surprise you.

In addition to aspects related to careful control of one’s inner state, a plan of action in accordance with the guidelines of the ‘great and small faiths’, the philosophy of action of Hagakure also assumes actions of a different kind, as stated in the following quote by Mishima:

Fifty or sixty years ago, every morning samurai washed, shaved their forehead, they smeared their hair with lotion, cut their nails and toenails, rubbed their hands and feet with pumice stone, and then with wood sorrel, and generally did everything to have a neat appearance. It goes without saying that they also paid special attention to weapons: they were wiped, polished and stored in exemplary order.

Although it may seem that careful self-care betrays posturing and panache in a person, this is not the case. Even if you know that you may be struck down on this very day, you must meet your death with dignity, and for this you need to take care of your appearance. After all, your enemies will despise you if you look sloppy. Therefore, they say that both old and young people should constantly take care of themselves.

Although you say it is difficult and time-consuming, the calling of a samurai requires this sacrifice. In fact, it is not difficult and does not take much time. If you strengthen your resolve to fall in a conflict every day and live as if you are already dead, you will achieve success in deeds and in battle, and you will never disgrace yourself. Meanwhile, anyone who does not think about it day and night, who lives indulging his desires and weaknesses, sooner or later brings shame upon himself. And if he lives for his own pleasure and thinks that this will never happen, his lecherous and ignorant actions will cause a lot of trouble.

Anyone who has not decided in advance to accept the inevitable death, tries in every possible way to prevent it. But if he was ready to die, wouldn’t he become flawless? In this case, you need to think about everything and make the right decision.

This hides an important aspect of the wisdom of Hagakure, which, by the way, Mishima himself followed throughout his life. The duality between taking systematic and careful care of oneself and one’s own beauty and willingness to die at any moment is completely artificial. External perfection and a system of regular actions aimed at achieving it are necessary for a person both for internal balance (one of the systems of ‘small faith’) and so that the moment that will be the last one can fall like a beautiful Sakura blossom petal, having astonished even the enemies. Perfection in the way of the Hagakure philosophy of action has not only an internal but also an equally important external aspect.

The external aspect of the Hagakure philosophy of action manifests itself, of course, not only in visual perfection. The key here is the relationship between beliefs, words and, most importantly, deeds — that is, what people see in us. Commenting on this, Mishima writes,

A common mistake of our days is the belief that words and deeds are manifestations of conscience and philosophy, which in turn are products of the mind, or heart. However, we are mistaken when we believe in the existence of a heart, conscience, reason, or abstract ideas. So, for people like the Ancient Greeks, who believed only in what they could see with their own eyes, this invisible mind, or heart, did not exist at all.

Thus, in order to deal with such an indefinite entity as the mind or the heart, a person must judge only by external manifestations, such as words and actions. Only then will he be able to understand where this essence came from… Any minor oversight in word or deed can destroy our entire philosophy of life. This harsh truth is not easy to accept. If we believe in the existence of the heart and want to protect it, we must watch everything we say and do. This is how we can cultivate a strong inner passion and delve into the unattainable depths of our nature.

Such a worldview, being extremely resource-intensive for an individual, holding it in the background of his own consciousness, is equally extremely energy-consuming. In other words, it is a life of constant tension, from which it is impossible to retreat. Mishima comments on this as follows:

If, in the name of moral goals, a person strives to live beautifully, and if he considers death to be the final standard of this beauty, life becomes a constant strain for him. Jōchō, for whom laziness is the highest evil, indicates the need to exist in tension, which does not weaken for a moment. Such is the struggle with the circumstances of everyday life. This is the calling of a samurai.

To a Westerner, such a life may seem like an endless self-torture. But, like everything else in samurai ethics, this aspect has another side. Its secret lies in always living ‘in the present moment’, as Mishima points out, quoting the following statement of the Hagakure:

Truly, there is nothing but the true purpose of the present moment. A person’s whole life is a sequence of moments. If a person fully understands the present moment, he does not need to do anything else and has nothing to strive for. Live and stay true to the true purpose of the present moment. People tend to omit the present moment, and then look for it, as if it is somewhere far away. But no one seems to notice this. However, if a person is deeply aware of this, he must, without delay, move from one experience to another. Someone who has once comprehended this can forget about it, but he has already changed and has become different from everyone else. If a person fully understands what it means to live in the present moment, he will have almost no worries.

Thus, constant internal tension, when adopting the Hagakure philosophy of action, ceases to be perceived as tension. This is a special inner state, akin to the steadfastness of Julius Evola’s ‘absolute individual’, for whom everything is thought out at the same time and the potential for total spontaneity is preserved; there is a readiness to die at any moment, but at the same time there is an openness to life and concentration on the purpose and meaning of the present moment; self-care to the smallest detail gets along with indifference to victory and defeat, successes and failures, and as a result — to the very consequences of life. The paradox that Mishima highlights in “Hagakure nyūmon” is that such an attitude to life, its many details and aspects, leads to the most productive and harmonious individual existence. In other words, an icy willingness to die is the key to a successful life. This paradox will be revealed in more detail in our next article for Arktos Journal, dedicated to the Hagakure philosophy of life and death, as explained by Yukio Mishima.